A Brief History of Xenopus

Until the 20th century, there was no easy way to detect a pregnancy. One could wait for two missed menstrual cycles, watch for the first signs of a baby bump, or listen closely for a fetal heartbeat, but none of these methods work until several months into gestation. Ancient and medieval sources describe a variety of possible tests to determine whether a person was pregnant, but none were remotely reliable by modern standards.1

In the 19th and 20th centuries, researchers began looking for a solution in the emerging science of endocrinology, the systematic study of hormones. It was during this era that doctors and biologists began to shift from studying anatomy (observing the mechanics of visible organs) to exploring the invisible potency of “internal secretions” and “juices” that directed bodily phenomena. Early experiments by endocrinologists were crude, however, usually involving the injection of fluids from one animal (or human) into another and seeing what happened.

One pioneering endocrinologist who predicted the existence of hormone chemicals was Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard. In 1889, he shared results from a “study” in which he injected himself with an elixir of “the three following parts: first, blood of the testicular veins; secondly, semen; and thirdly, juice extracted from a testicle, crushed immediately after it has been taken from dog or a guinea-pig.” Brown-Séquard found that these testes-semen injections restored to him all the vigor of his youth, though few others have been able to reproduce his results.2

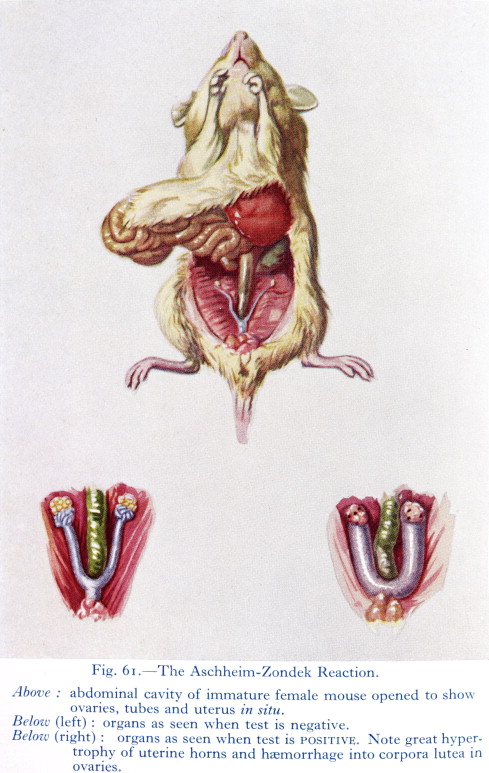

In this spirit, two doctors working in Berlin, Selmar Aschheim and Bernhard Zondek,3 discovered an early pregnancy test in 1928 by injecting patients’ urine into laboratory mice. A few days after the injections, the mouse would be killed and dissected so that its ovaries could be examined; if the patient who provided the urine sample was pregnant, the mouse would develop “ovarian blood spots.”

In the U.S., Maurice Friedman adapted this approach for rabbits because a single rabbit could handle a larger volume of urine, their ovulation patterns are a bit more reliable, and clinical centers generally found them easier to house. His “rabbit test,” released in 1931, became the American standard for several years. Yet both the mouse and rabbit tests had significant drawbacks: they required waiting several days for results, and the animals had to be euthanized or at least operated upon to check for signs of ovulation.

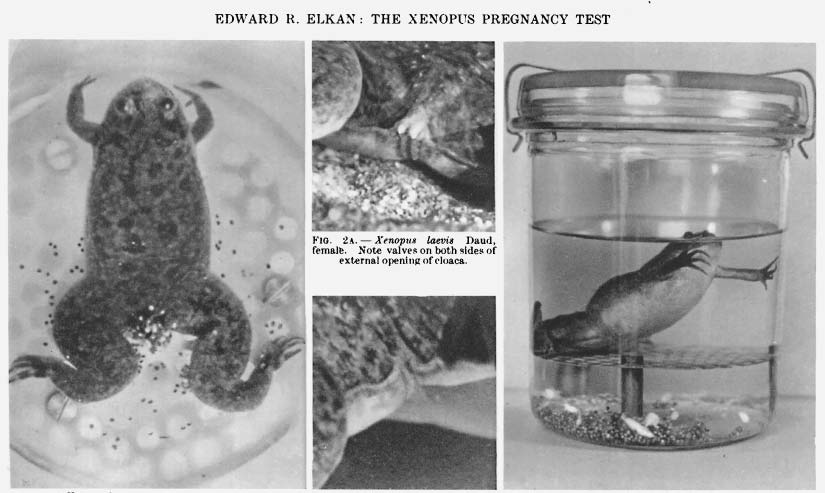

It was around this same time that a British scientist living in South Africa, Lancelot Thomas Hogben, injected some ox pituitary extract into an African clawed frog, Xenopus laevis, as part of his efforts to understand how hormones influence ovulation. It did not take long for Hogben to realize he had struck gold (or rather, eggs) because, just hours after the injection, the frog laid many hundreds of them. Thrilled by this discovery, two former students of Hogben’s, Hillel Shapiro and Harry Zwarenstein, demonstrated that these African frogs would be much more suitable for pregnancy tests than mice or rabbits.4

Reliably, these frogs would ovulate within 18 hours of being injected with the urine sample of a pregnant person, laying easily visible eggs at any time of year. Unlike the rabbit test, this new “bioassay” was faster and left the animal perfectly unharmed for future use. Word spread quickly, and within a few years, biological institutions everywhere were inundated with ovulating Xenopus frogs.

Thanks to the discovery of the specific “pregnancy hormone” (chorionic gonadotropin, or hCG) and lateral flow devices that can detect its presence, modern-day pregnancy tests do not require rabbits, frogs, or indeed, any other animal. But their widespread use for pregnancy testing was what likely helped entrench Xenopus laevis (and a few of its cousins) in scientific research.

Xenopus frogs possess a strangely zen-like charisma. Their lidless eyes protrude from the tops of their flat heads, and when not feeding, swimming, or mating, they tend to laze in the water and stare at you. They lack tongues; instead, they open their maws and shovel in prey with their front feet as it passes. These same feet allow them to grip females during mating, while they use their webbed back feet, equipped with distinctive black claws on the last three toes, to swim. These appendages inspired their name, “Xenopus,” which means strange-footed.

The sudden abundance of Xenopus in laboratories during the 1930s and 40s may seem like a stroke of luck for biologists, but in truth, frogs were not newcomers to biological research. Well before Xenopus frogs were used as “obstetrical consultants” (as one scientist referred to such animals), many other frog species played a role in developmental biology research.

The main reason for this was convenience: frogs are relatively easy to find, catch, and house, as anyone who grew up near a pond can attest. They also lay many eggs at a time, and their eggs are generally larger than most fish eggs but unencased by hard shells like bird eggs, making them excellent research subjects for understanding embryonic development.

The most prominent early frog experiments were performed way back in the 18th century by Italian scientist, Lazzaro Spallanzani (whose other accolades include the discovery that bats use echolocation and that digestion harnesses the chemistry of gastric juices). By brushing unfertilized eggs with frog sperm, Spallanzani proved that fertilization could occur outside the female body — a finding he later confirmed in mammals through the successful in vitro fertilization of a dog.

Perhaps his most memorable experiment, however, was his demonstration that it was specifically semen that caused fertilization. He proved this using a negative control: Spallanzani sent off male frogs to “seek the females with equal eagerness, and perform, as well as they can, the act of generation” while wearing miniature taffeta breeches that he had meticulously sewn for their tiny legs, preventing their semen from reaching any eggs. The result of this experiment, he wrote, “is such as may be expected: the eggs are never prolific [e.g., fertilized], for want of having been bedewed with semen, which sometimes may be seen in the breeches in the form of drops.”5

Over the next hundred years, European scientists continued to make crucial discoveries in the burgeoning field of embryology by manipulating amphibian eggs. However, these studies were usually done using locally available species, such as frogs from the genus Rana (which includes most common pond frogs of Europe, Asia, and North America). It was a century and a half after Spallanzani sewed his silk condom-pants that American and European biologists found themselves with an abundance of Xenopus eggs on their hands thanks to their use in fertility testing.

The same qualities that made African clawed frogs attractive for pregnancy testing also made them excellent laboratory models; they do fairly well in captivity. Xenopus are fully aquatic species6 with simple needs, at least by most amphibian standards. They eat almost anything, can survive in tap water,7 and can live for up to twenty years. And a single brood from these frogs yields hundreds to thousands of eggs at a time.

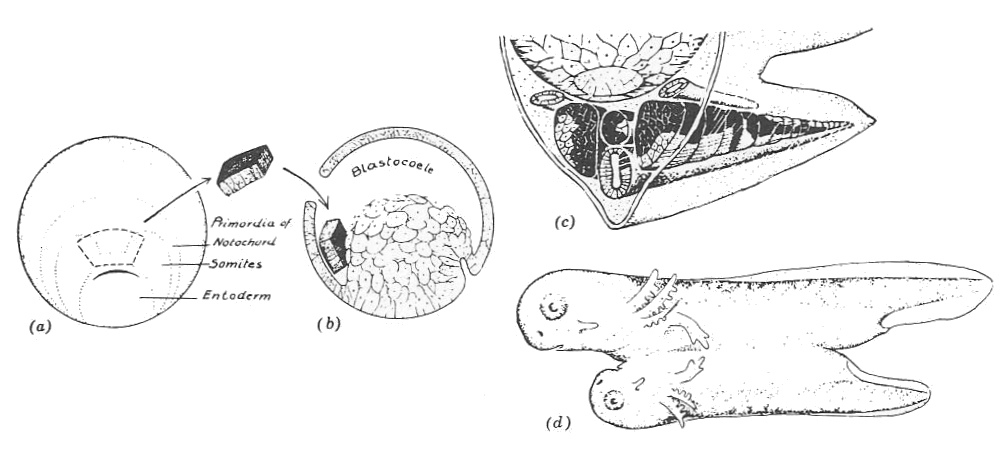

For scientists, these eggs are far more interesting than the adult frogs. Just one-tenth the size of a typical marble, but clearly visible to the naked eye, these two-toned eggs are dark on one side and light on the other, a pattern reminiscent of a Poké Ball. The contrast between these two colored sections (with a grey crescent in between) becomes more pronounced after fertilization, when the pigmentation concentrates at the site of sperm entry. This darker half of the egg is known as the “animal” pole, the half which will divide into smaller cells more quickly, and is thus more “animated” relative to its “vegetal” pole, the lighter-colored half characterized by dense yolk.

Today, one can find numerous videos showing how no special dyes or equipment (beyond, perhaps, a magnifying lens) are necessary to observe the early rounds of cellular division in Xenopus eggs; meticulous work by dozens of scientists has since determined which organs will arise for these early cell divisions.

Beyond their visual properties, frog eggs are also useful research subjects because their embryos are easily manipulated; eggs can be poked, prodded, and even completely torn apart while still maintaining the capability to develop into tadpoles. One of the most beautiful experiments from early embryology, conducted by Hans Spemann and his student Hilde Mangold8 in the 1920s, was originally done in newts, but can be easily replicated in frog eggs: if you remove a small piece of tissue off one amphibian embryo and attach it onto a second, this ripped-off chunk of cells will develop along with the “donor” egg such that the resulting tadpole grows to have two fully formed heads.

Spemann and Mangold’s extraordinary discovery sparked an international race, from Japan to the United States, to identify the chemical factors responsible for the activity of the “organizer” tissue, as Spemann and Mangold called it. The “miners” of the time, however, lacked the metaphorical tools needed to dig up the secrets of these organizer cells. Although they knew, generally, that all biological traits were controlled by chromosomes housed in the cell’s nucleus, they did not know how those chromosomes gave rise to genes.

That changed in 1953, when Watson and Crick published their celebrated papers describing the structure of the DNA molecule and how it suggested a mechanism of gene inheritance. The work over the next decade that would unveil the secrets of the genetic code was mostly done in simple models such as bacteria, viruses, or yeast cells. But it was, incidentally, a Xenopus experiment that provided the most dramatic demonstration that even adult animal cells retained the entire genetic library of information necessary to recreate an organism.

In 1968, following experiments by Robert Briggs and Thomas King showing that the nucleus of one cell can be successfully transferred into another, developmental biologist John Gurdon took the nucleus from an adult frog cell and injected it into an egg whose nucleus had been removed. The resulting egg, now carrying DNA from an adult “parent,” was capable of growing into a normal tadpole and then adult frog, with all the varied cell types of a normal animal. This new frog was a “clone,” from the Greek word for “twig,” being grown, as it were, from a clipping of an adult tree instead of from a seed.9 Dolly, a sheep cloned in 1996, gained notoriety as the first cloned mammal, but the first animal cloned from an adult cell was actually a Xenopus frog, nearly three decades earlier.

Today, if you overhear a molecular biologist talk about their “cloning work,” they are unlikely to be discussing attempts to make an identical twin out of a grown animal. Instead, they are probably speaking about the cloning of specific genes; synthesizing or copying the sequence of a gene (the specific combination of DNA chemical letters that spell it out) and amplifying it by taking advantage of the rapid proliferation (and gene copying capacity) of the bacterium E. coli. However, this still routes us back to the frog, as this basic technique of having bacteria express a gene from a eukaryote was first achieved with the successful cloning of a Xenopus gene in 1974.

Genetic cloning was made possible by three discoveries: restriction enzymes, molecular scissors that cut DNA at specific sequences, ligases that could rejoin those fragments into new arrangements, and the idea of including antibiotic resistance genes alongside the cloned gene so that successful constructs can be identified using antibiotics. Herb Boyer at UC San Francisco, who had purified the restriction enzyme EcoRI (and would go on to found Genentech, widely regarded as the world’s first biotechnology company, in 1976), conceived the idea alongside Stanford bacterial geneticist Stanley Cohen while the two were discussing their research over sandwiches at a Hawaiian deli in 1972.10 After transforming bacteria with their stitched-together plasmids, Boyer recounted checking the results: “I went to look at the gels in the darkroom, and there it was. It actually brought tears to my eyes, it was so exciting.”

Boyer and Cohen, along with other scientists, soon went further than introducing bacteria-derived genes back into other bacteria. In 1974, their team spliced the Xenopus ribosomal RNA gene into E. coli cells. This frog gene was selected because it had been thoroughly “characterized and can be isolated in [a large] quantity.” This extraordinary result demonstrated that bacteria could be coaxed into reading and copying genes from across a billion-year evolutionary divide, laying the foundation for the fields of genetic engineering, synthetic biology, and biomanufacturing.

For all its upsides, however, Xenopus laevis had its shortcomings. The frog, so favored for its use in fertility testing and embryology, turned out to be poorly suited to genetic research because, instead of having two copies of each of its genes (one from each parent), it has approximately four of each. This chromosomal messiness is not uncommon in nature, but having four similar — but not identical! — copies of their chromosomes makes sequencing laevis genomes significantly more difficult. A complete laevis genome assembly wasn’t released until 2016, trailing a decade or more behind other model organisms such as Mus musculus (mouse) and Rattus norvegicus (lab rat) or agricultural workhorses like Bos taurus (cow) and Gallus gallus (chicken).

Even without a solid understanding of Xenopus genetics, however, biologists in the 1980s found another remarkable way to put Xenopus eggs to good use. Eggs are essentially large cells; thus, a scientist with a large supply of eggs is also in possession of many easily manipulated cells. Just as young frog embryos remain intact after being prodded by needles, the cellular components of frog eggs remain biologically active even after those cells have been gently crushed and separated away from their yolks, chromosomes, and heavier components, thanks to the marvels of centrifugation. This cellular extract could be generated in large quantities, and the resulting soup of proteins and organelles would still carry out many of the most intricate operations of a cell, but in a more easily observable and controllable system.

.jpg)

Because these systems are not cells, but contain almost everything inside cells, they have been especially useful for understanding the amazingly well-coordinated mechanisms of cell division. Xenopus egg extracts were essential in the discovery of proteins that control the cell cycle, the dance of chromosomes as they arrange themselves for cell division, the self-assembly of structural proteins called microtubules as they direct and move those chromosomes, and the role of small messenger proteins, called Rans, in many aspects of cellular activity. What made all these discoveries possible is not only the fact that the components of these cell-free extracts are easily visualized, but also that they are exposed; there is no membranous barrier between the cellular components or any chemical that a scientist may wish to introduce into the system (or remove, such as by fishing out proteins using antibodies).

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, scientists looking to conduct genetic research on Xenopus frogs without the genetic challenges of X. laevis did some chromosomal explorations of related species, and by the late 1990s, hit upon Xenopus tropicalis, a species that possesses many of the advantages of X. laevis but has only two sets of each chromosome instead of four. Some labs switched to using these frogs, but many groups that had well-established protocols for X. laevis were reluctant to do so, especially since Xenopus tropicalis requires different housing and handling conditions. Xenopus tropicalis frogs are also smaller than X. laevis, with smaller eggs and brood sizes. Thankfully, genetic engineering has advanced a great deal over the past two decades, and today both X. laevis and X. tropicalis are commonly used in biology research.

Even if much more is known now than in the 1930s, when Xenopus frogs were first hopping around research labs, they are still being used to solve pressing questions of basic biology, as vertebrate animal models for drug development and testing, and in experiments whose findings may only be fully understood in years to come. Thanks to their historic role in the science of fertility and embryology, four African clawed frogs were even lucky enough to be astronauts in 1992, when they boarded the Space Shuttle Endeavour to test whether or not reproduction and development could occur in zero gravity. These frogs were indeed capable of laying eggs and producing viable offspring while aboard the space shuttle. After all, nobody forced them into wearing pants.

{{signup}}

{{divider}}

Matt Lubin is a PhD candidate studying microbiology at Johns Hopkins University.

Acknowledgements: The author thanks Dr. Ross Pederson and Dr. Christine Field, scientists who currently work with Xenopus, for their helpful comments and corrections, as well as the editorial team of Asimov Press.

Cite: Lubin, M. “A Brief History of Xenopus.” Asimov Press (2026). DOI: 10.62211/86wn-33ro

Footnotes

- One of these tests described in a papyrus from Ancient Egypt frequently copied in the ancient world involves checking whether or not the urine of a potentially pregnant person is capable of germinating cereal grains. This may indeed have some validity considering what we now know (and test for) regarding pregnancy hormones, but the variations in these centuries-old texts make them hard to evaluate.

- More on the riveting history of endocrinology can be found in Randi Hutter Epstein, Aroused: The History of Hormones and How They Control Just About Everything (Norton & Company, 2018).

- Both of these Jewish physicians had to flee Germany with the rise of the Nazis a few years later; Aschheim to Paris and Zondenk to Palestine.

- Over a decade later, Hogben would claim that it was his original idea to use Xenopus frogs for pregnancy testing and that papers by Shapiro and Zwarenstein actually delayed their clinical use; the latter two scientists responded with a sharply worded communication of their own, disputing his “recollection” of both their presence in his laboratory as well as the publications pertaining to the Xenopus tests.

- Although Spallanzani drew no pictures of these frog pants, he did describe his feelings towards them: “The idea of the breeches, however whimsical and ridiculous it may appear, did not displease me, and I resolved to put it in practice.” More on this story can be found in Edward Dolnick’s book, The Seeds of Life: From Aristotle to da Vinci, from Shark’s Teeth to Frog’s Pants, the Long and Strange Quest to Discover Where Babies Come From (Basic Books, 2017).

- Although they do breathe air and must occasionally breathe through their nostrils; when a frog is recovering from surgery (1:11:30), it must sit on a platform holding its nostrils in air because it will drown if left underwater while anesthetized.

- Though not just any water. Xenopus are still sensitive to water conditions, especially metal content. Even if they are easy to house by laboratory standards, they may be less so for the home aquarist who will need to carefully monitor water conditions.

- Although Spemann would be awarded the Nobel Prize in 1935 for this work, Hilde Mangold was no longer alive to share the accolades. At the age of just 26, when her paper associated with her doctoral research was about to be published, she died tragically when her kitchen’s gasoline heater exploded.

- Although animal cloning worked, success rates of early attempts were very low; it often took dozens to hundreds of tries before a cloned egg would reach adulthood. Half a century after his own cloning experiments, John Gurdon published seminal papers demonstrating why that is the case: although (nearly) every adult cell contains the entire genome, the genome maintains its cell-specific “memory” thanks to modifications of histones, the proteins that hold the DNA in place, among other mechanisms.

- The historical and ethical context for these experiments is explored in Siddhartha Mukherjee's The Gene: An Intimate History (Scribner, 2016) and Matthew Cobb, As Gods: A Moral History of the Genetic Age (Basic Books, 2022).

Always free. No ads. Richly storied.

Always free. No ads. Richly storied.

Always free. No ads. Richly storied.