What It's Like To Be A Worm

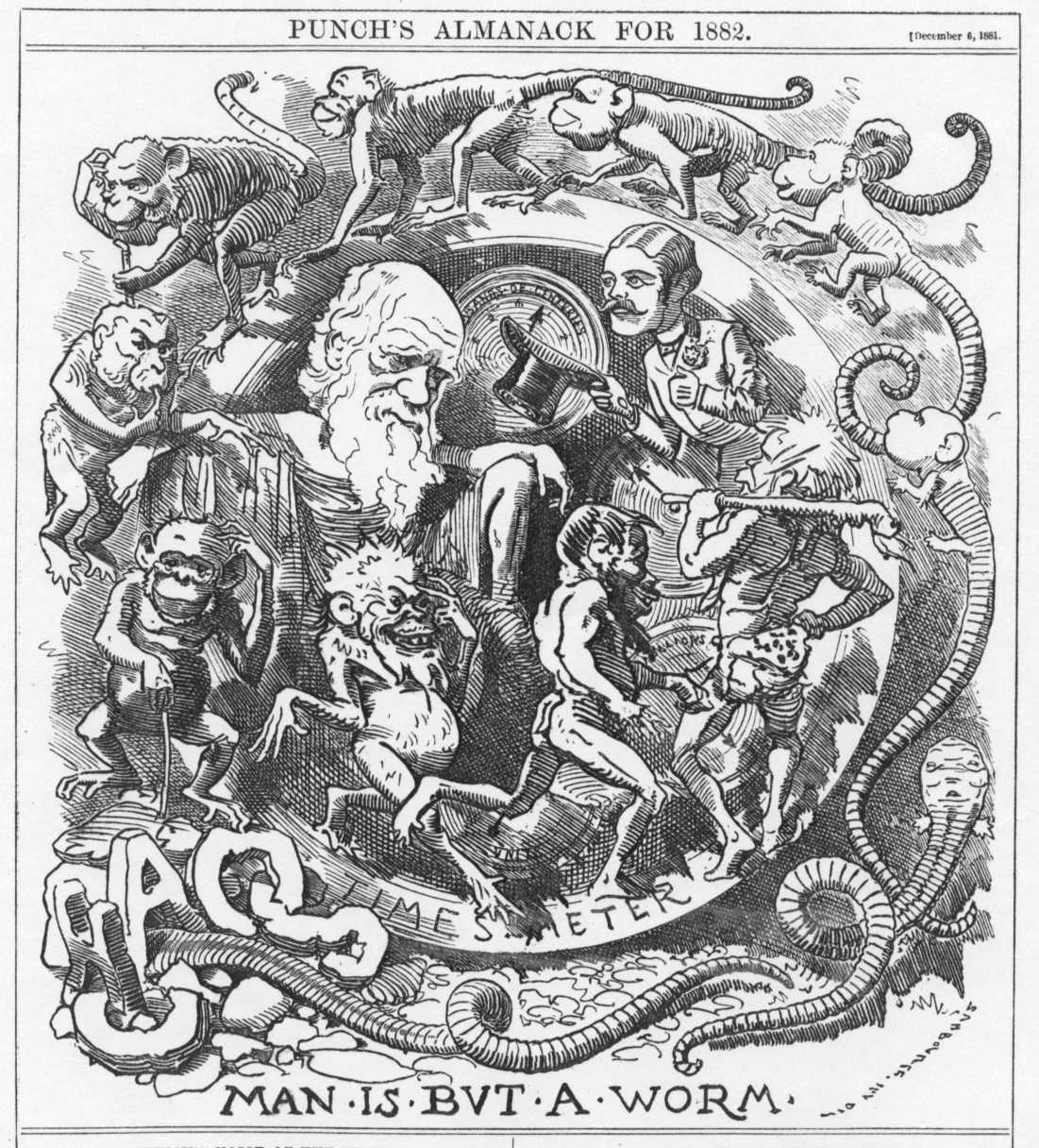

On 1 November 1837, Charles Darwin delivered a talk to the Geological Society of London on the role of earthworms in soil formation. The Society is said to have expected something grander from the celebrated scientist, but Darwin was already deeply fascinated by worms. Indeed, his interest intensified throughout his life and served as the subject of his final book, The Formation of Vegetable Mould Through the Action of Worms, published in 1881.

Darwin’s book is noteworthy not just as the first major text on bioturbation (the reworking of soils by organisms) but also for how he approaches the inner lives of earthworms:

"Judging by their eagerness for certain kinds of food, they must enjoy the pleasure of eating. Their sexual passion is strong enough to overcome for a time their dread of light … Although worms are so remarkably deficient in the several sense-organs, this does not necessarily preclude intelligence … and we have seen that when their attention is engaged, they neglect impressions to which they would otherwise have attended; and attention indicates the presence of a mind of some kind."

Darwin was not the first scientist to reflect on animal sentience, that is, their capacity for pain and pleasure. Aristotle wrote extensively on the topic, observing, for instance, that “bees seem to take pleasure in listening to a rattling noise” and that “the tunny delights more than any other fish in the heat and sun.”

Until the nineteenth century, such observations remained anecdotal. Darwin was among the first to ground judgements about animal sentience on careful experiments, such as suspending pieces of raw and roasted meat over the worms’ habitat overnight to see which they preferred.1

Even more striking than Darwin’s methodological approach to studying sentience was his choice of earthworms for his subject. Such a selection in place of a human subject made Darwin a forerunner of a research program that has recently gained incredible momentum: the science of borderline sentience. That is, the investigation of sentience in creatures that dwell near the boundary between sentience and non-sentience.

Whereas Darwin’s interest in the inner workings of the worm mind was driven by pure curiosity, researchers today study borderline sentience to avoid causing gratuitous suffering in contexts such as agriculture and research. In the UK, octopuses and decapod crustaceans have been recognized as “sentient” since 2021, meaning government ministers legally must consider their welfare in future policies. This has just resulted in a ban on the practice of boiling crabs and lobsters alive.

The same considerations also apply to humans. Every year, around 400,000 people fall into “prolonged disorders of consciousness,” such as a coma, due to injury or illness.2 While no longer recognizably sentient, as many as a quarter of these patients are thought to retain some awareness. The better we understand borderline sentience, then, the better we will be able to care for (and perhaps even cure) such individuals.

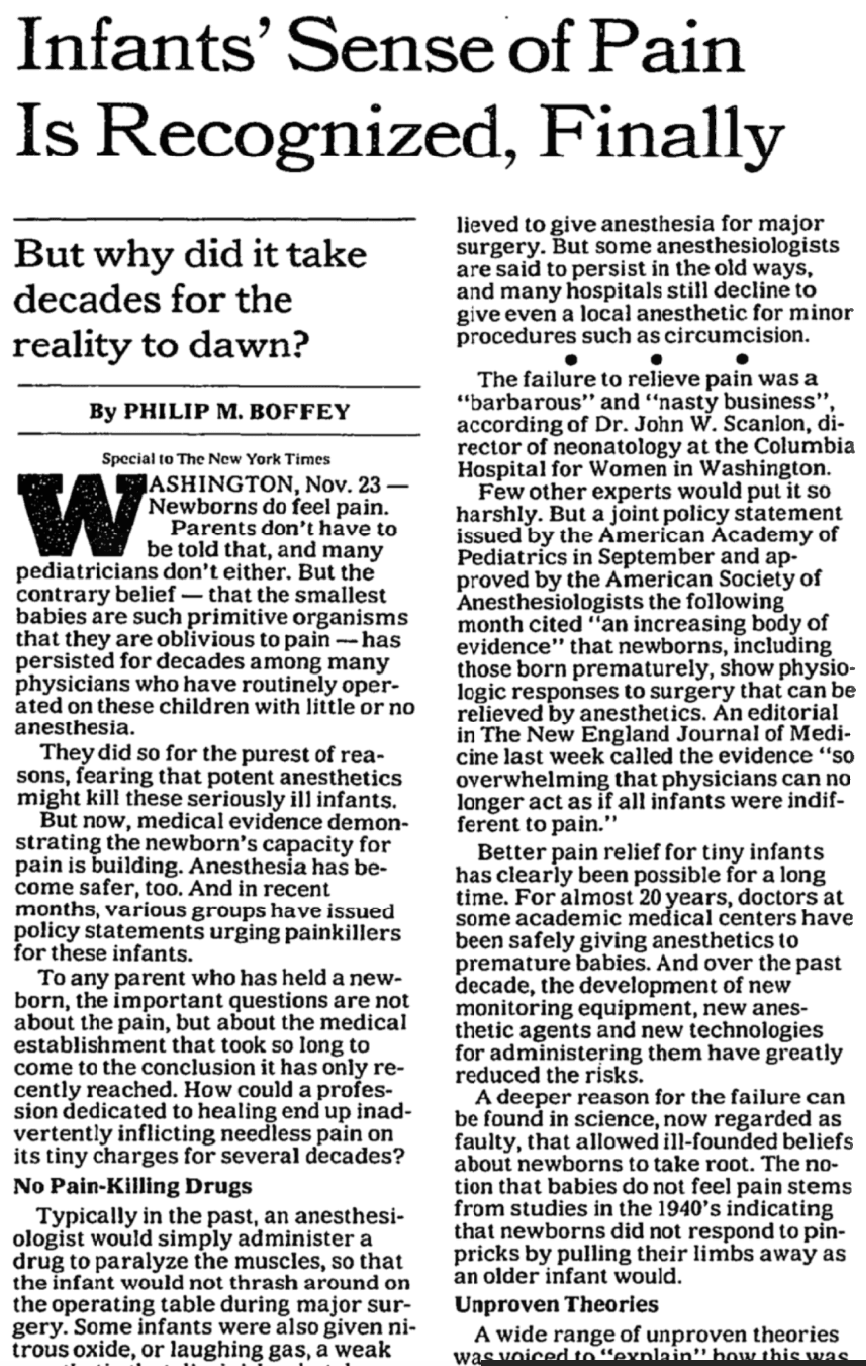

Indeed, misjudgments about sentience can have grave consequences. Before the 1980s, it was common practice to perform surgery on newborns without anaesthesia, partly due to the assumption that neonates do not experience meaningful pain. This changed in 1987, driven by mounting physiological evidence (such as electrical activity in the cortex, sharp increases in stress hormones in blood samples, and the microscopic structures of developmental brain tissues) of the capacity for pain sensation in infant brains, alongside campaigns by mothers whose children were subjected to such treatment.3

Fortunately, rapid advances in neurophysiology are allowing us to make judgments about borderline sentience that would have seemed impossible a few years ago. Tools like high-resolution functional MRI (fMRI), calcium imaging, and high-density electrode arrays can now help us observe detailed neural activity in real time and correlate specific patterns with conscious states. The field of connectomics, which attempts to map the complete wiring diagram of neural systems, also promises to reveal the fine-grained physical processes underlying sentience in humans and other creatures.

Studies of the microscopic worm C. elegans, with its fully mapped and readily accessible nervous system, have become ideal test cases for assessing theories of sentience against detailed physiological data. The hope is that discoveries made with this species will help refine how we assess sentience in humans, other complex animals, and even artificial neural networks.

{{signup}}

Borderline Sentience

While sentience is often defined as “the capacity for pain and pleasure,” this definition isn’t complete. Sentience, in the sense we are using the term, is a combination of two things: consciousness and valence. To say an organism is conscious means that there is “something it is like to be that organism”; that it experiences the world from its own subjective point of view. That is how philosopher Thomas Nagel puts it in his famous paper, “What is it Like to be a Bat?”4

“Valence” is short for “hedonic valence,” from “hedone,” the Greek word for “pleasure.” To say that a conscious experience is valenced is to say that it is pleasant or unpleasant, that it feels good or feels bad. Toothache, breathlessness, and nausea are examples of negatively valenced experiences, whereas things like euphoria, flow state, and the sensation of quenching one’s thirst are all examples of positively valenced experiences.5

Not all conscious experiences have significant valence, however. The visual experience of seeing a brick wall, for instance, may feel neither good nor bad. Some scientists have even suggested that there may be conscious creatures that lack valenced experience. For example, Simona Ginsburg and Eva Jablonka speculate that certain ancient animals, such as jellyfish, might experience a meaningless “white-noise sensation”— an inner buzzing and crackling arising as a side-effect of their decentralized nervous systems.

Valenced experience, if and when it does exist, however, has tremendous practical importance. This is because many (some would say all) practical decisions are ultimately about increasing positive experiences and decreasing negative ones. When we decide whether to go on holiday in England or the Galápagos, we choose the place we expect to enjoy most. When we arrive at the ward where our Grandma has been hospitalized, we are concerned about whether she is comfortable and free from distress. And when we decide whether to permit scientists to inflict spinal injuries on rats to test a neural regeneration drug, we weigh the potential value of this work against the suffering it will cause the test animals.

Sentience, then, is the combination of subjective experience and the capacity to evaluate sensation as good or bad.

While this might sound deceptively simple, sentience poses formidable challenges to scientists because there is a vast range of questionable, borderline cases. Examples include humans (such as those with brain injuries), non-human animals (such as insects or fish), and some creatures that are neither humans nor animals (such as neural organoids and AI).

Representatives of the first category include people with prolonged disorders of consciousness and those in early developmental stages. Before the 1970s, patients with disorders of consciousness were frequently grouped together as “non-responsive” or “comatose.” In 1972, physician-scientists Bryan Jennett and Fred Plum established the diagnostic category persistent vegetative state for unresponsive patients who exhibit sleep-wake cycles and “autonomic” functions such as respiration, digestion, and pupil dilation, though they are traditionally thought to lack awareness.6

Human babies are another example. Here, research on developmental phases has led us to abandon the assumption that newborn infants lack significant sentience and replace it with an understanding of the neural processes thought to underlie experiences of pain and pleasure starting at 12 weeks’ gestation. When, exactly, sentience arises is still up for debate (partly because of disagreement about whether sentience in humans rests essentially on activity in the cortex), but it has similarly enormous implications.7

When it comes to non-human animals, views about which creatures are sentient diverge even more. At one extreme are those held by the neuroscientist Edmund Rolls, who attributes sentience only to organisms with distinctively primate neural mechanisms, the granular prefrontal cortex in particular. At the other end are those held by cognitive psychologist Arthur Reber, who argues that even single-celled organisms such as bacteria may be sentient. Most scientists fall somewhere in the middle. There is a broad consensus that mammals, birds, and octopuses are sentient, and that single-celled organisms are not, but considerable disagreement beyond these cases.

The last category of borderline-sentience is non-human non-animals, such as human neural organoids and deep neural networks.8 A human neural organoid is a lab-grown tissue derived from human stem cells grown in a culture that allows them to differentiate into various neural cell types that mimic those of the brain.

Neural organoids offer great potential for advancing neuroscientific research without the need for invasive experimentation on humans or other animals. At the same time, the pioneer of “neuroethics,” Andrea Lavazza, has expressed concern that in growing something like a portion of human brain tissue, we might unwittingly be creating something like a portion of human mind, capable of positive and negative experience.

Deep neural networks fall into a similar category. These are the kind of computer architectures that underlie all the recent advances in artificial intelligence, from video generation to chatbots. Like organoids, they are inspired by the structure of the nervous system and are thought to have some analogous functions.

A group led by Patrick Butlin and Robert Long argues that existing deep neural networks satisfy some nontrivial indicators associated with influential (though contested) computational theories of consciousness. For example, the transformer networks that drive chatbots have some of the features proposed by the “global workspace theory,” according to which conscious states arise when information is broadcast across a system so that many specialized processes can access and use it.9

Butlin and Long’s “indicators” for consciousness drive at something extremely important for machine consciousness, animals, and humans alike: the question of how we can know sentience when we see it.

The Limits of Behavioral Evidence

Conscious experiences are private in the sense that they are not directly observable from the outside. When it comes to healthy adult humans, this does not pose too great a problem. If a research psychologist wants to know what a patient is experiencing, they can ask. It would be handy if we could do the same with earthworms, but regrettably, they can’t speak. The same is true for comatose humans and neural organoids. And while we can ask a chatbot or a parrot what it’s experiencing, their answers are of little use as evidence, given that they have been trained to produce human-like responses without necessarily possessing the underlying subjective experiences those responses typically indicate.10

This all goes to say that studying borderline sentience forces researchers to seek out and validate markers of sentience other than the subjects’ verbal report.

The most frequently substituted markers are non-verbal behaviors.11 These range from comparatively simple things, such as avoiding harm or guarding an injury (e.g., pulling an injured paw near a body), to more sophisticated behaviors such as self-administering painkillers or making motivational trade-offs (for example, the way in which worms, according to Darwin, experience sexual desire strongly enough to overcome their dislike of light). Indeed, in the mid-twentieth century, radical “behaviorists” led by B. F. Skinner held that all of psychology could, in principle, be explained in terms of observable behavior.

Behavioral markers of sentience are frequently unsatisfactory, however, as sentient creatures may fail to exhibit the usual behavioral signs for a variety of reasons. Someone with cognitive motor dissociation, for example, can have a substantial inner life without exhibiting any outward signs of it.

This is what happened to Kate Bainbridge, a 26-year-old woman who lost responsiveness due to inflammation of the brain and spine, triggered by a viral infection. Although she was diagnosed as being in a persistent vegetative state, she later regained the ability to communicate via keyboard. When she did, she reported that she had remained aware, deeply scared and uncomfortable, through much of the time that she was believed to be “unconscious,” undergoing painful procedures such as airway suctioning without doctors having taken the time to explain their purpose to her due to her perceived unresponsiveness.12

Furthermore, behaviors that provide evidence of sentience in creatures that are assumed to be capable of it can provide poor or misleading evidence in certain contexts. Consider the rat-grimace scale. Developed in 2011 by neuroscientist Jeff Mogil, the scale is a tool for assessing whether rats are in pain by their facial expressions, employing four “action units” (squinting, cheek flattening, ear-changes, and whisker movement). The assumption that underlies the scale is that rats exhibit reflex facial movements in reaction to nociception, or the detection of harmful influences. And nociception is, under ordinary circumstances, good evidence for pain in animals capable of pain.

However, because these facial responses are reflexes, they are not themselves good evidence that rats have the capacity for pain in the first place. In other words, the rat’s nervous system would produce them even if pain were absent. In fact, it is now widely agreed that any behavior that counts as evidence of sentience in creatures capable of such experience could also be exhibited by creatures incapable of, or not currently undergoing, sentient experience.

For example, a sleepwalker can navigate their house, unlock doors, and make a snack without any awareness, just as a conscious person might do the same while fully awake This ability has impacted a number of criminal trials, such as that of a Canadian man, Kenneth Parks, who was acquitted of murdering his in-laws on the ground that he carried out the actions while sleeping.

One way to reduce our uncertainty about behavioral evidence for sentience is to appeal to evolutionary proximity. Because humans are sentient, there is reason to think that this is also true for creatures closely related to humans, including other mammals, such as rats. In this view, the rat grimace scale is probably reliable (rats are, after all, used in the laboratory because of how their biology models that of humans). However, this does not help with cases where the potentially sentient creature is not closely related to us, as with insects or octopuses, or cases where the behavioral evidence is absent or ambiguous, such as with sleepwalkers or neural organoids.

In these cases, we need some other way of differentiating between behaviors that seem sentient and those that really are — perhaps, by looking under the surface.

The Contribution of Neurophysiology

The reason we can be more confident about sentience in creatures more closely related to us is not prejudice in favor of our more winsome mammalian cousins but because of morphological similarity (“homology”). In other words, a rat’s grimace is better evidence of pain than that of an AI avatar because it was produced by a brain similar to our own. Humans and rats share brain regions known as the anterior cingulate cortex and the nucleus accumbens, which are known to play a role in human pain. These regions have been shown to exhibit similar activity in response to the same cause (for example, a hot surface applied to the back of the hand or paw).

As our understanding of neurophysiology grows, we are increasingly able to base our judgments about sentience directly on the physical systems involved rather than proxies like language or behavior.

A great deal of this increased understanding owes itself to advancements in technology, such as fMRI. A landmark 2006 investigation led by the neuroscientist Adrian Owen sought signs of awareness in the brain of a 23-year-old woman who had entered a vegetative state after sustaining severe brain damage in a traffic accident. The investigators asked her to perform two mental imagery tasks known to activate spatially distinct brain regions in healthy individuals: imagining playing tennis and imagining walking around her house. Amazingly, fMRI scans revealed brain activities nearly identical to those observed in healthy subjects. Owen and his colleagues concluded that the woman was conscious and capable of voluntary mental activity.

Subsequent studies reproduced this result, leading to the establishment of “cognitive motor dissociation” (CMD) as a clinical category for patients who are conscious but incapable of voluntary physical movement. One 2010 study even identified a patient capable of correctly answering autobiographical yes-or-no questions by performing the same mental imagery tasks, raising the prospects of clinical applications not just in diagnosis but also in restoring communication.

As impressive as functional imaging approaches to borderline sentience are, however, they are relatively coarse-grained.13 The spatial resolution of fMRI is limited to millimeters cubed, hundreds of thousands of neurons, and reflects slow changes in blood oxygenation rather than neural firing itself. EEG, a noninvasive test that records the brain’s electrical activity via electrodes placed on the scalp, has better temporal resolution but even lower spatial resolution. These methods are valuable for observing large-scale patterns of neural firings, but they leave out vast quantities of detail in the brains of large animals like humans.

When it comes to smaller animals, the situation is even worse. A fruit fly’s brain, for example, is made up of about 140,000 neurons in a 0.1mm cubed space, meaning that even a state-of-the-art fMRI has a resolution larger than a fly’s brain. If a fruit fly flew into an fMRI scanner and kept still long enough, all we would see is a faint, undifferentiated signal — far too coarse to distinguish even the broad outlines of its brain, let alone the activity of individual neurons.

Fortunately, more precise methods of interrogating the brain structures suspected to be involved in consciousness are becoming available.

For mammals, there are two theories about which region of the brain (cortical or subcortical) is thought to give rise to consciousness. The first theory says that human sentience derives entirely from processes involving the neocortex, the furrowed outer layer of the brain that expanded rapidly in primate evolution and is especially large in humans. This casts doubt on insect sentience, since it suggests that sentience is unique to creatures with a neocortex (only mammals), or something like it (the bird pallium, perhaps).

An alternative theory that has gained ground recently attributes some sentient processes to subcortical activity in the midbrain. An important source of evidence for this theory is that children born with little or no neocortex (a rare condition known as “hydranencephaly”) retain some abilities which, in healthy humans, involve consciousness.

Another data point comes from experimentally “decorticated” mammals. Decortication is a nasty process in which the cortex of a living mammal, usually a cat or a rodent, is surgically removed or destroyed. Few ethics boards would approve such experiments today. But past results suggest that decorticated animals also retain abilities, such as visual orientation, self-defence, and social play, that are ordinarily associated with consciousness. The neuroscientist Bjorn Merker draws on this evidence to argue that core conscious experiences depend mainly on a midbrain system that generates a subjective representation of the animal in its environment without relying on the cortex.

Until recently, neither of these theories had much bearing on the question of insect sentience. There was simply no evidence that insects had anything like the cortical or midbrain structures upon which the competing theories of consciousness focus. Instead, researchers supposed that insect behavior was governed by chains of local reflex circuits, strung along the body, with only minimal coordination from the brain. If so, we would have little reason to think of insect behavior as any more conscious than human reflexes.

However, a 2016 study by neuroethologist Andrew Barron and philosopher Colin Klein suggests this is wrong, arguing persuasively that the insect brain is actually strikingly analogous to the mammal midbrain.

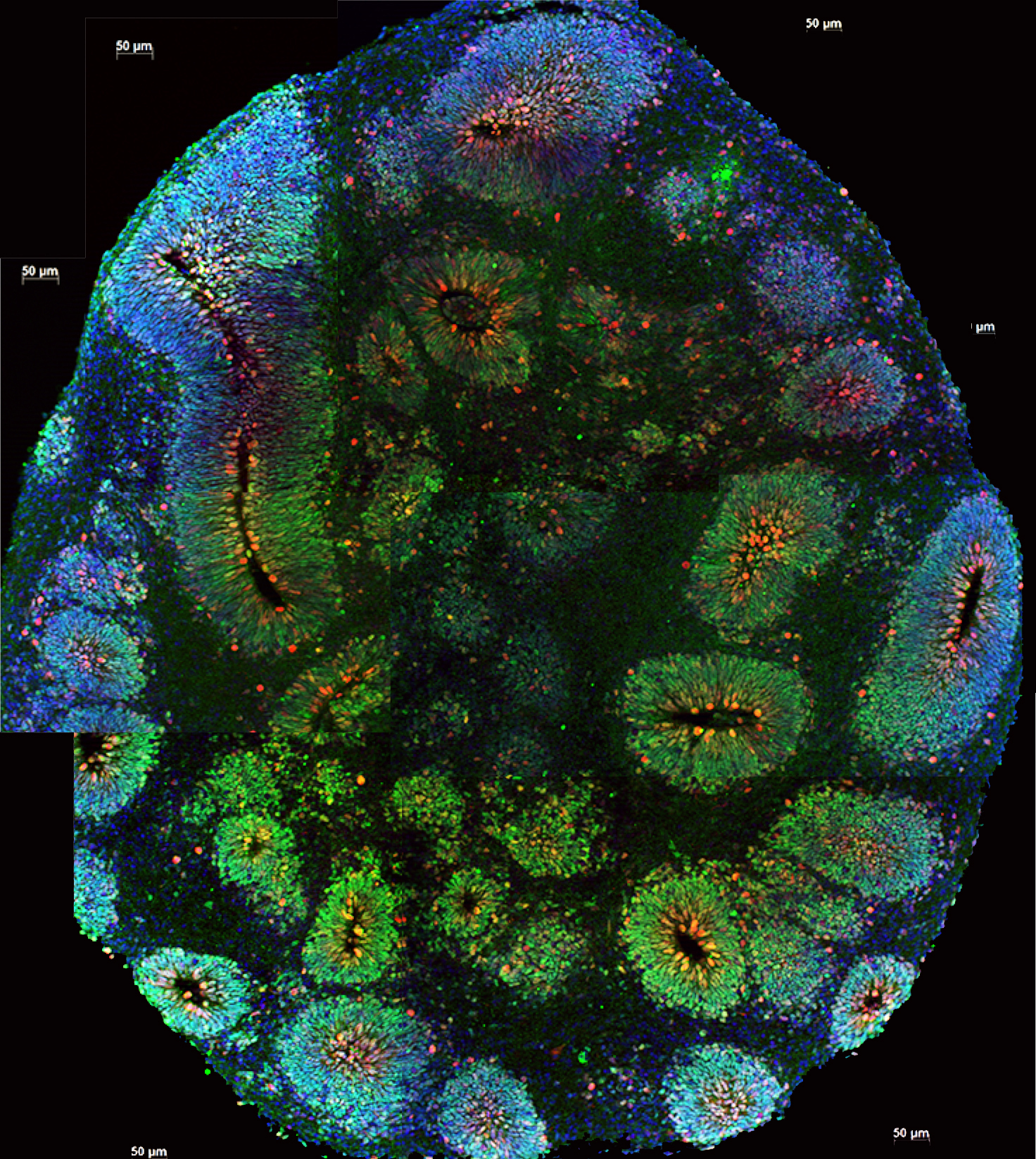

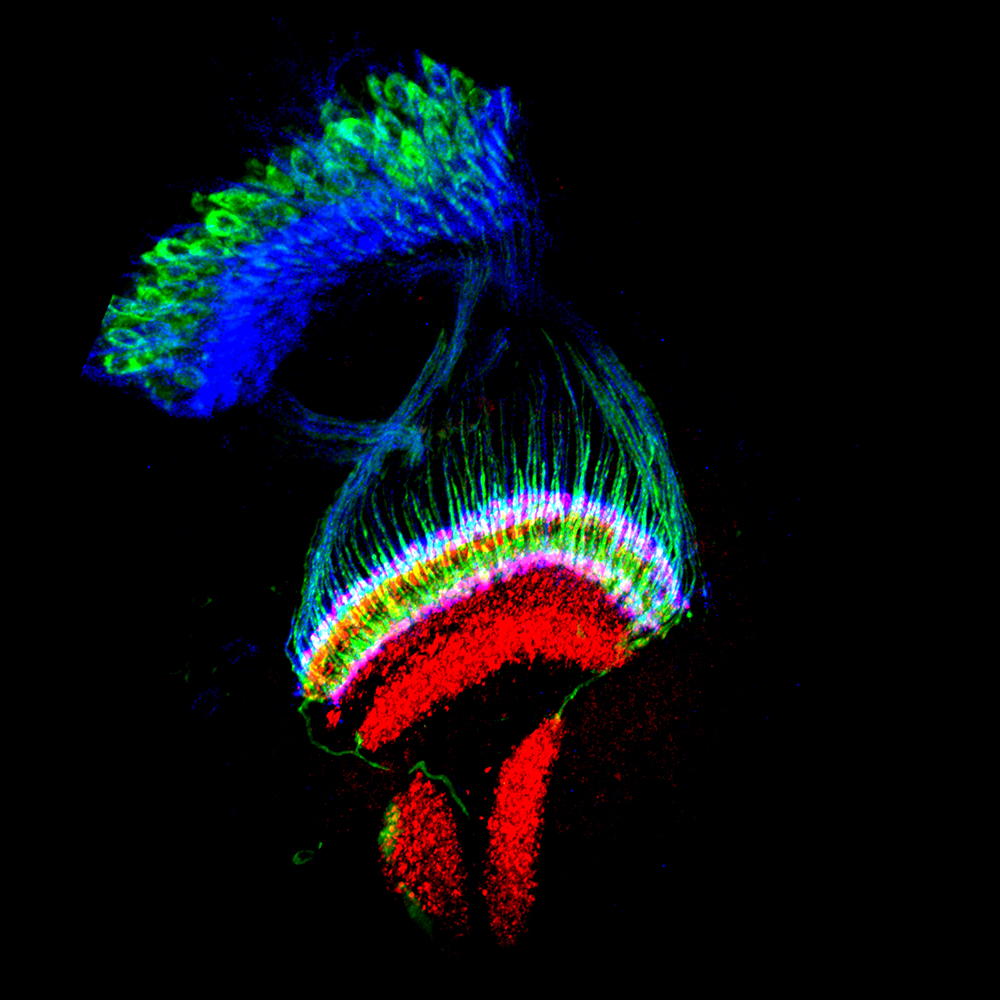

Barron and Klein draw on an impressive range of evidence to make their case. In a particularly compelling study from 2015, a fruit fly is attached to an arm to keep it in place atop a polystyrene ball, suspended by a stream of air. When the fly walks, the ball acts like a treadmill that can rotate in any direction. Its movements control a virtual environment that the fly can navigate. As it does so, its brain activity is monitored by means of two-photon calcium imaging.

Two-photon calcium imaging works by using laser light to excite fluorescent proteins inside neurons, making them glow more brightly as calcium levels rise, a proxy for neural firing. This allows researchers to observe the activity of thousands of individual neurons in real time, far surpassing the spatial and temporal resolution of fMRI.14

What the study found was that a part of the fly’s brain known as the central complex integrates information about the animal’s movements and orientation in space, generating an internal compass-like representation which it uses to navigate. Flies do not merely move by chaining together reflexes triggered by their immediate surroundings but maintain a continuous representation of their orientation and trajectory within their environment, updating it as they navigate.

Given this and other evidence, Barron and Klein argue that the insect brain as a whole is, in fact, functionally analogous to the vertebrate midbrain.15 The central complex in insects serves the role of the vertebrate superior colliculus, processing spatial information for navigation; the insect mushroom bodies perform the functions of the vertebrate basal ganglia, facilitating memory-based action selection, and so on.

From this, we can imagine that if that subsystem is sufficient to determine consciousness in us, then the insect brain is probably sufficient to say it, too, possesses consciousness. If the midbrain theory is correct, then we have good reason to think that not only all vertebrates but also insects are sentient as well.16 This result challenges the consensus against insect sentience and raises uncomfortable questions about their treatment in insect farming and the wild.

The Worm as Standard-Bearer

Barron and Klein’s work, and the experimental research they draw on, would have astonished Darwin. However, they are still focusing on comparatively high-level functional analogies between insect and mammalian brains in their quest to investigate indicators of sentience.

To fully understand the physiological evidence concerning borderline sentience, we need to properly exploit the neural-level data to which we increasingly have access. This brings us to the fast-growing field known as connectomics, which aims to understand the brain at the scale of individual neurons and their connections.17

Tracing the precise interconnections of neurons is a formidable task. After all, neurons are densely packed, morphologically complex, and connected by vast numbers of gossamer-thin electric cables called “neurites.”18 Understandably, connectomics’ pioneers chose to start simple — they, like Darwin, turned to the worm.

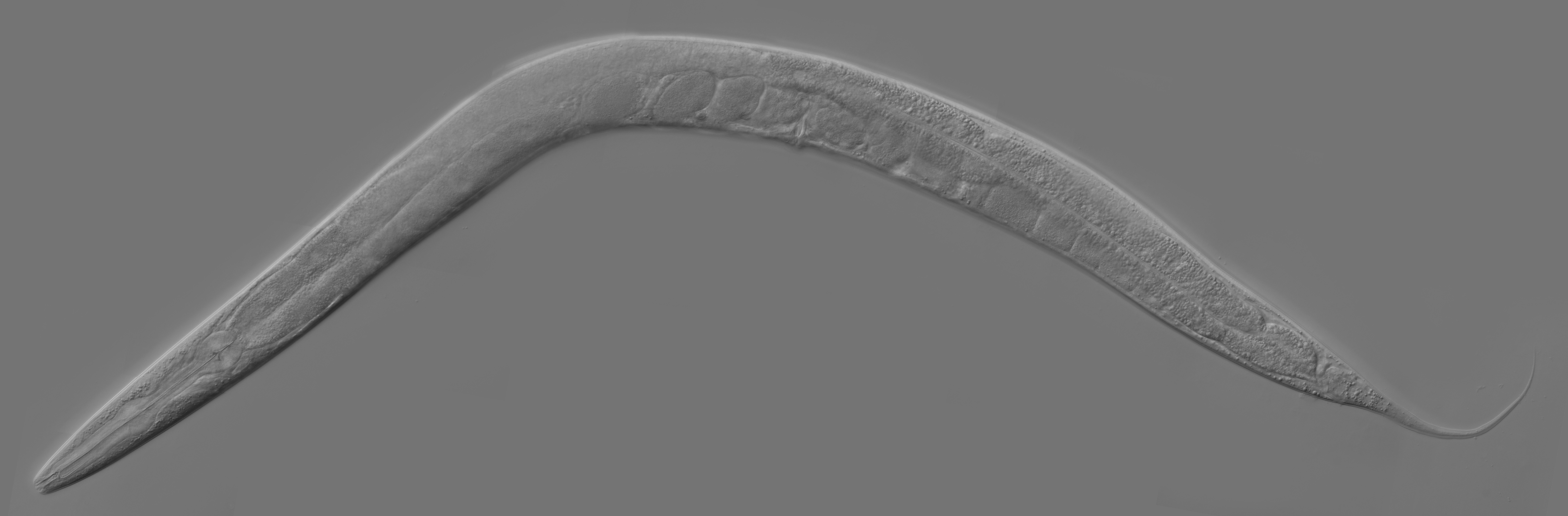

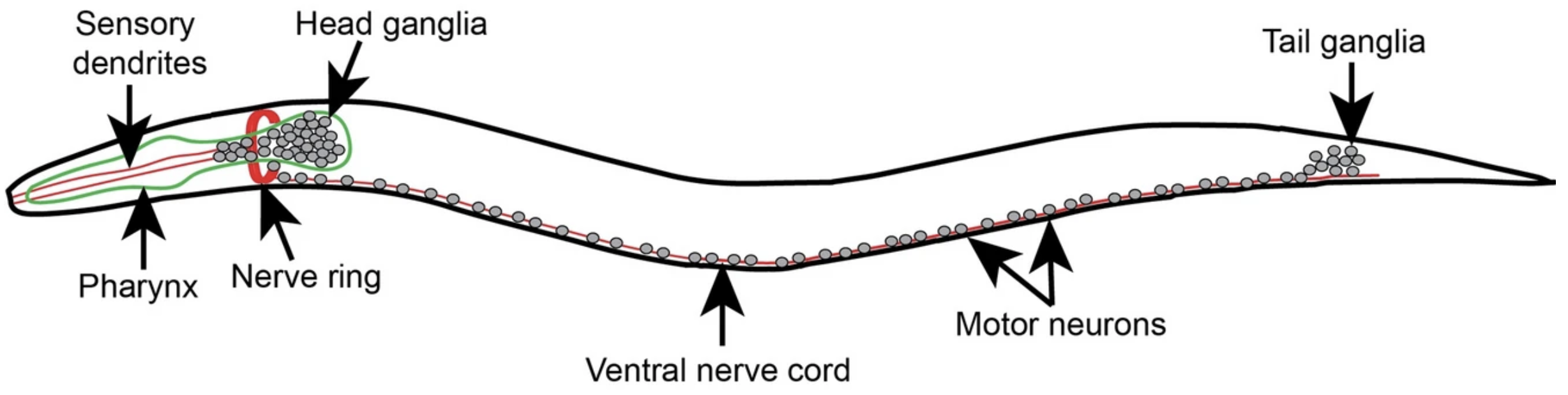

However, they did not use the earthworms that so interested Darwin, but Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans), a microscopic nematode. Nematodes are believed to have changed relatively little since they first emerged 500-600 million years ago. That is (probably) around when centralized nervous systems first developed, and nematodes are among the earliest creatures to possess them. By studying nematodes, we can gain insight into the primordial origins of the brain. Perhaps more helpful, however, is that C. elegans’ nervous system contains just 302 neurons (compared to our 86 billion), making it a perfect model organism for connectomics.

A major milestone came in 1986, when Sydney Brenner’s research team at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge published a detailed wiring diagram of the C. elegans nervous system. The result of an extraordinary effort, it required fixing the worm in osmium tetroxide (a highly toxic oxidizing chemical), sectioning it into several thousand ultrathin slices, and scanning these slices under an electron microscope. The researchers then manually traced neurons and synapses across thousands of images to create the complete map. Where sections were damaged, incomplete, or ambiguous, data from other worms were gathered to fill the gaps.

For decades, the value of this C. elegans connectome was primarily indirect, catalyzing advances in electron microscopes, image analysis, and reconstruction techniques that could help with more ambitious connectomics efforts. Only very recently has it become the subject of physiological research explicitly aimed at investigating sentience.

So far, attention has focused on one topic in particular: the challenge C. elegans poses to the important behavioral indicator of sentience known as motivational trade-offs. These involve the weighing of different drives to optimize behavior.

For many years, researchers have treated motivational trade-offs as especially strong evidence of sentience. After all, they occur when a creature balances different dispositional drives, such as the drive for nourishment or the drive to avoid harm, to optimize behavior. Earlier, we saw an example in Darwin’s observation that earthworms’ desire for sex appears to outweigh their dislike of light.

The French-born Canadian psychologist Michel Cabanac has been researching the role of pain and pleasure in guiding the behavior of animals since the 1960s. After several decades’ work, he advanced what would become an influential theory according to which sentience developed specifically to facilitate such trade-offs. Behaving organisms, Cabanac proposed, require a “common currency” to weigh and rank different motivational drives. Valenced experience provides that currency.

Cabanac showed that apart from its common-sense appeal, his conjecture makes accurate predictions about humans and other sentient creatures under experimental conditions. For example, human subjects tolerate cold or muscular pain for longer when offered a greater monetary reward, choosing to end the task only at the point when the discomfort outweighs the anticipated pleasure of payment. He subsequently expanded this theory, proposing that sentience first emerged in amniotes, the common ancestors of birds, mammals, and reptiles, around the close of the Paleozoic Era (c. 200-300 million years ago), and arose to make motivational trade-offs possible.

As it turns out, motivational trade-offs are more widespread in the animal kingdom than even Cabanac’s expansive theory suggests. Hermit crabs, for example, appear to evaluate many different motivational trade-offs in choosing a new shell, such as size, camouflage potential, and the pugilistic prowess of the current occupant. And in 2022, a study led by Lars Chittka at Queen Mary University, London, showed bumble bees make comparably sophisticated trade-offs weighing the benefits of high-quality food against exposure to harmful heat, resulting in a spate of articles in venues such as IFL Science, Scientific American, and Vox announcing that bees feel pain.

The new examples already strain Cabanac’s theory. If creatures as seemingly simple as crabs and bees can manage trade-offs, perhaps this marker is not as distinctive of sentience as we had hoped. The revelation that C. elegans does the same, and a detailed understanding of how it achieves this, may prove the final straw to upend it.

For their tiny size, nematode worms are surprisingly sophisticated. If you place a damaging fructose or cupric ion barrier between a worm and an odorant that signals food, it will weigh up factors including the strength of the harmful substance, the strength of the odorant, and when it was last fed to determine whether to brave the barrier. Worms are bolder where the barrier is less concentrated or the odorant more so, and well-fed worms are choosier about which food sources they pursue. Likewise, worms are less fastidious about the repellent octanol when food is available. In other words, nematodes make what look like smart — conscious — motivational trade-offs.

At face value, this intelligible weighing of interests might be treated as reason to think that nematodes have valenced experience, pushing the origins of pain and pleasure back 200 million years earlier than Cabanac’s amniote theory. Some researchers are willing to entertain nematode sentience. But others draw the opposite conclusion. For example, a 2020 paper by the philosopher Elizabeth Irvine proposes that the C. elegans nervous system, with its 302 neurons, is too simple for consciousness, and that there must therefore be something wrong with the idea that such behaviors provide good evidence of the capacity for sentience.

Irvine draws this conclusion from the overall simplicity of the C. elegans connectome, principally the small number of neurons and connections that make it up, rather than the specific organization of those cells for complex behaviors. A more recent paper by Oressia Zalucki and colleagues at the University of Queensland’s School of Biomedical Sciences attempts something more challenging. Alongside the philosopher Deborah Brown and neuroscientist Brian Key, Zalucki sets out to identify the specific neuronal circuitry underlying motivational trade-offs in C. elegans. Her stated aim is to identify the “minimal neuronal circuitry needed to generate subjective experience” (in effect, determine whether nematodes are sentient).

Finding the precise neuronal circuitry driving a behavior means taking connectomics beyond static structure to dynamic functions. The basic methodology consists of identifying neurons that are necessary for a behavior (whose loss impairs it) and those that are sufficient for the behavior (whose stimulation triggers it). Since the 2010s, this has usually been achieved by optogenetics, which allows individual neurons to be activated or silenced in response to light by genetically engineering them to express light-sensitive ion channels. Other methods include laser ablation and electrical stimulation. Researchers can thereby seek to identify the entire circuit underlying a behavior. The C. elegans touch-withdrawal and egg-laying circuits are two classic examples identified in earlier research.

Zalucki and her colleagues attempt to do the same thing for the trade-off a worm makes when it detects the noxious chemical octanol in the direction of a potential food source. In food-rich conditions, the worm briefly turns tail before returning to seek more food; when hungry, it hesitates longer before retreating but sticks with the decision longer once made. Drawing on a wide range of prior studies, Zalucki identifies a circuit of two sensory neurons and three interneurons (those that fall between sensory and motor neurons) that facilitate this trade-off. The two sensory neurons detect the competing influences of food and octanol, two interneurons modulate the worm’s response, and a third interneuron signals the command to motor neurons.

The circuit identified by Zalucki has two features that are relevant to the relationship between motivational trade-offs and sentience. First, even for the 302-neuron nematode, this 5-neuron circuit is extremely simple. Secondly, there is nothing in the functional organization of the circuit to distinguish it from the kind of unconscious reflex circuits that have been reconstructed, albeit less exhaustively, in studies of mammals. For example, similar structures have been observed to mediate the stretch reflex in mammalian spinal cords, as well as unconscious processes in the retina and primary visual cortex.

Zalucki’s findings are physiologically unremarkable; after all, few would be surprised to find that C. elegans’ behavior is achieved by a simple circuit of the kind they identified. But the implications for the connection between motivational trade-offs, a classic behavioral marker of sentience, are significant.

First, if simplicity counts against sentience, as most researchers agree it does, then the great simplicity of the circuit underlying this trade-off counts against its being sentient. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, if similar circuits in mammals are known to mediate unconscious reflexes, then it seems reasonable to suppose that the nematode circuit operates unconsciously, too.

Like Irvine, Zalucki argues against the notion that motivational trade-offs are evidence of sentience. But others are more agnostic. A recent paper by Simon Alexander Burns Brown and Johnathan Birch proposes that rather than abandon the idea of motivational trade-offs as evidence of sentience, we should refine it, adding other criteria such as the “prospective weighing of risk and opportunity, integration of information from many different sources.” Either way, it is clear that motivational trade-offs are not by themselves the first-rate evidence of the capacity for sentience they have sometimes been taken to be.

While challenging the notion of motivational tradeoffs as evidence of sentience is impressive in its own right, this is not even the most remarkable thing about Zalucki’s finding. It is that she did it by investigating the question, for the first time, at the level of individual neurons.

The Future

Something notable about both Zalucki’s and Barron and Klein’s work is that they draw conclusions about borderline cases by contrasting them to the paradigmatic case of healthy adult humans. This is likely to remain central to the field’s methodology. For this reason, our ultimate goal should be to seek out the same kind of neuron-scale structural and functional understanding of the human brain that we have of nematodes.

This is a tall order. While connectomics research is advancing, it’s an extremely nascent field. In terms of truly complete, neuron-to-neuron wiring diagrams of an entire nervous system, we’re still limited to a handful of relatively small invertebrates (C. elegans, Drosophila, and a couple of marine larvae). The jump from fruit fly (~140,000 neurons) to something like a mouse brain (~70 million neurons) or human brain (~86 billion neurons) remains an enormous technical challenge.

This challenge is compounded by the fact that mammalian brains are not just larger and more complicated than those of nematodes and fruit flies; they are also much more variable. The nematode and fly brains are highly stereotyped, meaning that evidence from one sample has great value for understanding the whole species. This is not possible to the same degree for other animals. An accurate map of your brain would differ in important ways from that of another human. In fact, due to plasticity and cell turnover, it would even differ from your own a few years before or after such a study was done.

Even if we were able to draw a full map of neural connections for individual human brains, it isn’t clear that the neuronal level is fine-grained enough to give us a complete picture of sentience. The idea that the neuron is the “functional unit” of the brain suggests that we can understand the distinctive activities of the brain while setting aside finer detail. Increasingly, however, researchers see smaller components as making a non-negligible contribution, from glial cells to molecular concentrations and even, on some radical views, quantum effects in microtubules. The more that research suggests that smaller-scale entities influence brain processes, the more difficult it will be to gather all the physiological evidence that bears on questions of sentience.

The perception that the nematode nervous system is a simple mechanism because it has only 302 neurons itself holds only to the degree that complex subcellular processes do not significantly modulate its functioning. This assumption might be deeply mistaken. There exists a longstanding project to emulate the nematode nervous system in a computer that can operate a robotic worm body. This project, known as OpenWorm, has proven remarkably difficult to solve. After 15 years’ effort, it still remains a work in progress, reflecting how little we really understand even this paradigmatically simple nervous system.

Setting aside the uncertainties that surround the nascent field of connectomics, there remains significant disagreement over more established neuroanatomy and physiology. For example, the midbrain theory of sentience, on which the whole of Barron and Klein’s theory of insect sentience depends, is itself controversial. Brian Key, the senior contributor to Zalucki’s paper, is one of the most forceful opponents of the midbrain theory, arguing that human sentience depends on distinctively mammalian cortical structures, and that even many vertebrates, fish in particular, are therefore unconscious. There exist formidable methodological difficulties in adjudicating this disagreement.19 The problem only grows when we move beyond organisms to the possibility of machine consciousness, where we lose even the modest guidance offered by common biology.

This is troubling, as so much rides on getting our theory of the neural correlates of sentience right. We look back with horror now at the practice of conducting surgery on infants without anaesthesia. Until the early 2000s, patients diagnosed as “permanently vegetative” were commonly denied attempts at rehabilitation, medical care, or even food and water, on the assumption that there was “no one there.” If, as we now think, even a small fraction of these patients were aware, these protocols may have been unknowingly barbaric.

Yet, excessive credulousness about sentience also carries real costs. For example, animal ethicist and activist Gary Francione points out that defenders of plant sentience risk undermining the rationale behind protections for animals. After all, the idea that even plants have feelings suggests that we need not provide greater protection to cats and cows than we do to the grass beneath our feet. Likewise, when Blake Lemoine lost his job at Google for claiming their chatbot had feelings, it was both bad for him and awkward for his employer. Furthermore, if he had been successful in convincing others, the consequences could have done incredible damage to the entire AI industry. Genuine reasons to think AIs are conscious might make this an acceptable sacrifice, but a misguided belief that chatbots feel could be economically disastrous.

In the same way, if there is a serious chance that insects are sentient — and it seems there is — then we have a moral obligation to rethink how we treat them. But falsely assuming that insects require sentience-based consideration could impose a massive and unnecessary cost on scientific research and the large and growing insect food industry.

There is no shortcut for addressing these challenges, only a desperate need for more research. This will require additional connectome maps and experimental evidence linking them to the kinds of processes, such as motivational trade-offs, that have been taken as proof of sentience. A good first step would be to identify the neural circuitry underlying trade-offs in nematodes other than the food-octanol example that Zalucki investigates. We might move from there to more complex organisms and to other sentience markers, always combining fine-grained connectomics data with more coarse-grained physiological and behavioral evidence.

There is a vast distance to cover before we reach anything like the ideal goal of understanding large mammalian brains at a neuronal scale, but even partial progress could yield substantial payoffs. A better scientific understanding of borderline sentience could help unlock technologies that influence or are controlled by mental states. Promising applications include neuro-prosthetics that restore functions lost through illness or injury, as well as new alleviants such as painkillers and anti-depressants. Technology companies are already exploiting these advances to develop impressive new products such as Neuralink’s brain-computer interfaces or Vertex Pharmaceuticals’ breakthrough non-opioid painkiller. Likewise, researchers in this field are already having a real-world policy impact. Johnathan Birch was able to convince the UK government to recognize cephalopod sentience using a range of existing behavioral and physiological evidence.

Ultimately, investigation into borderline sentience remains both technically and scientifically challenging. Yet for those of us who share Darwin’s curiosity about the frontiers of mind and experience in worms, bats, and other creatures, the path forward is not just practically important but also intellectually fascinating.

{{signup}}

{{divider}}

Ralph Stefan Weir is a philosopher at the University of Lincoln. He also writes for Works in Progress and Psychology Today.

Acknowledgments: Thanks to Jun Axup for providing feedback on an earlier version of this draft, to Lauren Kane and Sebastian Seung for valuable conversations, and to Xander Balwit for contributing to the development of this piece. Lead image by Mariya Khan.

Cite: Weir, R.S. “What It’s Like To Be A Worm.” Asimov Press (2026). DOI: 10.62211/27hw-58nw

Footnotes

- Darwin (1837, 36), cf. Colin Allen and Michael Trestman (2024, § 3).

- Number estimated from limited available data.

- The most influential activist was Jill Lawson, whose son Jeffry underwent open heart surgery without anesthesia.

- Although Nagel’s skepticism about the ability of physical science to describe consciousness remains controversial, his definition has become a standard starting point for researchers.

- These examples highlight that sentience is broader than just the capacity for pain and pleasure. Breathlessness and nausea are not exactly what we would call “painful,” but they certainly have negative valence.

- Today, researchers have devised further diagnostic categories distinguishing persistent vegetative state from the “minimally conscious state minus” and “minimally conscious state plus,” in which patients exhibit certain signs of voluntary action, as well as “cognitive motor dissociation,” in which patients are conscious but unable to produce physical responses.

- For many, this may bring up questions about abortion. However, philosopher Jonathan Birch observes that debates about abortion usually focus not on fetal sentience but personhood (that is, who is considered a “person” in the eyes of the law and society). Birch does, however, criticize the hesitancy of medical bodies to acknowledge the possibility of early fetal sentience in the context of abortion.

- The other main candidate for non-human, non-animal sentience is plants. Only a small minority of researchers recognize evidence for plant sentience, though there do exist philosophical arguments for thinking sentience more widespread than we suppose.

- The authors conclude that although no existing system meets enough indicators to make it a good candidate for consciousness, most or all such indicators can, in principle, be met.

- For now, at least. Ethan Perez and Robert Long have proposed a strategy for using self-report as evidence for AI sentience in the future, and Susan Schneider proposes a restricted approach to training algorithms aimed at similar results.

- See, for example, Sneddon et al. (2014). As Irvine (2020) comments, while Sneddon’s proposed markers are not all purely behavioral, most are assessed via observed changes in behavior. For an early example, see the UK 1965 report on the welfare of intensively farmed animals, which would serve as a model for later reports. While an early section emphasizes the anatomical and physiological similarities of bird and mammal nervous systems with those of humans, it goes on to rely almost entirely on behavioral markers.

- A distressing process in which a catheter is connected to a suction machine that removes mucus and saliva from the airway so the patient can breathe.

- Not to mention expensive and cumbersome: fMRI requires that the patient lie in a large, noisy, immobile, and expensive scanner. MRI scanners for functional imaging, the kind that measures activity, not just structure, typically cost over a million dollars.

- Two-photon calcium imaging is not a direct replacement for fMRI, however. Its reliance on light transmission means that the brain must be visible for measurement and the light can’t penetrate deeply into larger brains. But, it is ideal for interrogating the neurobiology of the fruit fly.

- Barron and Klein published two color-coded figures of the mammalian (Fig. 1B) and insect brain (Fig. 2) that clearly illustrate the comparative anatomy and functions.

- The evidence for the midbrain theory, if accepted, does not have to be interpreted along the lines of Merker’s theory. Theories of consciousness are so varied that just about any characteristic of the midbrain might be regarded as a candidate for the basis of conscious experience. Still, Merker’s theory is influential with good reason.

- I use “connectomics” for the general attempt to understand the brain at the scale of individual neurons and their connections, whether focusing on the whole brain or a smaller region, static structure, or functional organization. This increasingly common usage contrasts with a narrower use of “connectomics” exclusively for the project of building static whole-brain maps.

- Neurites are the projections from the neuron cell body that send and receive electrical signals with other neurons, via axons and dendrites, respectively. The juncture at which two neurons exchange a signal is known as a synapse. The human brain has been estimated to have 1013-1015 synaptic connections, that a cubic millimeter of the cerebral cortex has a billion synapses.

- Birch explains how the evidence tends to underdetermine theory choice in this area.

Always free. No ads. Richly storied.

Always free. No ads. Richly storied.

Always free. No ads. Richly storied.