Scent, In Silico

Smell is our most primal and, arguably, most emotionally potent sense. It summons memories, shapes taste, and influences behavior: the aroma of coffee is capable of enhancing alertness well before caffeine ever reaches the bloodstream. A hint of sunscreen collapses decades, taking us back to youth; but, pinch the nose, and suddenly a slice of apple is hard to distinguish from a piece of raw potato.

Despite its significance, scent remains the most mysterious of our senses. Unlike vision or hearing, it resists straightforward formalization. The challenge lies not only in the vast molecular diversity of odorants, which vary in far more ways than photons or frequencies, but also in the effort to build a shared vocabulary and technology capable of codifying subjective sensation. So while machines have learned to see through computer vision and hear through signal processing, scent remains stubbornly analog. There has been no RGB of odor, no Fourier transform for smell.

At least, until now.

Tech giants, including Google, startups such as Osmo, and even traditional fragrance houses like Givaudan have begun turning to AI to probe the possibility of digitizing smell. By encoding scent molecules into 1s and 0s, their hope is to better understand and manipulate this sensory modality. Just as “computer vision” has helped us realize that sight is not just passive image capture but an active process of prediction and interpretation, researchers hope that programming smell will illuminate the many mysteries of olfaction.

Beyond providing further insight into olfactory biology, digital scent could have many practical (and quite profitable) applications, which is why its proponents, from defense agencies such as DARPA to corporate conglomerates like Estée Lauder, have invested in it. Computational smell could, for example, help detect threats and information invisible to cameras, such as gas leaks, food spoilage, disease markers in breath, and even counterfeit products. It could also reduce reliance on resource-intensive natural ingredients used in perfume and other odorants by, for instance, finding chemically synthesized molecules capable of evoking the same brain patterns. And finally, it could lead to the creation of entirely novel smells, revealing a vast, untapped chemical palette that would otherwise be unattainable without the aid of technology.

{{signup}}

The Bacterial Beginnings of Smell

Long before life evolved eyes and ears, the world was encountered chemically. This took place as molecules permeated and diffused across cell membranes, performing a metabolic exchange between animate and inanimate matter.

Smell, our most ancient interface with the environment, originated over 3 billion years ago, in bacteria adrift in the primordial ocean. These early organisms navigated chemical gradients in the water, detecting molecules to swim toward food and away from danger. This ability, known as chemosensation, is the most rudimentary form of smell.

Such “sensing” relies on receptor proteins embedded in the cell membrane, acting like molecular locks awaiting the corresponding chemical key. When a passing odor molecule fits into a receptor’s binding site, it changes the receptor’s shape, setting off a cascade of signals inside the cell that direct the organism’s movement.

Over time, these molecules didn’t just guide survival; they encouraged multicellular life. As cells began clustering together, the exchange of semiochemicals — molecular signals that transmit information within and between species — began to influence behavior, enabling aggregation and synchronization, and laying the groundwork for cellular cooperation. Plants, for instance, release green leaf volatiles such as cis-3-hexenal (the familiar scent of freshly cut grass) when attacked, both warning neighboring plants and attracting the animals that prey on herbivores. Human infants, meanwhile, are drawn to the distinctive odor of their mother’s milk, which both stimulates feeding and regulates their earliest physiological rhythms. And among insects, ants are famous for deploying pheromones such as iridodials, which direct entire colonies to forage or fight in concert.

Once the first tetrapods emerged from the sea and embraced life on land, smelling evolved to become ever more refined under newfound terrestrial pressures, including adapting to novel volatile odorants and the more variable conditions of airborne climates. As these early terrestrial vertebrates expanded a chemosensory repertoire that had once been far more limited in their aquatic ancestors, olfactory systems likewise continued to evolve. Over the next hundreds of millions of years, the neural structures supporting our own sense of smell increased in sophistication.

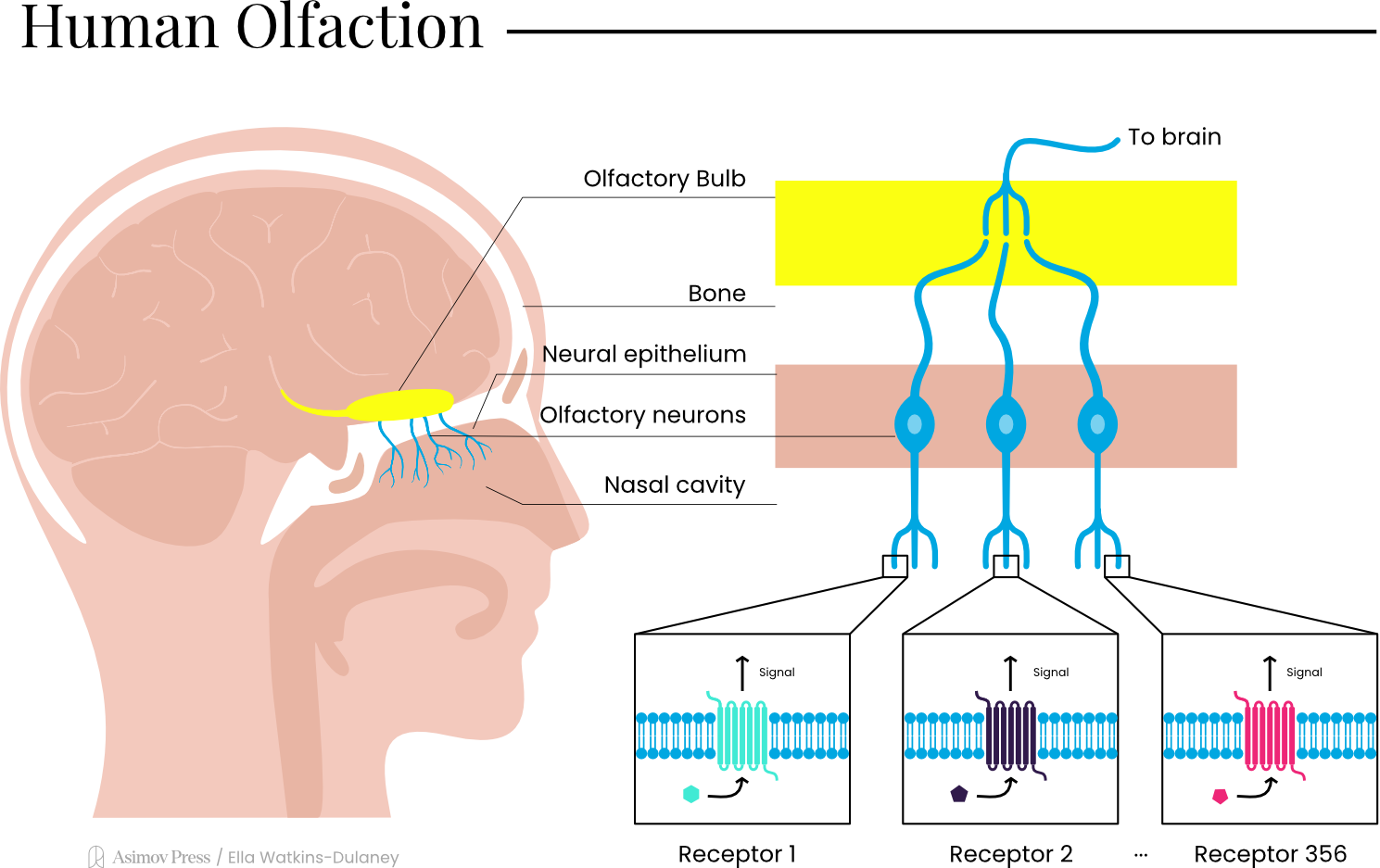

Today, roughly two to five percent of our genetic blueprint concerns itself with smell. While it may seem a small fraction of the whole, it is the largest gene family in the human genome. At any given time, 77 percent of the 356 distinct olfactory receptors are expressed in the lining of the nasal cavity, each tuned to the molecules that make up the world’s myriad smells. The receptors expressed vary between individuals, with only 90 receptors commonly found in all people. Together, this suite of receptors is responsible for every experience of scent we encounter, and the variability between individuals is likely behind smells’ subjectivity.

To understand how this olfactory complexity works, consider the single inhalation that follows biting into a ripe strawberry: the rush of aroma, the sweet, tangy burst blooming in the nose, created not by a single compound but by a volatile molecular cocktail. There is no one single molecule responsible for the smell of strawberry, but rather a family — namely furaneol (caramel-sweet), methyl and ethyl butanoate (fruity), methyl 2-propanoate (fruity), hexanal (green and sharp), and cis-3-hexenol (leafy-fresh) — that evaporate and surge through the nasal cavity.

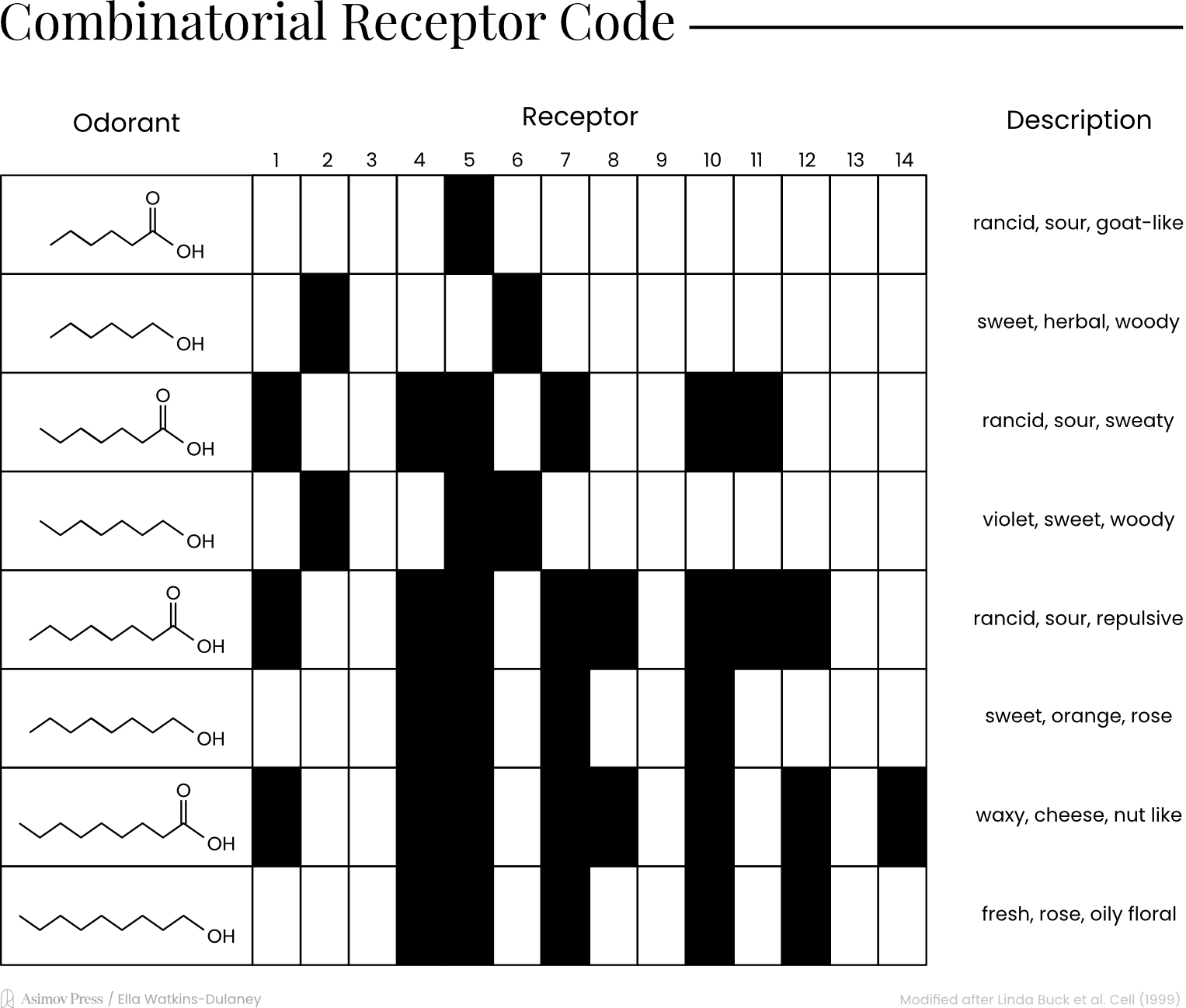

In each nostril, this medley of molecules dissolves into the mucus layer lining a 2.5 cm² patch of tissue known as the olfactory epithelium. Studded across this small region is a mosaic of roughly 10 million olfactory sensory neurons,1 each expressing only one type of olfactory receptor protein. In one breath, an odorant molecule, be it furaneol, cis-3-hexenol, or any other, activates a unique combination of receptors, similar to striking a subset of keys on a piano. This ensemble of activated neurons forms a distinct pattern that the brain reads as “strawberry.”

Crucially, no two scents ever strike the same pattern. The combinatorial activity of hundreds of receptor genes allows humans to detect and discern more than a trillion distinct odors.

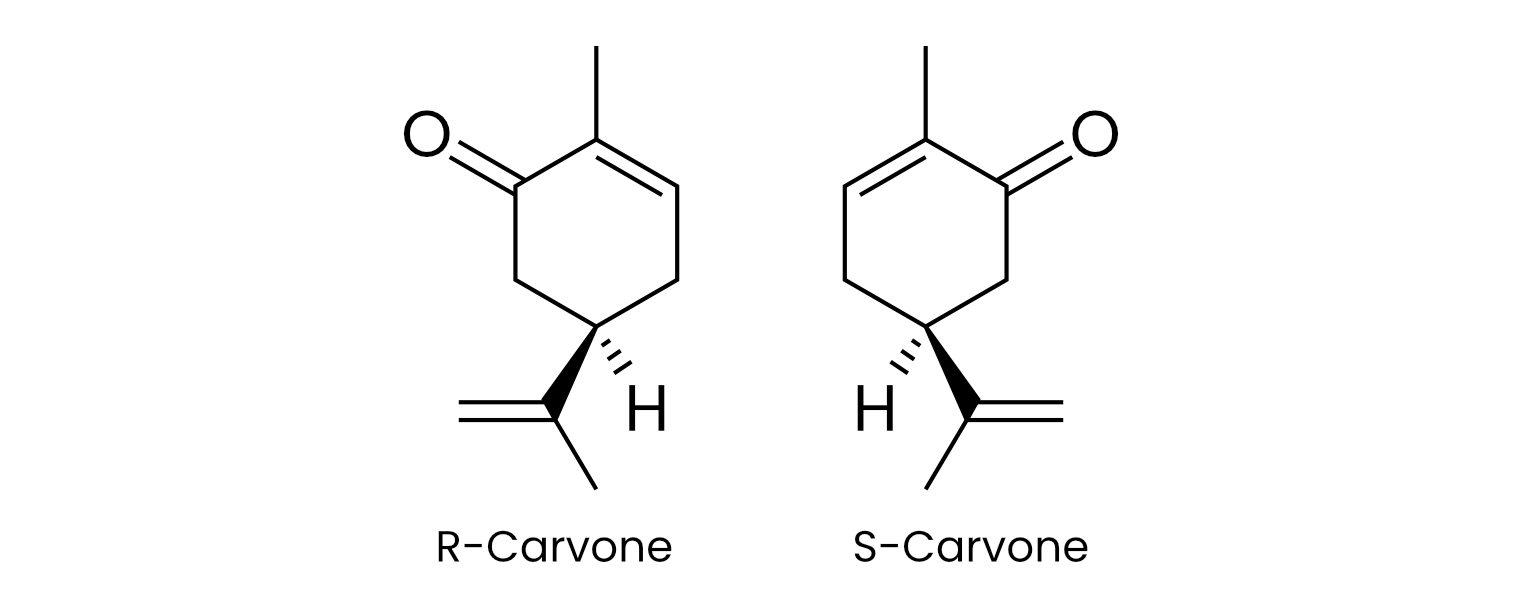

While some olfactory receptors respond broadly, meaning they can recognize and bind to several different structurally-related molecules, other receptors are exquisitely selective and bind to only one specific shape or stereoisomer.2 For instance, the two mirror-twin forms of the organic compound carvone smell strikingly different — one like spearmint (R-carvone), the other like caraway (S-carvone) — underscoring the nuance the nose brings to discriminating between such molecular mirror images.

The resultant signal, whether “caraway,” “spearmint,” or “strawberry,” travels to the olfactory bulb, a bipartite nerve structure nestled at the base of the skull, just above the nasal passages. There, neurons expressing the same receptor type converge on specialized structures called glomeruli, the crucial processing hubs that sharpen and refine sensory input en route to deeper regions of the brain involved in odor discrimination.

Each glomerulus acts as a dedicated module for a single receptor type, receiving input from thousands of olfactory sensory neurons scattered throughout the nasal epithelium, but all tuned to the same molecular features. Within these spherical tangles of neural connections, the incoming signals undergo their first round of processing: they’re amplified, filtered, and integrated by local interneurons that enhance contrast between different odor signals.

Unlike other senses, these olfactory signals take an unusual route through the brain. While vision, hearing, and touch all pass through a brain region called the thalamus before reaching higher brain regions, smell bypasses this checkpoint. Instead, odor information travels directly from the olfactory bulb to the amygdala and hippocampus (two brain structures central to emotion and memory) before reaching conscious processing areas. This anatomical shortcut may explain why smells can trigger vivid memories and strong emotions before we’ve even consciously identified what we’re smelling.

Yet, while the nose has been anatomically mapped, receptors sequenced, and neural pathways charted, predicting a molecule’s scent has remained a mysterious exercise. The question of why certain configurations of matter smell one way and not another persists. In other words, why does a molecule such as furaneol activate the receptor signaling “jammy sweetness”? What makes one molecule smell “grassy” and another “creamy,” one trigger nausea and another nostalgia?

The prevailing hypothesis defines odorant molecules as ligands, specialized binding molecules that fit into olfactory receptors like a lock and key. This interaction activates the receptor, initiating an electrical response in the brain, a unique pattern of activity associated with a particular scent. While molecular structure has long served as a proxy for predicting smell, particularly for researchers and fragrance chemists, the so-called Structure-Odor Relationship (SOR) paradox endures: molecules of nearly identical structure can smell worlds apart, while those with little in common can smell strikingly similar.

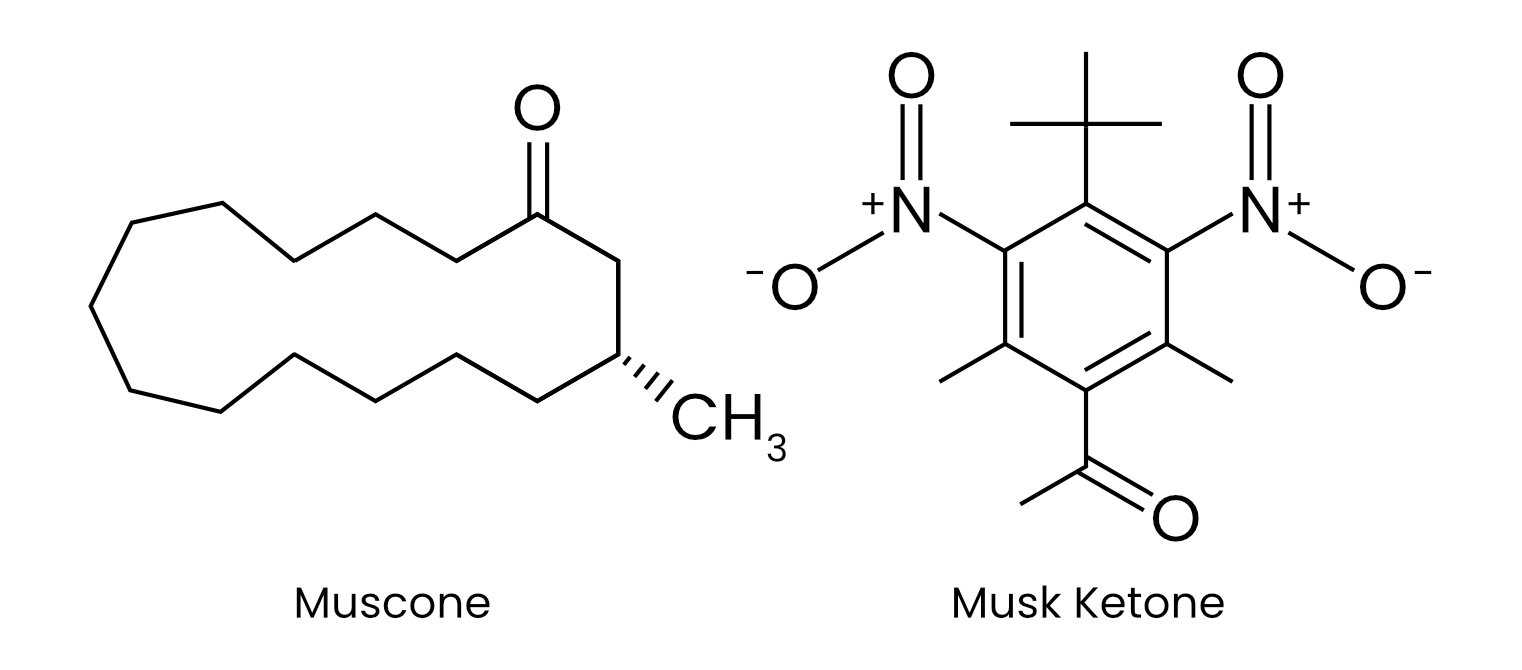

Take musks,3 for instance: this family of compounds includes hundreds of molecules with vastly different structures and molecular weights, ranging from small macrocycles to large polycyclic frameworks. Yet, despite this diversity, many share a common warm, powdery, and animalic scent profile that defies straightforward structure-to-smell prediction.

An Industry for Smell

The speculation that chemical structure corresponds to scent dates back millennia, alongside the use of fragrant materials in ceremonial and cultural practice. From the early Greek atomists’ theories of microscopic films emitted by objects to excite the senses, to the incense artisans of ancient Egypt and East Asia, humans have long sought to capture and understand the elusive nature of smell.

Before the emergence of more sophisticated means for extracting and preserving scent, fragrance was elicited through rudimentary methods such as crushing raw botanicals, steeping them in oils, or burning resins to release their aroma.

During the eighth and ninth centuries, the invention of the “modern” alembic — a distillation apparatus developed by Islamic alchemists featuring a still pot, a cooling condenser, and a collection spout — allowed for a more controlled extraction of delicate essential oils than crude crushing or simple heating could achieve. This innovation enabled new forms of fragrance production, introducing alcohol as a base and associating the practice of perfumery more closely with chemistry and medicine. Through trade and translation, this technology and technique migrated to continental Europe, where perfumers expanded their repertoire over centuries with methods such as maceration, expression, tincturing, and enfleurage4 to isolate the volatile compounds of flowers and woods.

In the sixteenth century, tanners making leather gloves sought to mask the acrid smell of their wares with fragrant oils and extracts. Scented gloves quickly became fashionable among the European aristocracy, and perfumers found a lucrative market beyond functional necessity. At Versailles, the epicenter of French culture and seat of royal power, courtly fashion demanded a complete sensory presentation: the right clothing, hairstyles, cosmetics, and an ever-changing repertoire of perfumed products to signal refinement and status.

This high consumption of scent supported a nascent perfume industry, formalized in 1656 in Grasse, France, with the creation of the Maîtres Parfumeurs et Gantier (the perfume and glove-maker’s guild). Alongside its favorable social-political milieu, Grasse’s microclimate fostered a burgeoning perfume industry in the region, where fertile soils nurtured fragrant flowers such as jasmine, rose, lavender, orange blossom, myrtle, mimosa, and tuberose. This economic activity, along with the formation of local perfume, helped establish France’s perfumeries as centers of both craft innovation and the formal study of smell.

The nineteenth century marked a decisive shift as techniques from pharmacy and organic chemistry began to elucidate molecules underlying fragrance. Building on earlier breakthroughs such as the isolation of morphine in 1804 (the first alkaloid ever extracted from a plant), chemists turned their attention to aromatic materials.

In 1820, the French pharmacist Nicolas Jean Baptiste Gaston Guibourt identified and isolated 2H-chromen-2-one, better known as coumarin, from the tonka bean (Dipteryx odorata). In an account presented to the pharmacy section of the Académie Royale de Médecine, Guibourt formally christened the new substance coumarine, marking one of the earliest instances of the chemical characterization of a fragrance compound. In 1858, another French chemist, Théodore Nicolas Gobley, succeeded in crystallizing vanillin from vanilla pods, confirming that odorants could be identified as discrete molecular entities.

For the first time, individual aromatic molecules — a resonant note of the rose, one iota of the vanilla pod — could be extracted from a larger, complex composition. Smell was being recast as a phenomenon amenable to classification and design.

Driven by advancements in organic chemistry and the introduction of the periodic table in 1869, fragrance chemistry blossomed. By 1882, Paul Parquet’s famous scent, Fougère Royale, featured coumarin, followed by Guerlain’s Jicky in 1889, and in 1921, Chanel No. 5 launched using an entirely new class of synthetic compounds, the aldehydes. The perfume industry eagerly adopted new techniques, including chromatography and fractional distillation.

Driven by advancements in organic chemistry and the introduction of the periodic table in 1869, fragrance chemistry blossomed. By 1882, Paul Parquet’s famous scent, Fougère Royale, featured coumarin, followed by Guerlain’s Jicky in 1889, and in 1921, Chanel No. 5 launched using an entirely new class of synthetic compounds, the aldehydes. The perfume industry eagerly adopted new techniques, including chromatography and fractional distillation.

As the twentieth century unfolded, scientists intensified their quest for structural correlates of scent. Discoveries like ionone-related ketones evoking violet and woody notes, long-chain macrocycles recurring in musks, and aromatic rings anchoring vanillic and balsamic tones found their way to the traditional orgue à parfums, a semicircular, horseshoe-shaped work station: a harbinger of what would become a more serious investigation of the science and technology of smell.

Digitizing Smell

Over eons, organisms evolved a sense of smell. In the past three centuries, smell became chemistry. And in recent years, we have started to ask whether smell can become code.

However, unlike sound and color, smell resists straightforward formalization. Color, for instance, has been reduced to three primary channels, standardized through the color wheel, and rendered into numeric systems that machines can interpret. Sound has been decomposed along perceptual axes of pitch, timbre, and amplitude, each capable of digital transformation. Odor, however, has no reliable relationship to molecular structure or perceptual encoding, making it difficult to establish a computational coordinate system.

As a result, early computational efforts in representing molecules were often ad hoc: homemade tables to track atomic bonds, bespoke matrices, or custom linear codes that translated chemical structures into character strings. These methods were clever but small-scale and subjective, making calculations laborious and difficult to reproduce.

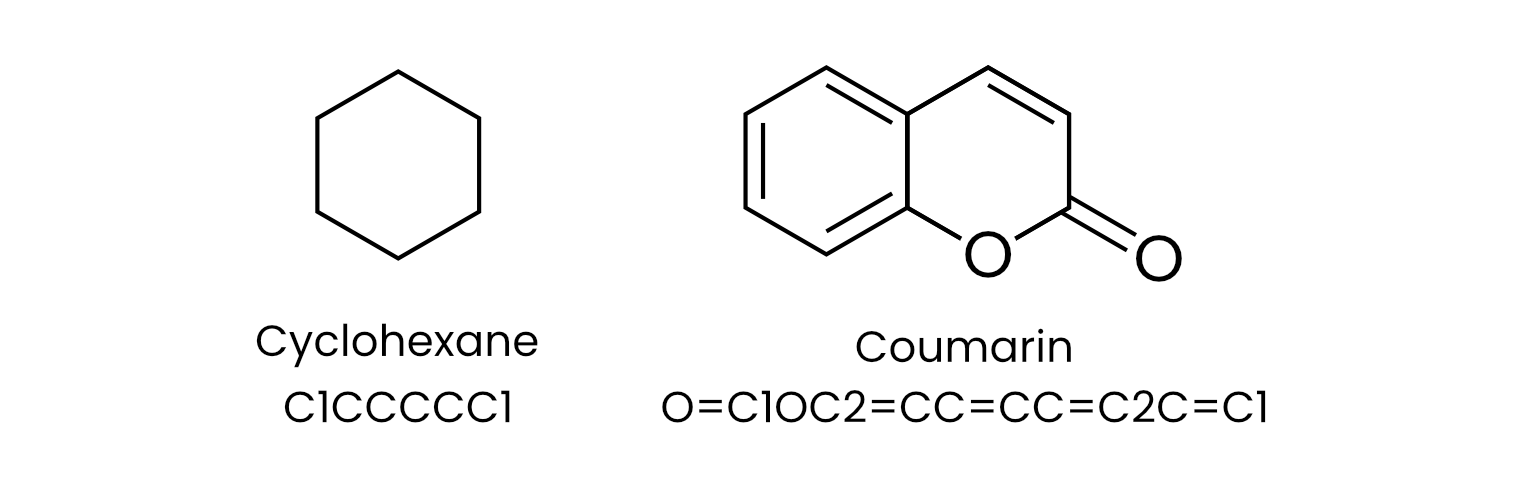

Then, in 1988, while at Pomona College in Claremont, California, chemist David Weininger devised SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System). SMILES provided a standardized, machine-readable line notation for encoding molecular structures. Like any language, SMILES is a formal system for representing information; in the context of chemistry, it acts like a cipher or code to translate molecular structures into linear character strings. A given molecule, according to convention, is spelled out as a word or a particular grammatical grouping of letters, where each letter corresponds to an individual atom. Contained in each word is also the logic for how certain letters connect or are arranged geometrically, including instructions for branching and ring closures. For instance, the six-carbon ring cyclohexane is represented by slicing open the ring and labeling the adjacent atoms with matching numbers to indicate connection and closure: C1CCCCC1. In the same fashion, coumarin can be written as O=C1OC2=CC=CC=C2C=C1.

In practice, however, this descriptor-based model could not contend with the idiosyncratic nature of the structure-to-odor relationship: a molecule may be classified as citrus-like by virtue of its ester group, while a structurally analogous compound with only minor modifications might be seen as sharp, metallic, or entirely odorless.

As academic labs continued researching the logic of scent, focus shifted toward building larger datasets that linked molecular structure to qualitative descriptions of odor perception. In place of binary quantifiers such as odorous/odorless or pleasant/unpleasant, these collections captured distinct attributes like fruity, floral, musky, or burnt, offering a more embodied and qualitative relationship between chemistry and experience.

Democratizing databases such as the Good Scents Company, for example, expanded the vocabulary of olfaction available for computation, priming the field for machine learning approaches capable of finding patterns across large, multidimensional datasets.

In 2015, IBM Research and Rockefeller University launched the DREAM Olfaction Prediction Challenge, the first large-scale, open benchmark for predicting human olfactory perception from the physicochemical features of odor molecules. Researchers were provided with data comprising 476 chemically diverse odorants, each described by over 4,800 molecular features and rated by 49 human participants on 19 sensory attributes, such as sweet, fish, mint, and sour.

Competing teams trained machine-learning models to map feature-perception relationships and evaluated their models using 69 unseen test molecules. The top models achieved prediction measures comparable to those observed among human participants, meaning the machine ratings were nearly as reliable as human noses when judging whether a chemical smelled floral or fishy. The models’ predictions mirrored the average agreement reported in human odor-perception ratings, demonstrating accuracy of up to 85 percent across multiple different aromas.

Although the DREAM challenge yielded compelling evidence that odor perception could be forecasted computationally, it had its shortcomings. Namely, the study’s dataset remained modest in scale, leaving vast chemical territories uncharted, and its reliance on predefined molecular descriptors meant the models depended on prescribed features rather than uncovering the latent logic linking structure to odor.

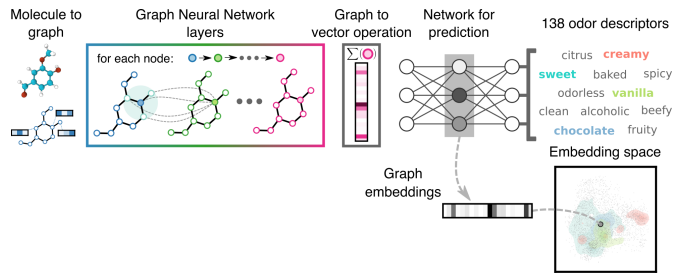

By 2019, researchers at Google Brain (now DeepMind) sought to overcome these constraints by expanding both the scale of training data and the fidelity of their model. Using deep learning and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), a class of models that interpret molecules as graphs with atoms and bonds represented as nodes and edges, respectively, the study employed a dataset containing more than 5,000 odorants annotated by expert perfumers across over 100 descriptors, from mint and potato to sulfurous and grassy.

Unlike the earlier DREAM Challenge, which relied on prescribed molecular features, such as atom counts and topological indices, this approach allowed the model to infer structure-odor relationships directly from data. To initiate the training process, each node (representing an atom) was seeded with basic chemical information, including atomic number, valence, hybridization, and formal charge.

Through a recursive process known as “message passing,” the state of each atom was repeatedly updated in response to information relayed by neighboring nodes. Layer by layer, the model built up a progressively bigger picture of a molecule: early layers learned to identify local features like carbonyls, halides, or ring systems, while deeper layers learned to recognize broader chemical motifs such as aromaticity, conjugation (the overlap of p-orbitals), and steric strain (the increase in potential energy of a molecule due to repulsion between electrons in atoms that are not directly bonded to each other).

By the penultimate layer, the complete, networked “picture” of a molecule was condensed into a fixed-length, 63-dimensional vector, known as an “odor embedding,” capturing the molecule’s perceptual qualities in a computable form. This embedding was then used for classification tasks, such as predicting specific odor descriptors or categorizing the molecule’s scent profile.

When these “images” were compressed, molecules that smelled alike clustered together even when their chemical scaffolds were structurally dissimilar. For example, certain esters and ketones, molecules that share little in common structurally, appeared close in this space because both carried a sweet, fruity scent, while structurally related compounds could be separated if their perceived odors diverged. This act of compression thus exposed a “geometry of smell.”

It also laid the groundwork for Google’s subsequent introduction of the Principal Odor Map (POM): the first map of smell, in which traversing through space corresponds to crossing distinct regions of aroma, from jasmine to potato. Building on the previous study, the researchers expanded the model’s embedding layer by 193 dimensions, creating a high-dimensional coordinate system that positions each odorous molecule as a single point within a continuous manifold (e.g., a connected shape or space that behaves geometrically, enabling meaningful comparison and relation between the position of points representing molecules). In this space, perceptually similar odors occupy nearby positions, much as blue lies closer to turquoise than to crimson on the color wheel, while increasingly dissimilar ones are separated by greater distance.

When the researchers subjected the POM to further tests, they found that it could generalize beyond human olfactory perception, predicting olfactory receptor activity across species from mice to insects. This cross-species application suggests that the model’s internal structure even captures evolutionary principles of scent. On the map itself, metabolically related compounds — those separated by only a few metabolic reactions or naturally co-occurring in the same substance — also occupy nearby coordinates, forming concentrated clusters that reflect their shared chemical and perceptual relationships.

By capturing such subtle perceptual relationships, the model not only surpassed traditional chemoinformatic algorithms in terms of predictive accuracy, but also enabled early steps toward the design of new odorants.

Building on this foundation, Osmo, a start-up spun out of Google Research in 2022, has begun leveraging its proprietary Olfactory Intelligence (OI) platform informed by POM to translate sensory scent data into chemical design. The company’s goal is to “give computers a sense of smell.”

Glossine, Fractaline, and Quasarine are the first prompt-generated fragrance molecules created using its platform. According to the company, Glossine delivers a “Las Vegas-style sparkle,” with a floral jasmine-like top note that adheres well to textiles; while Fractaline offers a versatile violet note, reputed to give a powdery, “second-skin” impression; and Quasarine presents an intense yet delicate jasmine aroma claimed to deliver a long-lasting “fresh petal-y effect.” While these descriptors could be shared by other perfumes, these fragrances are entirely original. Where traditional perfumery relies on the discovery and refinement of proprietary molecules in a process that usually takes years, Osmo can “create” completely new odorants through this OI platform in just a few days.

The potential applications of Osmo’s OI platform, however, extend far beyond fragrance. Because the Principal Odor Map can extrapolate olfaction across species, Osmo has leveraged it for developing synthetic alternatives to DEET, the active ingredient in most commercial insect repellents, but one which has been linked to adverse effects, including severe skin reactions like rashes and welts. Trained on experimental datasets measuring mosquito repellency, the model can predict the repellent efficacy of nearly any molecule. Experimental validation confirmed over a dozen new molecules as repellent as DEET, but which could offer safer, longer-lasting alternatives for killing mosquitoes and ticks.

Beyond repellents, Osmo has broader ambitions to also develop non-invasive diagnostic tools. They aim, for example, to identify volatile signatures emitted by various diseases, enabling algorithms with a “digital nose” to detect conditions such as Parkinson’s, diabetes, and certain cancers through subtle changes in body odor or sebum, a type of signal detectable by dogs.

Perhaps the most promising application of Osmo’s technology, though, relates to sustainability. By synthetically generating fragrance molecules, Osmo offers a path toward decreasing the environmental impact of industrial scent-production. A canonical and increasingly endangered raw material for scents is rose, whose odor has captivated humans for millennia yet remains one of the most labor-intensive and expensive natural ingredients (some 60,000 roses, roughly 180 kilograms of petals, are required to produce a single ounce of oil, which sells for $8,000 to $12,000 per kilogram). By plotting the scent of Rosa damascena and Rosa centifolia on the POM, Osmo can work toward “reverse-engineering” the rose and other floral notes in pursuit of designing “an alternate universe of perfume ingredients” that are perceived similarly without requiring raw botanical sources.

Osmo is not alone in its effort to advance computationally mediated scent. Givaudan’s Carto, the digital design platform of one of the world’s first and largest fragrance houses, is also using computer technology to design its perfumes. Carto integrates predictive algorithms with a database of over 5,000 raw materials (five times more than a human perfumer typically manages) to help perfumers simulate, match, and modify scents. Whereas the classical perfume orgue à parfums once arranged rows of essences within arm’s reach, Carto replaces physical glass vials with a virtual glass touchscreen display. The platform was used to formulate Tom Ford’s Bois Pacifique, which launched in January 2025.

Despite such recent successes, the mysteries of olfaction are far from solved. To digitize the scent of a rose, for instance, requires contending with over 300 volatile compounds that contribute to its spicy, honeyed, and tea-like notes. These compounds are not simply additive but dynamic; their interactions, relative concentrations, and release create emergent qualities unpredictable from any single component alone. While platforms like Osmo and Carto can tinker with individual molecules, capturing the interplay of dozens or hundreds of odorants in a given mixture remains a formidable challenge, the mastery of which will be next in digitizing smell.

Both industry and academia continue to advance this aim. The most recent DREAM Olfaction Challenge, slated to close in late 2025, tasked international teams with predicting perceptual similarity across volatile mixtures. It will draw on a dataset of over 700 combinations containing anywhere from two to ten different molecules to assess how accurately teams can digitally model smells, their interactions, and their resulting impressions. Although peer-reviewed results have not yet been published, early findings point toward improvements in complex-mixture scent prediction.

The Future of Olfaction

Traditionally, the fragrance industry has made a point of drawing a line between the natural and the synthetic, with the introduction of synthetic scent molecules in the mid-nineteenth century garnering both criticism and celebration. Early critics5 proclaimed such synthetic materials as “vulgar debasements” of perfumery, reflecting anxieties surrounding industrialization and the loss of heritage and craftsmanship. But others celebrated this innovation. Guerlain’s Jicky (1889), for instance, which incorporated synthetic vanillin and coumarin, was hailed as a new chapter for perfume. Moreover, commercial houses like Lubin marketed synthetic musks as “triumphs of science … over Nature,” promoting the “non-evanescence” (long-lasting) qualities of synthetic chemicals in comparison to natural ingredients.

These developments unfolded within a wider cultural moment that the essayist Max Beerbohm described as “a new epoch of artifice.” The emergence of synthetics did not simply replace the natural; it upset the very idea of what “naturalness” meant — did it refer to an ingredient’s source, its sensory impression, or the meanings attached to it?

Even today, materials such as ambergris (a waxy, sweet-smelling substance formed in the digestive system of sperm whales and expelled into the ocean) remain highly coveted precisely because of their scarcity and natural origins. Revered as “the treasure of the sea,” ambergris is found in less than five percent of sperm whales and develops its celebrated complexity over years of exposure to sea, salt, and sun. Such a valued ingredient commands reverence precisely because of its rarity, exposing how ideas of purity and authenticity continue to shape our perception and appreciation. Ultimately, the persisting popularity of ingredients such as ambergris demonstrates that value pertains as much to culture as to chemistry, reflecting not only the reality of raw materials but also the moral and aesthetic weight we ascribe to their provenance.

Given this legacy, how might we relate to machine-generated molecules?

The shift to digitized scent will require that we rethink not only the substances themselves, but also the stories we tell as we find ways to valorize their synthetic origins. Such computationally-designed scents are, after all, safer, allergen-friendly formulations compliant with evolving regulations. Furthermore, AI-designed aromas often use more sustainably produced molecules, with a lab-created civetone replacing wild civet extract (a substance associated with the questionable practice of keeping civet cats in captivity for their perineal gland secretions).

A similar parallel has played out elsewhere: a one-carat lab-grown diamond, while chemically and optically identical to a mined one, can cost less than a quarter of the price, despite being purer and more ethically produced. While they have been derided as “costume jewelry,” the market for lab-grown diamonds was valued at $18.91 billion in 2023 and is expected to double by the 2030s. The connotations of luxury are increasingly leaning toward narratives of sustainable and ethical sourcing.

Machine-imagined scents may follow a similar arc. But just as the telescope widened our aperture to distant cosmic structures, digitally composed scents will expand our olfactory range, this time towards the smallest scales of chemical configuration.

{{signup}}

{{divider}}

Taylor Rayne holds a degree in biochemistry and computer science, as well as a deep curiosity for the interplay between scientific and cultural production. She currently works at the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Biosustainability, based at the Technical University of Denmark.

A special thanks to Christiana Agapakis for her generosity and resources; Jasmina Aganovic for her thoughtful guidance and time; Xander Balwit for her steady editorial support, and of course, Astrid.

Cite: Rayne, T. “Scent, In Silico.” Asimov Press (2026). DOI: 10.62211/28jw-12ty

Footnotes

- Humans have ~20 million sensory neurons in total. The exact size, location, and neuron density of the olfactory epithelium varies by individual and can change based on factors like age, exposure to airborne hazards, or disease.

- A stereoisomer is a molecule composed and connected via the same atoms as another, but with a different three-dimensional structure.

- In the perfume business, musks are prized for their sensuality and longevity. They vary extraordinarily in chemical structure and source. Traditional musks include Moschus moschiferus from the abdominal gland of the male musk deer, civet from the perineal glands of the African civet cat, castoreum from the castor sacs of beavers, and ambergris from sperm whales. But natural musks are also costly, difficult to source, and fraught with ecological and ethical concerns, spurring the search for synthetic alternatives. In 1888, Albert Baur discovered the first synthetic “nitro-musk” while working with TNT, soon developing compounds such as musk ketone, musk xylene, and musk ambrette, today used in perfumes including Chanel No. 5. These nitro-musks were later banned due to toxicity and instability, replaced by safer, synthetic musks.

- Enfleurage is a centuries-old perfume extraction technique used for delicate flowers like jasmine and tuberose that are too fragile for heat-based methods. Fresh petals are laid onto glass plates coated with purified animal fat — typically odorless lard or tallow — which absorbs the flowers’ volatile aromatic compounds over one to three days. The spent petals are removed and replaced with fresh ones, a process repeated for weeks until the fat becomes saturated with fragrance, creating a pomade. This pomade is then washed with alcohol to dissolve out the concentrated perfume oils; once the alcohol evaporates, what remains is an “absolute” — the purest essence of the flower. Though largely abandoned today due to its labor-intensiveness, enfleurage once produced some of perfumery’s most exquisite and faithful floral scents.

- Eugénie Briot, La Fabrique des parfums – Naissance d’une industrie de luxe. As France has historically been central to the development of perfumery, this French-language source provides a detailed account of early critics’ reactions to synthetic materials and the broader tensions between industrialization and artisanal craftsmanship.

Always free. No ads. Richly storied.

Always free. No ads. Richly storied.

Always free. No ads. Richly storied.