How Nature Became a 'Prestige' Journal

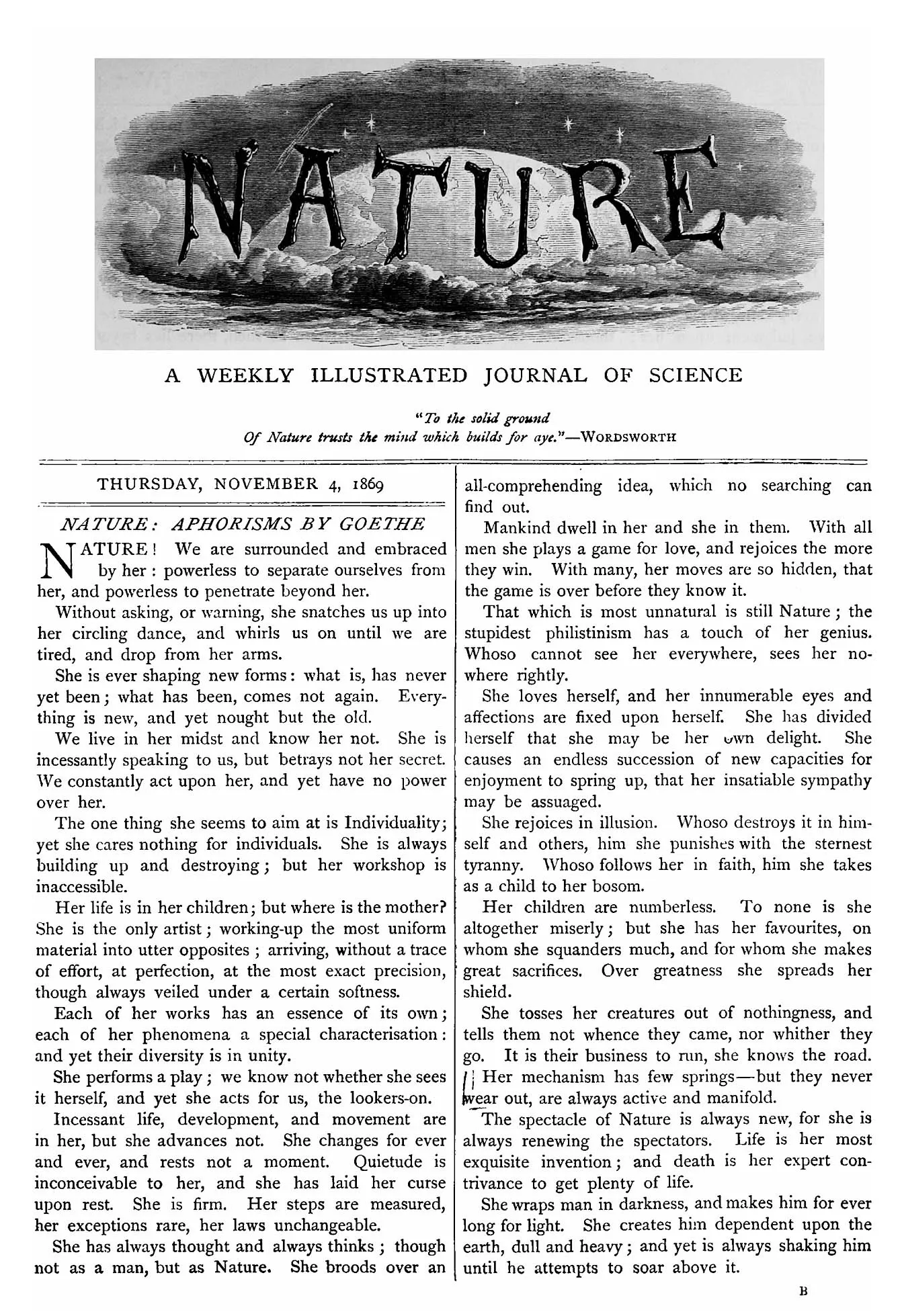

Science seeks truths that outlive those who discover them. English poet William Wordsworth’s observation that “to the solid ground of nature trusts the Mind that builds for aye [forever]” — a line that appeared beneath the masthead of the scientific journal Nature for 75 years — captures this romantic ambition: the dream that building on nature’s foundations yields truths durable enough to transcend their discoverers.

And yet, for many of us, when we think about scientific prestige, we cannot help but focus on the individual. Often, we imagine institutions such as Oxford or Harvard as metonyms for the “brilliant mind,” or perhaps envision a Nobel Laureate or Fields Medal winner. One component of this prestige is selectivity — from many, few are chosen. The same is true for scientific journals. While both journals and individuals project their prestige through reputation, journals have found ways to signal prestige through metrics such as impact factor, acceptance rate, and journal rankings; each suggesting the difficulty of publication and the likelihood that an individual’s work will receive institutional acclaim as a result.

At the dawn of the 19th century, approximately 100 scientific periodicals existed worldwide, and by its close, this number had risen to an estimated 10,000. Such growth marked a new era of independent scientific periodicals, distinct from traditional society publications. In such a competitive landscape, most of these publications clung to a tenuous existence, with prominent titles like The Reader (founded 1863) and Scientific Opinion (1864) struggling financially before ultimately folding. Even established and reputable periodicals, such as Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, which had enjoyed royal patronage since it was formally taken over by the Royal Society in 1752, rarely made money and struggled to publish without assistance.

When Norman Lockyer and Alexander Macmillan launched Nature on November 4th, 1869, they did so amidst a graveyard of failed scientific periodicals. That Nature survived while so many publications collapsed reflects not only scientific merit, but patronage, elite networks, speed of publication, and a talent for capturing an international audience.

From these advantages emerged not only a successful journal but also a system of prestige that continues to shape modern science. Prestige in this system is not simply a reflection of pure scientific merit, as one would hope, but a fiction that attempts to command attention in an era where the quantity of research far exceeds an individual’s capacity to assess it.

Today, this system faces serious scrutiny, with many questioning whether selective journals serve science beyond merely rationing merit. Understanding how Nature’s prestige was constructed, however, can help clarify which elements are deserved and which are entrenched.

{{signup}}

Founding Nature

Many of the features that would come to define Nature emerged in its earliest years. Survival was not inevitable, ultimately resting upon three contingent advantages: patronage that insulated it from commercial failure, elite networks that conferred early credibility, and a publication speed responsive to the increasingly competitive scientific environment.

Initially, what distinguished Nature from its failed contemporaries was the patronage of Alexander Macmillan, who, alongside his brother, had built Macmillan & Co. into one of Britain’s most successful publishers. Flush from a remarkably profitable decade built on fiction, theological texts, and educational works, Macmillan was eager to expand his empire and could afford to absorb the financial losses that would have buried other periodicals (which he did, for the thirty years before Nature began turning a profit).

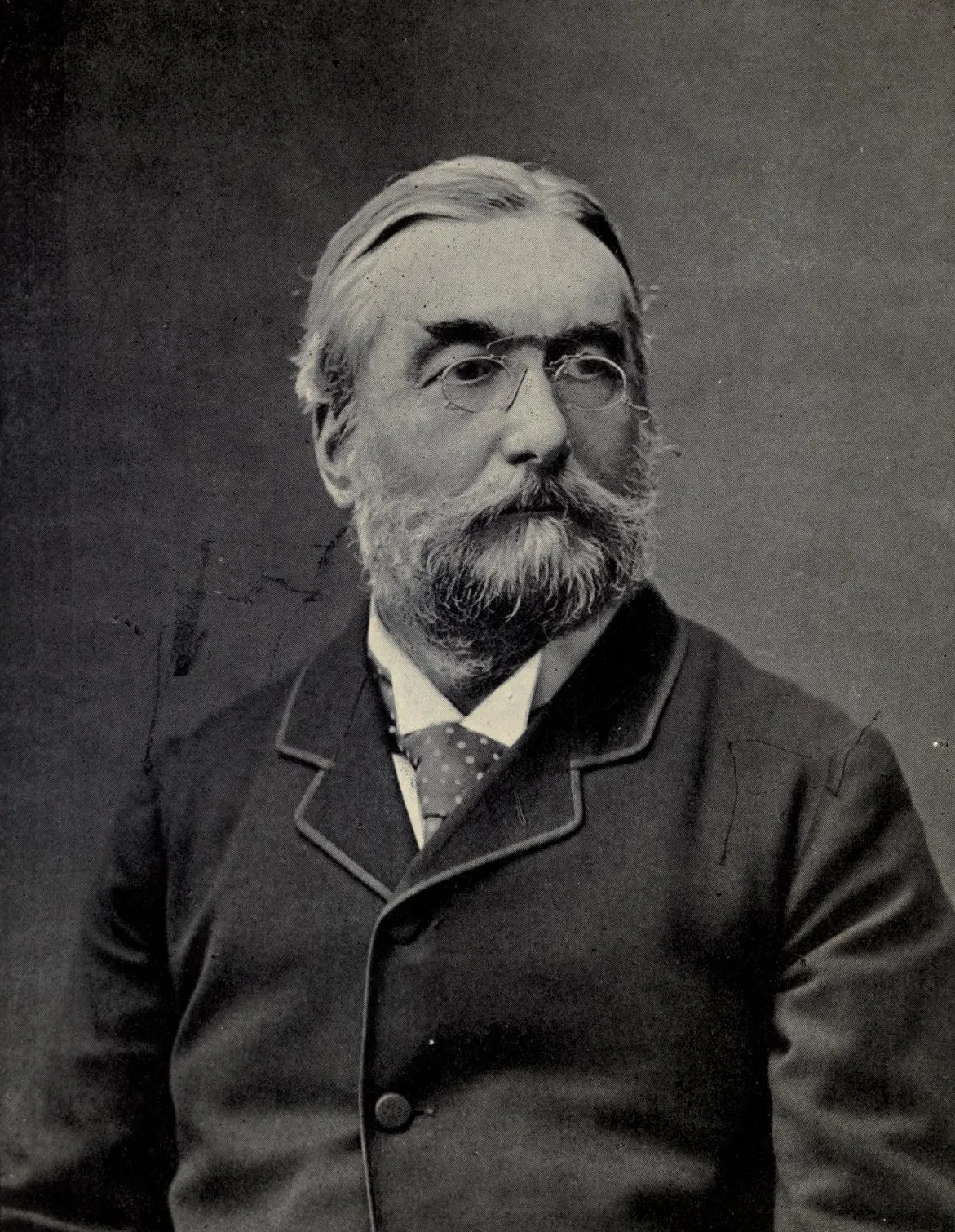

Macmillan already knew Lockyer. Indeed, Lockyer’s Elementary Lessons in Astronomy (1868) had sold well for Macmillan, who then employed him as his most important “consulting physician in regard to scientific books and schemes.” Lockyer was at the zenith of his early career, co-discovering helium with Pierre Jules Janssen in 18681 and elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1869.

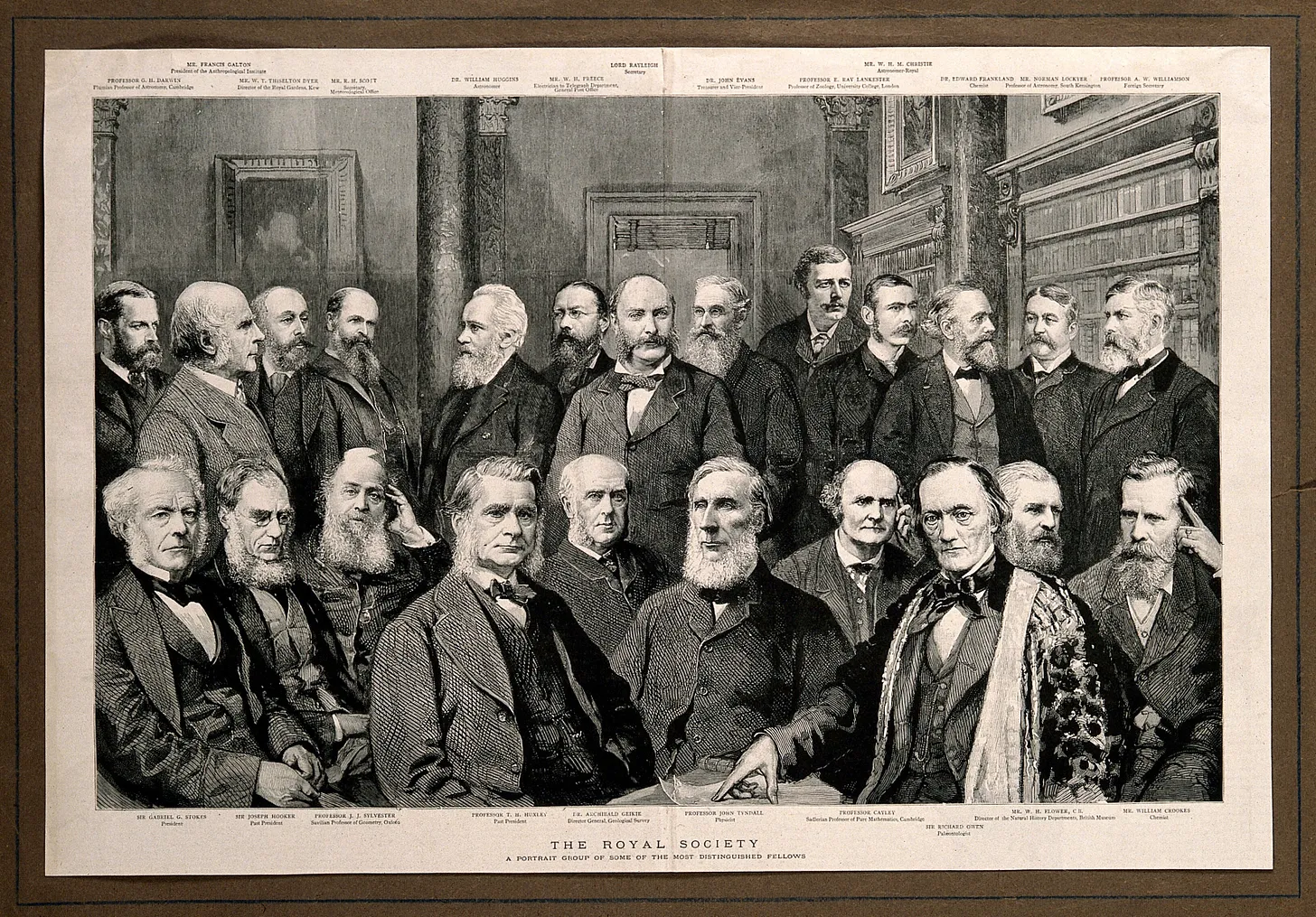

Had Lockyer’s reputation not been what it was, Nature would have perished. Patronage secured survival, but credibility required connection. Lockyer’s prior editorship of The Reader had linked him to influential scientific circles, most notably the English biologist Thomas Huxley and the X-Club. This informal dining society of nine prominent scientists, formed in 1864 and meeting monthly, exercised considerable influence over British scientific institutions and publications, promoting scientific naturalism and working to establish science as a professional, secular discipline independent of ecclesiastical authority.

Huxley, alarmed by scientific errors in popular books and frustrated by theological overtones he believed many journalists (particularly women) wove into their writing, concluded that only researchers themselves could properly educate the public. Through his enthusiastic support, Nature found an early contributor with an interest in scientific journalism unusual for a man of his scientific stature. Huxley, for his part, relished the attention, musing that when it came to journalism, he was “as spoiled as a maiden with many wooers.” Huxley also encouraged other prominent figures to contribute, even though they generally preferred to publish lengthy scientific essays in more established monthly periodicals.

While attracting prominent contributors was beneficial, the early editorial approach of Nature was unconventional. Lockyer envisioned the journal serving two audiences: educated laypeople seeking accessible science and professional researchers eager to learn about the latest advances.

Avoiding the abstract, passive voice of specialist journals, many popular articles in Nature were written in an accessible first-person, journalistic style. Observations from readers of a decidedly less technical nature were featured, including a report of a pigeon’s cunning method of procuring food by repeatedly startling a horse to shake grain from its nose-bag and an account of a goose raised by a Golden Eagle and taught “to eat flesh.”

Gradually, such whimsical observations yielded space to more technical book reviews and papers. Lockyer, who had hoped for favor from both the intellectually sophisticated layman and the scientific community, found that he mostly attracted the latter. Nature became a publication with short publication cycles and brief articles, with little elaboration or color.

Many scientists viewed these changes positively, regarding Nature as an efficient means to highlight a scientific idea. Capturing this sentiment, William Crookes, who would later become President of the Royal Society and one of the discoverers of Thallium, requested in an 1895 letter to Lockyer that his paper on helium’s spectrum appear in Nature even though it would already be published in his own Chemical News: “my circulation is not to the same class of researchers as that of ‘Nature,’ and having taken a great deal of trouble about it I want the results to get to the right people.”

Nature had cultivated this readership of active researchers through publication speed: its weekly schedule made it essential reading for scientists tracking developments in increasingly competitive fields. As to why such speed was possible, one likely factor was economic. Macmillan absorbed the financial losses that more frequent publication required, losses that would have crippled competitors, while society journals generally operated on quarterly schedules tied to meeting proceedings, creating inherent publication delays.

The strategic utility of this model became evident in how researchers employed the journal. One example was George Romanes, a seminal figure of comparative psychology and popularizer of “neo-Darwinism,” who presented his theory of “physiological selection” to the Linnean Society in May 1886 before publishing detailed abstracts across three consecutive August issues of Nature to establish priority.

The success of Nature’s approach was recognized internationally, with the first editor of Science declaring his desire that it may “in the United States, take the position which Nature so ably occupies in England, in presenting immediate information of scientific events.”

Speed of publication would have meant little, of course, without credibility. Although Nature initially drew legitimacy from its X-Club connections, this proved fragile. Lockyer’s commitment to editorial independence conflicted with the Club’s expectation that the journal would reliably advance its interests. Disputes followed, beginning in 1872 with the Hooker-Owen controversy, where Nature published Joseph Hooker’s defense against Richard Owen’s accusations of mismanaging Kew Gardens, and then gave Owen space to respond with his rebuttal. Hooker, a prominent X-Club member, regarded the platforming of his opponent as an act of disloyalty, while Lockyer argued that the journal could not be “the mere mouthpiece of a clique.”

Thoroughly annoyed with Lockyer and losing much of their initial enthusiasm, the X-Club’s contributions to Nature began to decline, further isolating the publication’s lay readership by depriving them of the popular articles the Club had regularly provided. Yet this development did not significantly undermine Nature’s credibility within the scientific community. The X-Club still faced opposition from many important scientists who continued to contribute to the journal, while the Club’s own influence was waning due to internal conflicts and its aging membership, leading to its disbanding in 1892.

More significantly, a new generation of scientists was beginning to assume leadership of the British scientific community, and this cohort would include some of Nature’s most important and prolific contributors of the late nineteenth century, such as eminent zoologist Ray Lankester, physicist Oliver Lodge (a giant in radio communication), and George Romanes, a protégé of Darwin.

Unlike their predecessors, whose preferred medium for scientific debate tended to be long-form periodicals, this new generation generally preferred Nature, often redirecting debate to its pages. Debates were structured, combative exchanges, featuring formal turn-taking and explicit rebuttals.

One noteworthy debate centered on Weismann’s theory of panmixia, which proposed that when an organ no longer conferred an evolutionary advantage, that organ would no longer be the subject of natural selection, leading it to diminish in size or vanish entirely. George Romanes endorsed this view in Nature, prompting Lankester to challenge him directly, arguing that a “useless” organ would be equally inclined to grow or diminish, and that panmixia could not account for reduction unless smaller size itself conferred an advantage. The exchange extended over eight weeks in Nature’s pages, with Romanes refusing to concede and instead insisting that Lankester fundamentally misunderstood his position.

By the close of the century, such exchanges had become familiar features of Nature’s pages. The lay reader had largely left Nature, which now served primarily as a medium for the scientific community. Prominent figures continued to contribute at rates often exceeding the prior generation and demonstrated an increased willingness to position Nature at the center of British scientific discourse.

Entering the 20th Century

For all its growing influence, Nature wasn’t yet particularly prestigious. It lacked the rigor of journals like Annalen der Physik or the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, finding survival through patronage and speed.2 At this time, Richard Gregory, an administrator rather than a practicing scientist, was hired as Nature’s editor-in-chief in 1919 — a smart choice given that many of Nature’s challenges were operational rather than scientific.

Sensible of his own limitations, Gregory had positioned himself not as a “man of science,” but as a “spokesman of science.” As a spokesman, Gregory was oriented more towards advocacy and would extend such efforts beyond Britain, positioning Nature as an international venue protecting scientific freedoms.

Starting in 1933, for example, Nature began criticizing the Nazi regime for their expulsions of Jewish scientists. The Nazi regime banned the journal from German libraries in 1937. Gregory later defended this position forcefully, arguing that only “a German political official” would expect scientists to remain silent while respected colleagues were expelled “as the result of bitter racial prejudice.”

By taking such a principled stance, Gregory established Nature as a venue where scientific merit transcended national interests, drawing cutting-edge researchers from around the world and elevating the journal’s international profile. Perhaps their most significant international contributor was the physicist Ernest Rutherford, a New Zealand-born physicist and Nobel laureate whose work on radioactivity was reshaping atomic theory. Rutherford benefited greatly from Nature’s rapid publication schedule to announce discoveries from his laboratories in Montreal and later Cambridge. His explicit use of Nature to “keep in the race,” particularly after being “scooped” by the Curies in 1899, captured a shift where speed of communication was becoming essential to participate in cutting-edge research.

This pattern made Nature unusual among prominent journals: domestic contributions steadily declined over time. By 1933, half of Nature’s letters came from outside Britain. By contrast, Science remained predominantly American even later in the century (by 1980, only 15 percent of its experimental content came from abroad). In making Nature international when most other journals remained domestic, Gregory had established what would become a keystone of Nature’s future prestige.

Yet progress was fragile, with the international vision waning under Gregory’s successors, A.J.V Gale and Lionel “Jack” Brimble. Viewing their role as publishing “as many credible scientific papers — particularly ones from respectable British laboratories — as possible,” editorial selections became more domestic as English was displacing German and French as science’s lingua franca.

That said, their passive editorial approach meant they largely accommodated, rather than restricted, international submissions. By 1965, nearly 60 percent3 of all articles and letters originated from abroad. This shift was largely contributor-driven, as scientists worldwide continued to see Nature’s utility for gaining visibility and establishing priority findings.

Adopting such a hands-off approach had consequences for editorial quality, however. Nature developed a reputation for printing almost anything that wasn’t demonstrably wrong, with editorial decisions often relying disproportionately on institutional prestige as a filter. One notable editorial misjudgment was the geophysicist Lawrence Morley’s seafloor spreading hypothesis, submitted from Canada in February 1963, which was dismissed by Nature’s referee as mere “talk at cocktail parties.” Seven months later, Vine and Matthew’s virtually identical hypothesis, bearing Cambridge credentials, sailed through to publication in what became known, with belated justice, as the Vine-Matthews-Morley hypothesis.

Still not considered a particularly prestigious journal by the mid-1960s, Nature suffered from mediocre output, erratic refereeing, and publication delays that exceeded 14 months, eroding the speed that had once been one of its strongest competitive advantages.4 As geologist Drummond Matthews (of Vine-Matthews-Morley fame) would later recall, Nature “dropped into a sort of vacuum … American labs wouldn’t hear anything of it — thought it was all nonsense.”

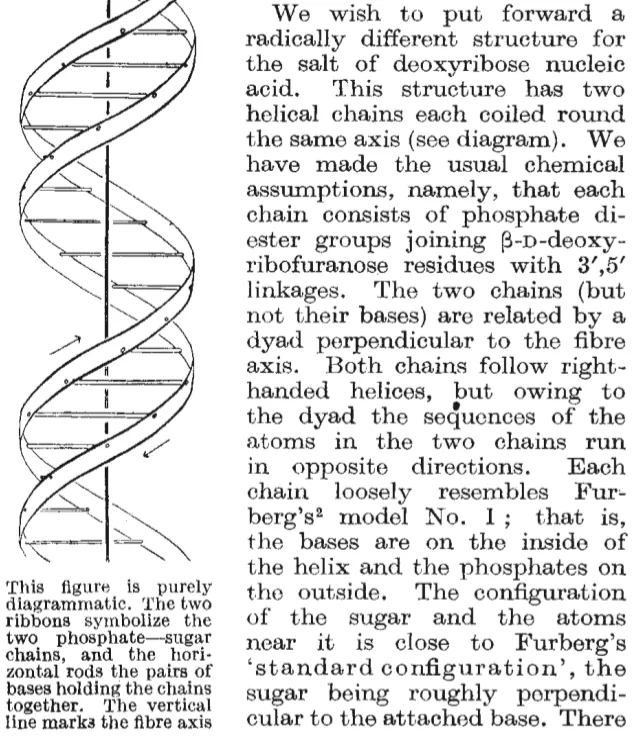

Yet, Nature’s position within Britain’s scientific establishment still attracted significant breakthroughs, particularly in biological sciences, where the editors had actual expertise. Perhaps most famously, Watson and Crick’s 1953 DNA structure paper was accepted within three weeks, without external peer review, after Physics Nobel Laureate Lawrence Bragg sent a “strong covering letter” to the editors, whom he knew personally.5

With a reputation resting less on systematic editorial excellence and more on adjacency to transformative figures, Nature was — confusingly — both a second-tier outlet and a site for breakthroughs that reshaped entire fields.

The Turning Point

Gifted this unhappy inheritance in 1966, editor John Maddox set about transforming Nature from survivor to standard-bearer, confronting a publication backlog of six months or more — nearly 2,000 manuscripts — left behind by Brimble and Gale’s passive editorial approach. He would first restore the submission processing speed that had deteriorated under his predecessors, pursuing a more assertive editorial strategy, and laying the foundation for the selectivity that would come to define Nature’s modern identity.

To speed up article processing, Maddox imposed discipline: instituting daily editorial meetings and introducing a streamlined index-card tracking system6 that sped up publication. By December 1966, he was even printing submission dates to signal the journal’s restored speed.7

Perhaps the greatest departure from previous editorships was Maddox’s view that Nature was engaged in direct competition with other journals. Maddox pursued an editorial strategy that actively courted laboratory submissions, sometimes convincing authors to withdraw their manuscripts from rival periodicals.8 By courting higher-quality submissions and publishing them quickly, Maddox restored much of Nature’s reputation. This success did, however, create an issue: rising submissions overwhelmed the journal.

By default, this made Nature more exclusive. Maddox, for his part, didn’t necessarily want this; he was more interested in breaking news and saw gatekeeping more as a means to that end. So he attempted to implement a three-journal solution, splitting the original journal into Nature, Nature New Biology, and Nature Physical Science in 1971. The plan reflected Maddox’s journalistic instincts: print more papers, publish more frequently, move faster, perhaps even toward a “daily Nature” that functioned like a scientific newspaper.

Unfortunately for Maddox, this backfired. Authors in the satellite journals felt “demoted to the second division,” while British researchers appeared disproportionately in the flagship (over 50 percent) compared to the satellites (~33 percent), reinforcing perceptions of Nature as a “very British establishment journal.” When Nature recorded a financial loss at the end of 1972, Maddox was replaced.9

In 1973, Nature’s new editor, David Davies, scrapped the three-journal plan, returning to a single title while retaining Maddox's operational improvements. With submissions continuing to grow but channeled through one outlet rather than three, Nature rejection rates continued to rise. Authors sought out Nature not only for visibility but for the symbolic capital it conferred. For the aspiring scientist navigating an environment where funding had slowed and, in many fields, shrunk, publication in Nature represented a form of career insurance.

However, exclusivity was an asset only if it was perceived as legitimate. Davies set out to reform the editorial process, moving it from the insular circles that had characterized earlier periods.

Within the first year of his editorship, Davies made peer review a requirement. Nature was late to this practice — American journals had been experimenting with peer review since the 1940s, and institutionalizing it since the 1960s — but the timing proved strategically important: U.S. academic departments increasingly demanded peer-reviewed publications for tenure decisions.

Ultimately, peer review didn’t transform Nature’s standing so much as protect it, converting exclusivity that might have seemed arbitrary into gatekeeping that appeared meritocratic.

Together, Davies and Maddox had directed a significant transformation. By the late 1970s, they had created the essential architecture of modern Nature — a highly selective, internationally oriented, generalist publication. This architecture allowed Nature publications to function as Schelling points,10 coordinating attention and providing shared references that researchers across disciplines could build on without extensive explanation. Nature’s prestige, in other words, derived less from gatekeeping quality than from solving a coordination problem.

And by solving that problem, Nature became valuable as career insurance. Publication in Nature provided a universally recognized signal for hiring committees, grant reviewers, and colleagues. It also had scientific value, because breakthroughs often arise when researchers apply principles from their own discipline to another. A paper’s inclusion alongside others of unrelated inquiry thereby indicated that a scientist’s work wasn’t only impactful in their own field but contributed to science on the whole.

Davies, who believed that staying in the same role too long led to personal stagnation, left Nature in 1980. To the surprise of many, including Davies, he was to be replaced by a returning Maddox, whose reappointment was facilitated by management changes at Macmillan, particularly the declining influence of one of its publishing executives, Jenny Hughes, who had orchestrated his prior exit.

Upon returning, Maddox set out to establish Nature as the definitive publication for the international scientific community. By 1980, four-fifths of articles and letters already originated from outside Britain. Nature extended this reach by opening offices in Tokyo, Paris, Munich, and Hong Kong. International expansion was accompanied by increased selectivity. By the late 1980s, Nature’s acceptance rate had fallen to just 12.5 percent (down from 35 percent in 1974), making publication more highly coveted; for comparison, editor Daniel Koshland Jr. reported Science’s acceptance rate at approximately 20 percent in 1985.

Throughout both editorships, Maddox had maintained a conviction that a scientific journal “should have an opinion on the state of science,” rather than serving as a passive conduit. During his first tenure, Maddox had personally taken over writing editorials, often at the last minute, to keep them current and provocative, and restructured the journal to place news and opinion prominently at the front. His second tenure would see a more direct approach, albeit sometimes controversially, such as when he personally investigated claims about homeopathy in 1988, drawing criticism for creating a “circus” atmosphere, and again when he deployed editorial skepticism against cold fusion claims the following year.

Despite such blips, by 1995, Nature had largely solidified its position through its core strengths. Its selectivity made publication valued across the global scientific community. Its international reach connected researchers. Finally, its approval had become one of science’s most valued forms of validation.

Nature in the New Millennium

Upon assuming the editorship in 1995, Philip Campbell — a physicist who had spent the previous decade in science publishing, including as founding editor of the magazine Physics World — was tasked with preserving the legacy of Davies and Maddox as the journal transitioned from print to pixel. Through editorial independence, digital presence, and selective competitive engagement, Nature would continue to strengthen its institutional position.

Institutional security, however, often rested on foundations beyond Campbell’s direct editorial control. During Campbell’s editorship, Nature’s portfolio expanded significantly: though sub-journals had resumed under Maddox with Nature Genetics in 1992, Campbell’s tenure would see them increase in number from 3 in 1995, to 30 by 2018, with many more partner journals.11

Campbell and other editors proposed or were consulted about new journal content; in the 2010s, he recalls supporting the initiation and early development of multidisciplinary thematic journals such as Nature Climate Change and Nature Sustainability. This devolved authority operated across multiple levels: issue-by-issue editorial decisions remained independent from corporate strategy, the journal and magazine maintained independence from one another, and individual Nature-branded journals operated independently from the flagship.12

Another significant development during Campbell’s tenure was the digitization of Nature content. Just as Davies had protected Nature’s standing through peer review — not by implementing it brilliantly, but by ensuring its absence couldn’t be used against the journal — digitization served a similar defensive function. Even though nature.com launched inauspiciously in 1995, with limited content, technical issues, and no full papers, its existence mattered more than its execution. This imperfect step, taken to be seen as modern and avoid anachronism, would prove foundational as scientific communication moved overwhelmingly online.

Campbell’s control was primarily editorial; for example, he sought to boost Nature’s attention to research themes he felt were undersupported, expanding coverage of foundational themes like methodology and scientific integrity, as well as specific subject matter such as marine science and mental health. Campbell also initiated greater engagement with the social sciences across Nature’s magazine and journal content, which underpinned the subsequent expansion of multidisciplinary research in Nature and its thematic journals beyond the natural sciences.

Editorial independence remained important, even when at odds with the publisher’s interests. One example of this independence was the Human Genome Project, an international project to sequence, map, and identify all human DNA. In 2000, Craig Venter’s Celera Genomics and the public Human Genome Project were completing their sequences, with Science pursuing both manuscripts. Venter insisted that some data remain behind a paywall (a position not considered heretical at the time). Campbell, however, refused these terms, judging it more important that data published in Nature remain publicly accessible, even at the risk of losing both sequences to Science. Venter did indeed go to Science, though Nature was able to publish the public project.

Similarly, when DORA (the Declaration on Research Assessment; an initiative advocating for the evaluation of research on its own merits rather than relying on journal metrics) launched in 2012, Nature abandoned a marketing campaign that had highlighted impact factor as a way to boost subscriptions. Campbell had been a longstanding critic of impact factor, though Nature had continued employing the metric in its marketing. Their public endorsement of DORA, however, cast this reversal as a matter of principle, giving Nature reputational capital for championing fairer evaluation practices. While this action carried some cost in absolute terms (abandoning a successful marketing lever isn’t nothing) Nature’s market position made this cost bearable, whereas it would have been prohibitive for a less established journal.

Perhaps most unusual about Campbell was that he approached rivalry selectively. He was seemingly indifferent to ordinary competition, but would pursue landmark contests intensely. “I can honestly say that we spent little time looking at what other journals were doing,” he would later muse.13 But when the symbolic value justified a more intensive pursuit, such as the Genome Project, Nature would compete aggressively. Otherwise, Campbell operated with a “room for both” philosophy regarding Science, seeing each journal as serving its own constituency. This selective engagement reveals that Nature’s strength during this period came not from controlling everything, but from knowing what mattered for preserving its position.

Modern Nature

When Magdalena Skipper, the current editor-in-chief, succeeded Campbell in 2018, she commanded a journal whose reach and influence surpassed anything her predecessors had inherited. Yet the surrounding scientific ecosystem was also far less stable. Preprints had matured through platforms like bioRxiv and arXiv, the open science movement was gathering momentum with initiatives like Plan S14 and platforms such as PLOS ONE,15 and conventional scientific institutions faced mounting scrutiny.

Where Campbell had practiced selective indifference to competition, Skipper brought a different sensibility, actively monitoring rivals. Attentiveness to competition extended beyond traditional academic journals to include outlets such as The Guardian and Financial Times, all competing for mainstream public attention on scientific developments, particularly during the pandemic. Although Nature held scientific authority, these mainstream outlets commanded greater public reach.

While Nature cannot beat these publishing giants on reach, Skipper’s ambition to foster “true multidisciplinarity” does extend its breadth. Throughout history, she observes, Nature has been “multidisciplinary primarily within the natural sciences.” Under Skipper, the journal has expanded into physical sciences, clinical research, social sciences, and engineering. Skipper’s guiding idea is that today’s most pressing questions demand collaboration across fields: “innovation often comes with an element of social sciences,” she says.16

Widening the lens, however, doesn’t mean capturing everything. Skipper advocates for an “ecosystem with different publishing approaches: inclusive and selective.” Not everything requires Nature-level selectivity; there is value in venues for replication, negative results, and less conventionally interesting datasets. Publishing, she contends, is inseparable from research itself: “not thinking about publication when conducting research is a conceptual error,” as research without dissemination has limited value.

For the critic of scientific publishing, however, it’s the journal itself, no matter how inclusive or reformed, that is the problem. In June 2025, Astera Institute, a nonprofit research organization, announced it would no longer fund traditional journal publications. For Astera, the journal system has flaws so deeply entrenched that they resist reform: publications become final stamps of approval with mistakes rarely corrected, artificial scarcity fuels competition over collaboration, and articles don’t adapt as new evidence emerges, allowing flawed studies to mislead fields for decades.17

While quite the indictment, there is merit to many of these complaints. As such, there are reforms that journals can implement that attempt to redress them. One especially illustrative example (although there are others) is retraction. Skipper considers it in Nature’s interest to “clean up [its] own pages.” She views retractions as visible evidence of vigilance rather than hidden embarrassment. Indeed, Springer Nature18 retracted 2,923 papers in 2024, with 61.5 percent addressing historical papers published before January 2023 as part of what the company describes as its commitment to “cleaning up the academic record.”

That said, these retraction efforts are not as thorough as they sound. This is because the complexity of removal processes and procedural requirements can override editorial judgment and stifle effectiveness. For example, in December 2016, independent researchers published an investigation uncovering nearly 300 fraudulent papers by two Japanese physicians, Yoshihiro Sato and Jun Iwamoto, across 78 journals. Among the publishers implicated was Springer Nature, which (as of 2024) had only retracted 13 of the 45 Sato-Iwamoto papers it had published.

Arguably more troubling was that at the Journal of Bone and Mineral Metabolism (a Springer Nature journal), only one of eleven papers was retracted, despite the editors recommending withdrawal, because the institutional investigation remained incomplete. Although the intention to reform may be sincere, procedural dependencies can override editorial judgment.19

Unlike her predecessors, who established Nature as the central hub for international science, Skipper must now defend that position against emerging alternatives in a maturing ecosystem of preprints, open access mandates, and funder defection. What her predecessors could largely take for granted — that a selective, central venue served science well — is itself contested.

Ultimately, the question isn’t so much whether Nature deserves its prestige (history shows that much of its success has been circumstantial and opportunistic rather than meritorious) but whether the coordination function it now serves is sufficiently valuable to the scientific ecosystem.

After all, in building its prestige, Nature became a vehicle for features that make scientific ecosystems function: international collaboration, multidisciplinarity, rigor and evaluation, and reach. Prestige may connote selectivity, but it speaks more to the broader question of what science is valuable and, as history demonstrates, that question was never answered by merit alone. Elite networks and well-endowed institutions may have shaped Nature’s ascension, but we should not mistake the system that emerged for one that reliably surfaces the best work.

Prestige journals became a default filter, but even that may be fragmenting. As submissions outpace what peer review can absorb, prestige risks becoming a marker of scarcity rather than quality, while scientific discourse migrates to faster venues. Yet coordination without quality control is insufficient. Not all science is equally valuable, and not all scientists have the same amount of integrity. In the era of paper mills, AI slop, and epistemic pollution, whatever system comes next — whether prestige journals or something else entirely — must contend with how to navigate this noise. We have seen one way to do this and understand how we arrived there. We may well need another.

{{signup}}

{{divider}}

Robert Reason is a Parliamentary Researcher. His prior academic work includes research on economics, metascience, and political misinformation.

Thanks to Melinda Baldwin for her foundational book, Making Nature: The History of a Scientific Journal, and her time in discussion, and to Philip Campbell and Magdalena Skipper for their generous and insightful interviews. These interviews heavily inform the sections about their editorships. Header image by Ella Watkins-Dulaney.

Cite: Reason, R. “How Nature Became a ‘Prestige’ Journal.” Asimov Press (2026). https://doi.org/10.62211/27hq-98kj

This article was originally published on 4 January 2025.

{{divider}}

Footnotes

- The two men independently arrived at the discovery some 5,000 miles apart, but submitted their papers to the French Academy of Sciences on the very same day.

- Quality control during this period generally relied on editorial judgment and consultation with trusted advisers rather than systematic peer review, with prestige reflecting the quality of these networks. Annalen der Physik was perhaps most famous for publishing Einstein’s annus mirabilis papers in 1905: including work on the photoelectric effect, brownian motion, special relativity, and the principle of mass-energy equivalence.

- Wartime disruptions had left Nature with a predominantly British author base in the 1940s, but by 1950 around 40 percent of "Letters to the Editor" came from outside Britain, although over 70 percent of longer research articles remained British; this continued to rise throughout the Gale and Brimble editorship.

- One 1972 analysis found that Nature ranked 114th in impact factor among journals, based on citations in 1969 to articles published in 1967-1968, with an impact factor of 2.3.

- Crick published 29 papers in Nature over his lifetime, including his landmark 1961 paper with Sydney Brenner and colleagues on the genetic code and triplet codons.

- Though the idea and execution of this was largely driven by Mary Sheehan, an assistant to Maddox.

- This was, however, relatively short-lived (though much improved compared to Gale and Brimble) as operational efficiency declined during Maddox’s editorship, often because he was overly involved in the process. Davies also added time to this with the addition of compulsory peer-review.

- Melinda Baldwin, based on an interview with Walter Gratzer (senior Nature editor under Maddox) and cited in Making Nature. Specific manuscript examples were not documented.

- This failed financially, as the printing of three journals was expensive. Authors who submitted to Nature also expected their work to appear in the main journal, rather than diverted to sub-journals.

- A Schelling point is a focal point for coordination where participants independently converge on the same solution because it seems like the natural or obvious choice, without requiring explicit agreement.

- This expansion was likely enabled by digital publishing: from 2010, Nature launched some specialized journals as digital-only ventures, reducing the costs that had previously limited the number of viable titles.

- Whereas the sub-journals of the 1970s were effectively satellites of Nature, by the 1990s the new titles had their own editors and identities, operating as distinct journals in their own right.

- Quote from an in-person interview with Philip Campbell.

- Plan S is an initiative by cOAlition S, a group of international research funders, requiring that all scholarly publications that they fund be published with immediate open access beginning in 2021.

- Public Library of Science (PLOS) ONE is a multidisciplinary, peer-reviewed, open access journal that evaluates research based on scientific rigor and methodology rather than perceived significance or novelty.

- Quotes in this section are from in-person interview with Magdalena Skipper.

- One example is the 5-HTTLPR gene being incorrectly labeled a cause of depression. A second is research on Aβ*56 (amyloid beta star 56) being fabricated to support the amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease (which was published in Nature).

- Springer Nature, formed in 2015 from the merger of Springer and Macmillan’s Nature Publishing Group, is the academic publisher that owns Nature and its family of specialist journals.

- Some relatively low-hanging reforms could include: retraction notices that specify errors precisely rather than vaguely; assignment of responsibility where feasible to protect innocent co-authors from blanket stigma; publication of peer reviews alongside papers (something Skipper has introduced to Nature); and distinction between fraud and honest error in retraction language to encourage self-correction.

Always free. No ads. Richly storied.

Always free. No ads. Richly storied.

Always free. No ads. Richly storied.