Making the Vortex Mixer

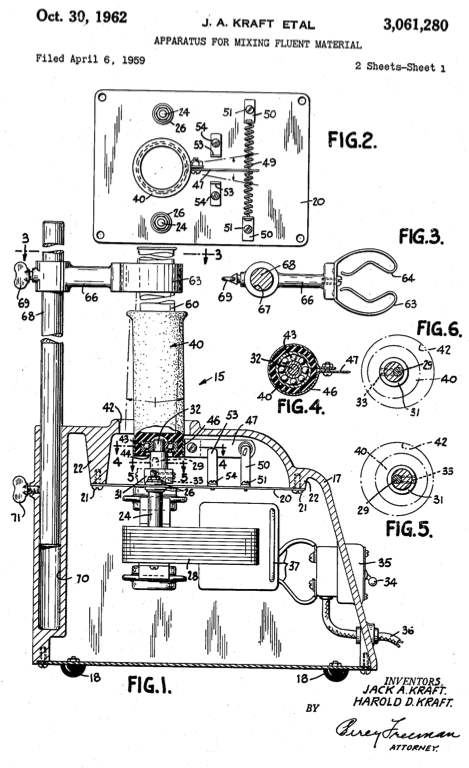

In 1959, a pair of enterprising brothers, Jack and Harold Kraft, filed a patent titled “Apparatus for mixing fluent material.” Though simple in concept, their invention solved one of the most fundamental challenges faced by mid-century scientists: mixing fluids quickly and efficiently. The vortex mixer, a small motorized device that vibrated samples, offered the perfect solution, and is now found on biology benches across the world.

Harold and Jack Kraft were born in New York in the tumultuous years following World War I. From a young age, the boys displayed an entrepreneurial spirit and were always in business together. During the Great Depression, they made money by repairing broken radios and installing radio antennas on buildings in New York City. Family members recall Harold as the gregarious talker or salesman, while Jack led the technical side of their ventures.

Even World War II could not stop their abiding passion for motors and machines. Jack attended NYU School of Engineering while in the reserves, and Harold became an aircraft mechanic in the 519th Service Squadron, working at airfields in England and later France. After the war, the brothers reunited to take up business once again, this time manufacturing their own eponymous brand of Kraftone record players.

By the late 50s, looking to break into scientific equipment, Jack reached out to fellow NYU alumnus and inventor, Dr. Samuel R. Natelson, a clinical chemist who was the Head of Biochemistry at St. Vincent’s Hospital of New York. Natelson kindly obliged Jack’s request, with the two meeting several times for chemistry demonstrations and discussions of the equipment challenges faced by Natelson and his colleagues.

During one such meeting, Natelson expressed a dire need for better mixing equipment. At the time, chemists had only a few options. If the solution volume was large enough, magnetic stir bars could be placed into the mixing vessel, but that meant they needed a corresponding electromagnetic stir plate upon which to place the solution. Most labs had only a few such plates, if any, so when making multiple solutions, there weren’t enough to go around. The alternative was to stir, shake, or flick the vessel manually.1 These apparatuses all needed cleaning between each use.

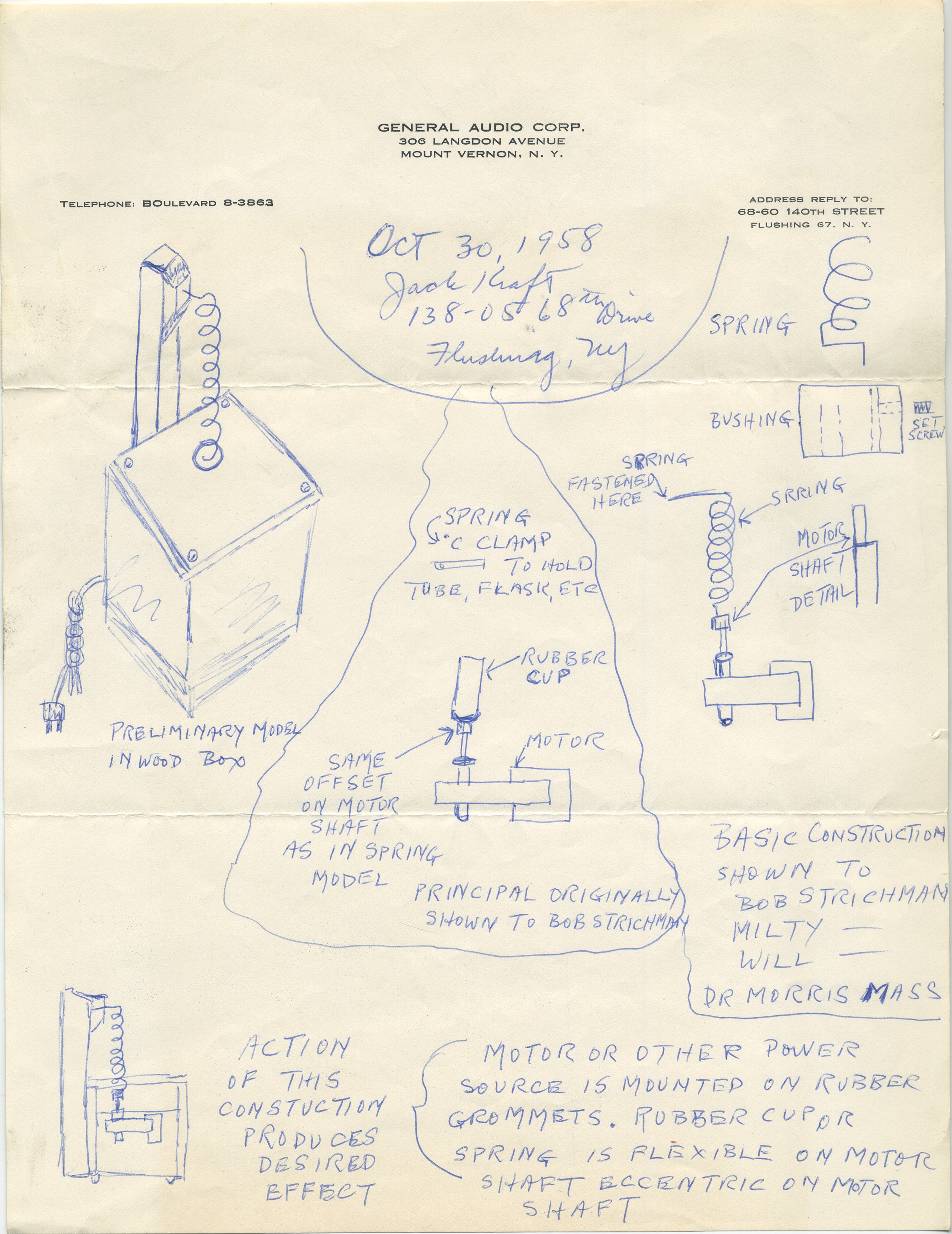

We may never know which specific mixture drew the ire of Natelson. But we can infer from a letter, drafted by the Kraft brothers, that it concerned viscous substances. The letter also reveals just how excited the brothers were about their invention. According to their account, Jack brought the original idea to Harold, and the two sketched out potential solutions on October 20, 1958. Just three days later, they had built their first prototype using the same kind of shaded pole AC motor found in their record players.2

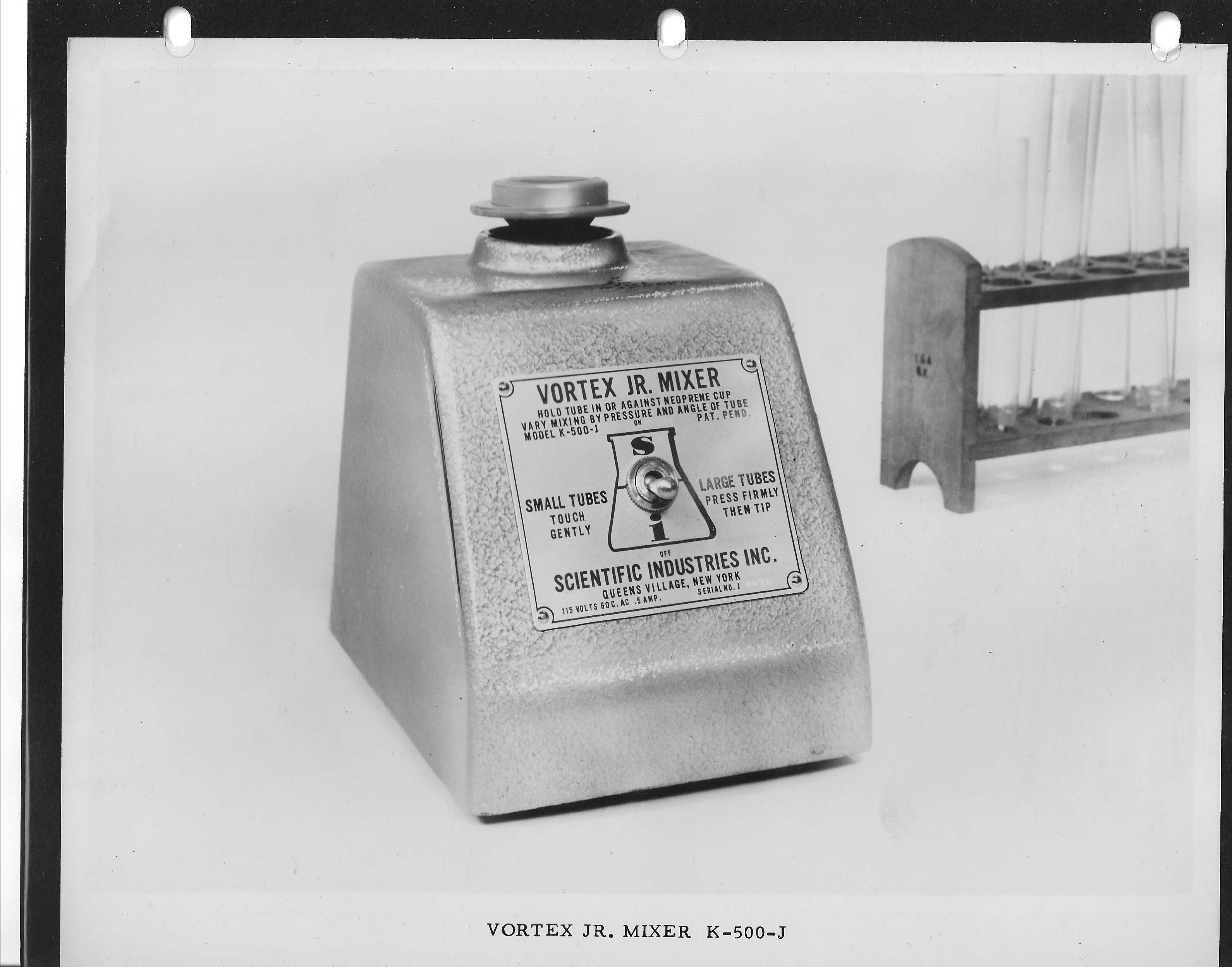

The resulting invention was simple, but elegant. A small, high-powered motor was housed within the body of a box-shaped machine. Mounted atop the motor was a rubber cup. Switched on, the motor oscillated the cup in tight orbital motions. When a test tube, or other vessel, touched the rubber cup, that motion transferred to the liquid, creating a vortex and mixing its contents.

They first demonstrated their invention before a group of scientists at Sunnyside Medical Laboratory in Long Island on October 25th, 1958, just days after building the prototype.3 The vortex was used to wash a protein in water, a step in the protein-bound iodine (PBI) test, a now-antiquated clinical method for measuring thyroid function. The PBI test was regarded as “one of the more complicated and commonly used clinical laboratory tests, requiring skilled technicians and generally requiring a separate laboratory because of contamination problems,” according to a 1967 study. Its several steps traditionally required thorough cleaning of the stirring implements, but each glass stir rod that was introduced increased both the chance of contamination and the potential loss of precious sample material stuck to the glass. A mixing method that didn’t require constant touching of the sample would be valuable indeed.

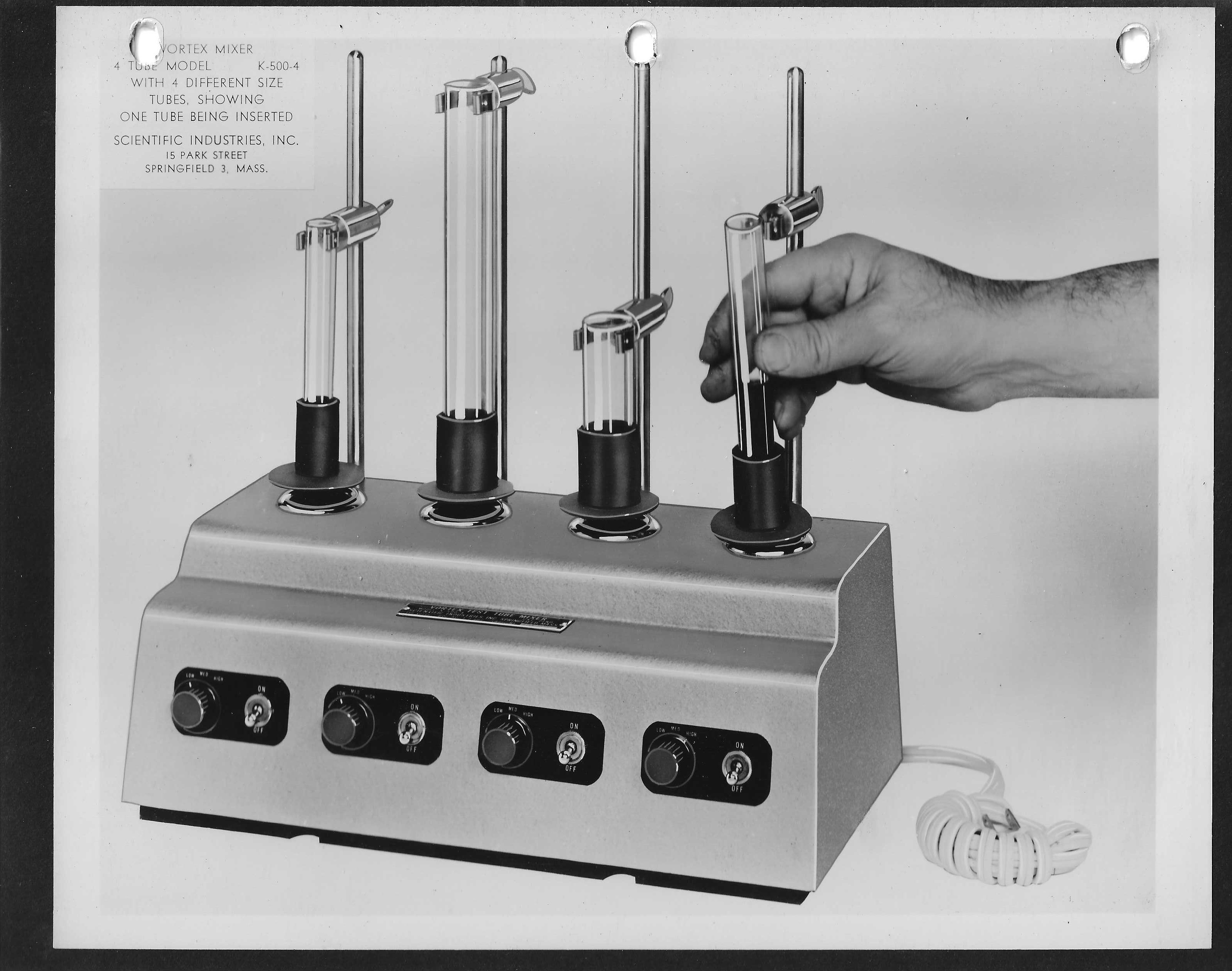

The patent, which Harold and Jack filed on April 6th, 1959, was granted on October 30, 1962. During this time, the brothers were not idle. They began to work with Scientific Industries Inc., a scientific equipment company established in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1954. Harold became its president and Jack its treasurer, and the two moved the company to Queens Village, New York. Scientific Industries Inc. began manufacturing and selling the Kraft brothers’ vortexer in 1962. The very first model was named the Vortex Jr. Mixer. The company also experimented with other form factors and head attachments, like the K-500-4 model, able to mix four tubes simultaneously.

The Kraft brothers also continued tinkering, filing a number of patents by themselves and with Scientific Industries for devices such as the “Rotary apparatus for agitating fluids,” which revolves tubes in a Ferris wheel-like motion to continuously stir them. This tube rotator, though lesser known than the mighty vortexer, is also a common laboratory tool today.

In April of 1965, Harold and Jack left Scientific Industries to found their own scientific instrument manufacturing business, Kraft Apparatus Inc., in Mineola, New York. They continued to refine the design of the vortexer, adding a pressure-sensitive “touch” feature that turned the device on when the rubber cup was pressed down, as well as speed and pulse settings. Finally, in 1982, the Kraft Brothers sold Kraft Apparatus to Glas-Col, a division of Templeton Coal, which still sells vortexers today. Meanwhile, Scientific Industries continued to manufacture its own versions, creating the iconic “Vortex Genie” line.4

Today, scientists commonly use vortexers to mix volumes ranging from microliters to milliliters, most often in plastic Eppendorf or conical tubes.5 As scientific instruments go, vortex mixers are on the sturdy side, weighing in at 4 kilograms, or 8.8 pounds. Their heft and rubber feet provide stability, preventing them from vibrating off the bench. And although newer versions are slightly quieter, older ones emit a distinctive rumble that can be heard echoing throughout the lab.

Vortex mixers also come in a variety of shapes and sizes.6 There are versions that secure 96-well plates or Eppendorf tubes for hands-free mixing. Some have adjustable speed, orbital direction, and digital timers to make mixing more precise.

We owe much to the industrious Kraft brothers, for although the vortex mixer is relatively humble and was created in a span of just three days, its importance is hard to overstate: making mixing, one of the most essential but tedious laboratory chores, easy.

{{signup}}

{{divider}}

Ella Watkins-Dulaney is a bioengineer who owes a not-insignificant portion of her PhD to the vortexer. She is also the Art Director for Asimov Press.

Acknowledgements: Thank you to Howard J., Randy E., Robert, and Ruth Kraft for their interviews about Kraft family history. A special thank you to Scott Kraft for all of his work collecting historical documents and helping me piece together this story. It would not have been possible without you. And thank you to Xander Balwit as well for the consistent editing and support.

Cite: Watkins-Dulaney, E. “Making the Vortex Mixer.” Asimov Press (2026). DOI: 10.62211/49jq-97pk

Footnotes

- How vigorously the vessel was agitated depended on the size of the vessel and volume to be mixed. For example, a separatory funnel might be held in two hands and shaken up and down, while a test tube could be held in one hand and flicked at the bottom to produce a vortex-like motion.

- The letter and accompanying invention sketches that were made on their lawyers letterhead, dated October 30th, were presumably to document the invention for patenting.

- In their concept sketches, Milton and Will were affectionately referred to only by their first names (“Milty” and “Will”), so it is assumed that the brothers had a closer personal relationship with this group than with Natelson.

- The Genie Line was acquired by OHAUS Corporation in 2025.

- Volumes under 100 microliters are more practical to mix with a pipette. For volumes larger than a few hundred milliliters, it is more practical to use a magnetic stir bar.

- The patents for the original vortex expired in 1979, and most derivative patents have expired as well.

Always free. No ads. Richly storied.

Always free. No ads. Richly storied.

Always free. No ads. Richly storied.