Mystery of the Head Activator

Most of the people in this story have already died, but there are still some who remember a finding that captivated the developmental biology field decades ago. The story concerns a molecule, known as the “head activator,” which was believed at that time to be a short neuropeptide necessary for head regeneration in the freshwater cnidarian hydra.

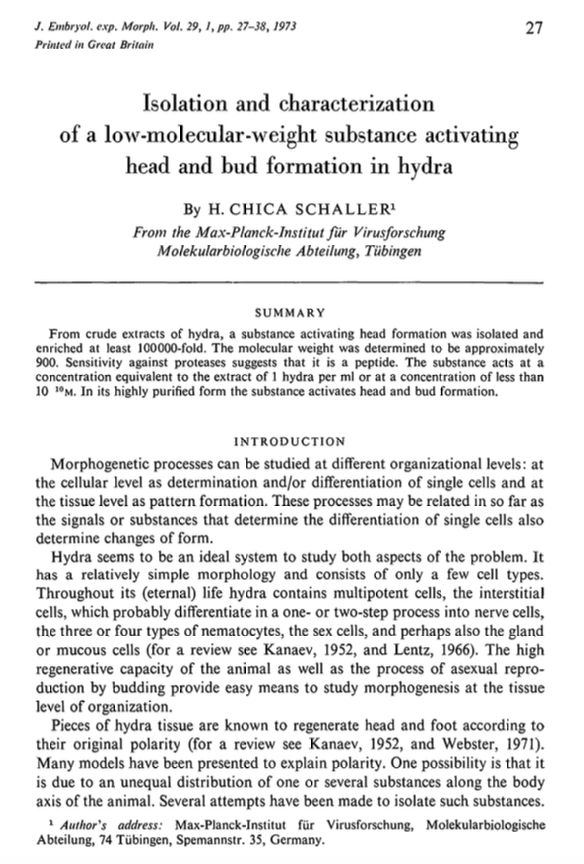

In 1973, a German graduate student named H. “Chica” Schaller published a paper under the prolix title: “Isolation and characterization of a low-molecular-weight substance activating head and bud formation in hydra.” The work was conducted in the Alfred Gierer lab at the Max-Planck-Institute for Virus Research in Tübingen, Germany. The lab had been working to understand morphogenesis (the process by which an organism develops) in Hydra attenuata. In the course of this work, they uncovered a substance that they claimed was responsible for initiating head formation in hydra.

Chica’s paper emerged as the fields of developmental biology and molecular biology were intersecting. In 1924, Hans Spemann and Hilde Mangold demonstrated the concept of an “organizer”— a cluster of cells within the newt embryo that could induce or guide the development of surrounding tissue when inserted in another species of newt. In the elapsing decades, the field had observed similar organizational activity across species, but the molecular underpinnings for these phenomena were unknown. Chica’s 1973 paper drew on these findings to propose a similar mechanism in hydra, putting her name on the developmental biology map.

Later, she and her colleague Hans Bodemüller would sequence the substance — the first morphogen ever sequenced, actually — and make it available to any interested researcher. The head activator became synonymous with Chica’s name. Over the years that followed, both she and her colleagues published a string of papers about it, as well as studies on inhibitors in hydra, and Chica was asked to present at conferences in both Europe and the U.S.

The problem was that her findings were seemingly impossible to replicate. Both her early colleagues and the people in the larger Hydra field eventually abandoned them: Stefan Berking was unable to repeat her work; Charles David watched as new explanations for hydra morphogenesis arose; and Robert Steele decided her claims weren’t worth wasting funding dollars on.

Today, while the Hydra remains a useful model for the study of nerve nets, aging, and regenerative medicine, new explanations have emerged to explain morphogenesis in hydra. The mystery of Chica’s “head activator” has never been solved. The history of how it was discovered and eventually rejected illustrates how science progressed over her lifetime, moving from embryology to molecular biology to genetics.

But the real reason I spent months reading and translating books and calling around to locate interview subjects was to understand how this mystery affected the people involved; to learn why the one person who openly challenged Chica and the head activator, a German biologist named Werner Müller, bore the scars of that battle to his grave.

{{signup}}

Beginnings

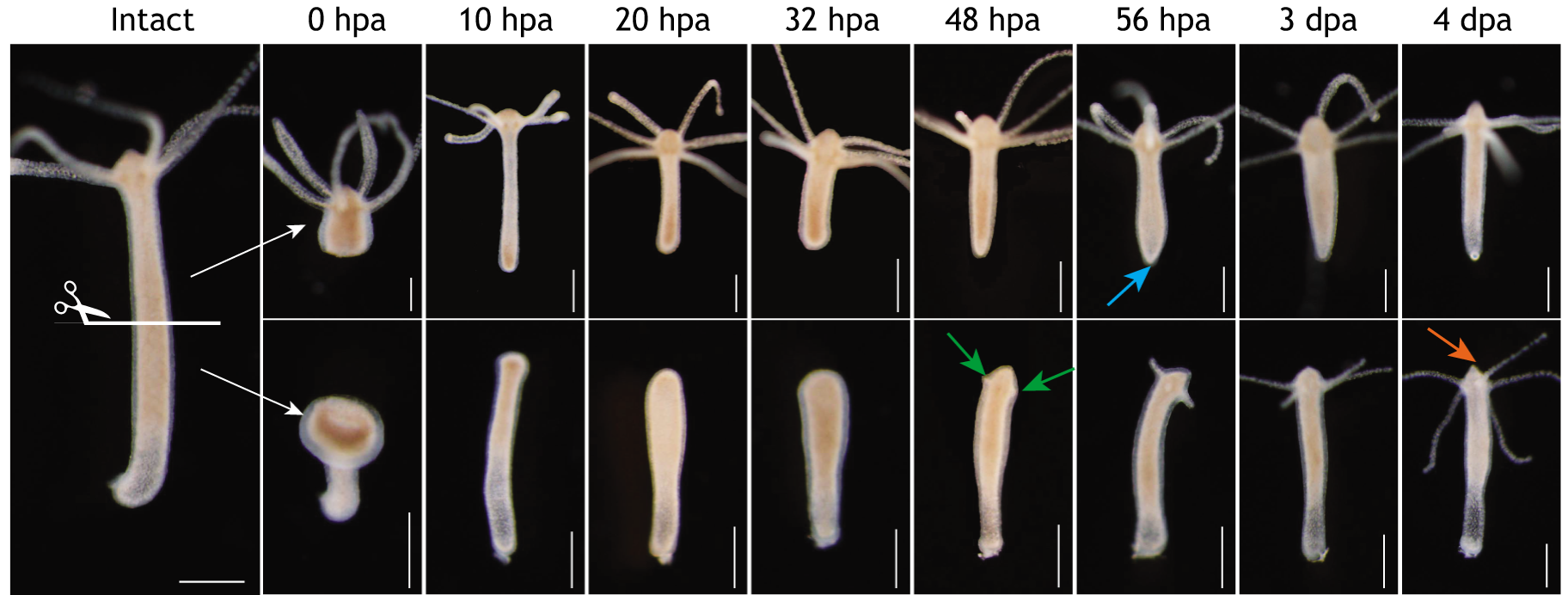

Hydra have a thin body column, generally shy of an inch, with a disk-like foot at one end and a mouth surrounded by tentacles at the other. The tentacles have stinging cells, and the animal eats by grabbing, paralyzing, and ingesting its prey, often small crustaceans. These cnidarians travel by somersaulting, head-over-foot, and they mostly reproduce by asexual budding. But because they possess a high proportion of stem cells, their bodies constantly renew and large portions can regenerate. For this reason, they are sometimes referred to as immortal.

The hydra is thought to have first been identified by Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, who observed it with his microscope. The naturalist Abraham Trembley, however, made it famous. Trembley came across the animal in 1739, a cylindrical thing attached to the stem of an aquatic plant he pulled from a ditch. He put the plant in a jar of water and watched the polyp reach upward with its thin arms. When he shook the jar, the creature contracted sharply, as if startled.

At first, Trembley thought the hydra was a plant, but when he cleaved it in two, severing the “foot” from the “head,” and witnessed both halves producing fully formed animals, something prickled in his brain. The more he observed “the two parts in which the reproduction” took place, he wrote, “the more their activity called to mind the image of an animal.”

Trembley set about examining the hydra in nearly every way possible: slicing it in half, attempting to turn one inside out, and removing its tentacles, chronicling these experiments exhaustively in his Mémoires.

Chica encountered the animal more than 250 years later. Born in 1937 in Alzney, Germany, her birth name was Hildegard Kornmayer. Her father died in World War II, and Chica sometimes thought of herself as a half-orphan. Her mother married again and ran the textiles business in her new husband’s successful department store.

Chica’s grades in high school were middling. But she had artistic leanings, writing poems and taking photographs, and she cultivated an independent streak — sometimes wearing tight, three-quarter-length pants, for instance, which was rare for women at the time.

After graduation, Chica attended the Heidelberg Dolmetscher-Institut, a language school, where she studied Spanish and English. She traveled to Spain in the summer of 1958 with a fellow linguist named AnnMarie, a tall, striking red-head. Chica was somewhat deferential to AnnMarie and gave her the nickname “Mammi.” In return, AnnMarie gave Hildegard the nickname “Chica,” a name she carried into her scientific life.

While playing tennis in Spain, AnneMarie met a German chemistry student from Heidelberg named Klaus, who sometimes brought along his friend Heinz Schaller, also a chemistry doctoral student. After they returned to Heidelberg, they stayed in touch. Chica and Schaller fell in love and married about two years later, before going to the University of Wisconsin at Madison for Schaller’s post-doctoral work.

Chica wasn’t happy abroad. She didn’t like Madison’s climate or people and was bored with the translating and secretarial work she was able to find. While she enjoyed the exploratory trips she and Schaller took through the country and Canada, she was happy to return to Germany in January 1963 when Schaller took a research associate position at the Max Planck Institute for Virus Research in Tübingen.

Chica, then 26, decided she needed more education and enrolled in a biology undergrad course with a focus on genetics and biochemistry. She graduated in five semesters and went directly into a PhD program in the winter of 1966-67, joining her husband at Max Planck, where she became Alfred Gierer’s graduate student.

Gierer had already been nominated for the Nobel Prize in Chemistry twice by this time, but he had become fascinated by the generation of spatial patterns — how tissues and cells become arranged — in developmental biology. His lab wasn’t quite sure how to study this, however, until an assistant professor in the zoology department, named Werner Müller, suggested they use the Hydra.

By the late 1960s, Gierer, the American postdocs Hans Bode and Charles David, and the German graduate students Stefan Berking, Ekkehard Trenkner, and Chica Schaller, were investigating the Hydra in earnest. They were joined by physicist Hans Meindhart, who wanted to explore biological questions via computer modeling. Gierer suggested they develop a theory for how hydra formed.

In 1972, the lab showed that the polarity of the morphogenesis in hydra came not from cellular orientation — where the cells were located in the animal — but from some other guiding principle. David recounted how the group could all but decimate a hydra, pushing the animal through a fine mesh, and from this “completely random mass of cells — let’s say 100,000 cells,” two polyps would form. “It takes four or five days to have this happen,” David told me, “but you’re creating order out of complete chaos.”

Later that year, Gierer and Meinhardt published the fundamental paper on this idea, entitled “A theory of biological pattern formation.” It established what would be called the Gierer-Meinhardt model, which explained, among other things, the way organized tissue arose from a mass of cells. This model, which built off earlier work by Alan Turing, showed that spatial order can emerge through interacting “morphogens”: an activator that promotes both its own production and that of an inhibitor, which diffuses more widely and suppresses the activator. This interplay of short-range activation and long-range inhibition, the paper asserted, could spontaneously generate organization, even without preexisting structure.

“For the first time,” David said, the paper “provided a very clear mechanism” for how activating and inhibiting substances along a gradient in the body of hydra could cause regeneration.

But no one knew what substances accounted for this, and Gierer asked Chica, his graduate student, to investigate. Chica began by reading the literature, including Lesh and Burnett, and Thomas L. Lentz, who published The Cell Biology of Hydra. She also read work by Müller, who had been searching for a substance that could cause regeneration in the cnidarian Hydractinia, and had made a similar attempt to “isolate and accumulate the ‘polarizing inducer’” in hydra. These researchers had all presented evidence that an unknown substance “is present in crude extracts of hydra that may determine head formation,” as Chica wrote in her 1973 thesis.

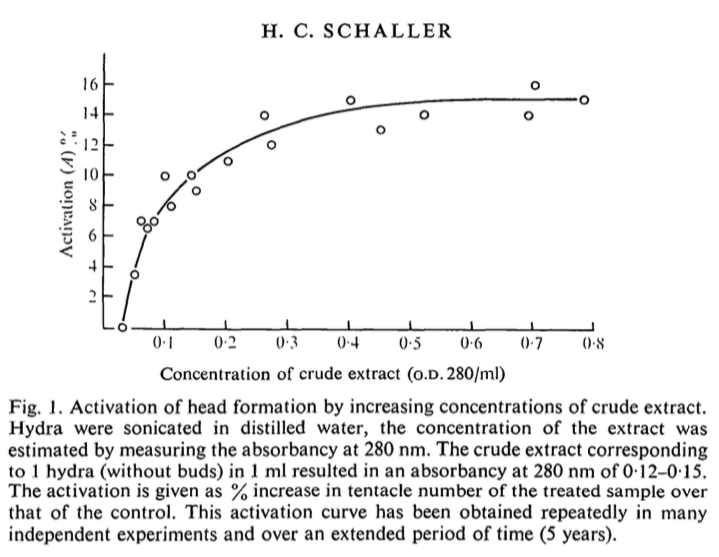

After years of work, Chica claimed to have found the “head activator” molecule; one of the four ingredients responsible for Hydra’s regenerative abilities. She had taken 30,000 hydra and used ultrasound to break open their cells, creating a crude extract that she spun down in a centrifuge. From this, she was able to isolate and enrich a substance of a low molecular weight that was susceptible to degradation by enzymes, suggesting it was likely a peptide.

Next, she set about testing the activity of the substance. She began with hydra that had been starved for 24 hours and showed no signs of growing a new head. Then she cut away the top of the animal, including its mouth and tentacles, and incubated the body stem for six hours in either regular hydra growth medium, or the same liquid with her isolated “head activator” substance added in. After those six hours, both groups of hydra were placed in regular growth medium and, after 48 hours, Chica counted and compared new tentacle growth between the two groups. The results showed, she wrote, that “in its purified form the substance not only stimulates the number of tentacles in regenerating animals and the rate of head regeneration, but also the number of buds and the rate of bud formation.”

Taken at face value, this experiment seemed to suggest that Chica had isolated one of the molecules behind head growth in hydra. The theory of morphogenesis had its first morphogen.

A Big Splash

Chica’s paper vaulted her to the top of the developmental biology world. She was asked to speak at conferences, both locally and in the United States. But the Gierer lab was young; its members needed to advance in their careers, and it split up around 1974. Bode eventually would move to a professorship at UC-Irvine. Berking continued studying morphogenesis in the Gierer lab, Trenkner moved to a postdoc in New York City, and David also went to New York, to Albert Einstein Medical School as an assistant professor.

Tension between Chica and Müller had already surfaced in Tübingen. Chica was “quite smart,” David told me, but she could have “a very loose tongue.” And she “took a dislike to Werner Müller, because he was absolutely the opposite. He was a staid, old-fashioned German professor: God is in heaven, and two-plus-two equals four, and evolution happened, and that’s it.” David also found Müller to be very intelligent, but “he was so utterly different from Chica that this animosity developed very early on.”

It didn’t help that the Gierer lab had been a fun, tight unit. Its members sometimes “went skiing together, had dinner together three times a week,” David said. And it was coming at developmental biology from fresh angles: Gierer, the physicist; Meinhardt, the theorist; David, the biophysicist; Bode, the molecular biologist; and Chica, the former linguist. Müller, on the other hand, was a classically trained biologist, doing science in what might have felt to them like the stodgy old way.

“We were in a completely different world, and it was pretty easy for us to develop a certain degree of contempt for Werner Müller as being kind of old-fashioned, slow-witted,” David told me. “None of this was actually true, but this image kind of developed.”

By the time the lab broke up, Schaller — Chica’s husband — had become a full professor and the head of the Institute of Microbiology at Heidelberg University. Chica, having finished her doctorate, took a position as group leader at the European Molecular Biology Laboratories in Heidelberg to remain close to him.

She continued to work with hydra, but the position at EMBL was only a five-year appointment, and by 1979, Chica again needed to find a new posting. Müller, meanwhile, had moved from his assistant professor position at the University of Tübingen to professor at the Technical University of Braunschweig, and then to full professor and Director of the Zoological Institute at the University of Heidelberg. Though Chica did not seem to admire him, he had space and welcomed her, possibly hoping her background in molecular biology would bring a fresh perspective to his department. She funded her work with grants.

Then, in 1981, Chica, working with the biochemist Heinz Bodenmüller, revealed the actual sequence for the peptide she had claimed was the head activator. It was produced by nerve cells, they wrote, stored in neurosecretory granules, and had the amino acid sequence of pGlu-Pro-Pro-Gly-Gly-Ser-Lys-Val-Ile-Leu-Phe.

The sequenced compound brought the head activator out of theory and into the physical world. Chica and Bodenmüller filed a patent on the head activator substance in Germany even before publishing their paper, following that with an application at the U.S. patent office. The compound, they claimed, was of interest as “a research substance and pharmaceutical composition,” and Chica had the Swiss company Bachem synthesize it, making it available for anyone to buy and experiment with.

Meanwhile, the parts of the Gierer-Meinhardt model were falling into place. Because Chica had sequenced the head activator, it seemed possible the other three substances — head inhibitor, foot activator, and inhibitor — would eventually be identified as well. That left proving that these substances existed in gradients along the hydra body, evidence for which was soon supplied by Harry MacWilliams, a Harvard University researcher.

MacWilliams focused on foot growth in hydra, and the Gierer lab in 1972 had invited him to visit. When he returned as a postdoc fellow, he used a grafting technique1 to show that foot and head activation acted on a gradient — meaning that activation for a head was “confined to the presumptive head zone” and something similar happened in the foot region with foot growth. This, MacWilliams wrote, was “consistent with a version of the Gierer-Meinhardt model.”

MacWilliams published two papers in 1983 detailing this work. Though other hydra morphogens had not yet been sequenced, the hydra community then had the head activator and the “Gierer-Meinhardt model, and … Harry MacWilliams’s grafting experiments,” Steele told me. “Those three things in aggregate cemented what seemed like a consistent story.”2

Does It Replicate?

Cracks began to emerge almost immediately, however, as other researchers struggled to replicate Chica’s findings.

Part of the difficulty might have been due to the demands of her initial experiment, which involved meticulously harvesting, grinding, and then centrifuging vast amounts of hydra. “It was very hard work,” David told me. “It’s amazing that she was able to get enough to generate a sequence, and then show that the synthetic head activator actually functions.”

The small quantities of hydra such work yielded were indeed an issue, which Chica got around by seeking out another raw material source. In their 1981 paper, Chica and Bodenmüller wrote that they isolated the head activator from the sea anemone Anthopleura elegantissima, which is larger than hydra, abundant, and contained a substance that “seemed to be identical to the head activator from hydra.”3

Switching out hydra for sea anemone may look a little like a “bait and switch,” Steele said, but it was reasonable to say “if it’s in one cnidarian, it’s in another.”

Regardless of how (and from what organism) the compound was isolated, testing its activity wasn’t particularly easy, either. Chica stressed that everything had to be done exactly so — the animals needed to be healthy, for instance, and the cutting done quickly — or it wouldn’t work.

That left the door open for criticism, which started even before the head activator substance was sequenced. At UC-Irvine, which had an active hydra community, developmental biologist Dick Campbell and colleagues were able to strip a hydra of all its interstitial cells, leaving the animal without nerve or nerve stem cells — the same cells in which the head activator substance was apparently made and released from. But even in this state, the hydra still exhibited polarity reversal, and the animal was “capable of essentially normal development,” the authors wrote in a 1978 paper Observing this work, Jonathan Slack, from the Imperial Cancer Research Fund in London, noted in Nature that it “seems that the significance of the head activating substance will now have to be reassessed.”

Yet it does not seem that Chica did so. Decades later, she would suggest that neurosecretory granules must form in the epithelial cells, rather than interstitial cells, and therefore lead to the development of the head activator.

Her explanation did not work for Steele, who interacted with Campbell at UC-Irvine and told me that Campbell had “very convincingly” shown that “nerve-free hydra can bud and regenerate heads.” Steele did “not buy” Chica’s argument that epithelial cells leap into the breach and produce head activator in hydras without nerves. “There is no obvious biological logic for that,” he told me. “Why would epithelial cells be able to take over a function that evolution has not prepared them for?”

Others were likewise questioning what they thought they had learned about hydra. Berking, who had worked in Chica’s lab at EMBL to isolate head and foot inhibition substances in hydra, wrote in Roux's Archives of Developmental Biologyin 1983 that these proposed substances were actually “an artefact” produced by the separation process. In fact, he wrote, substances could simply be found in Dowex 50 — a liquid used in chemistry analysis — that would also inhibit head regeneration. Berking added that “we have not been able to confirm that the extract from heads preferentially inhibits head regeneration and the extract from feet preferentially inhibits foot regeneration.”

Berking's comments might have ended their friendship. She published a reply within the year:

In a recent publication in this journal, it was claimed that the head inhibitor we isolated from hydra is a Dowex artefact, that a separate foot inhibitor does not exist in hydra and that the only inhibitor that has so far been isolated from hydra is one which inhibits head and foot regeneration equally well. These statements are incorrect and require a response.

Chica wrote that she had repeated Berking’s experiment and did not see the Dowex artefact, concluding, “I do not see any solid argument for not maintaining our present position that several chemically different inhibitors can be isolated from hydra with different specificities for head or foot formation.”

Bad Blood

By 1984, Chica was once again seeking a full professorship. The hydra community in Germany was small and tight, a group of researchers siloed by geography, all studying the same animal. They sat on review committees for each other’s proposals, and they saw each other at conferences.

All of that might naturally have bred competition, but the tension that had been bubbling between Chica and Müller since their Tübingen days grew after she set up in Müller’s department. The two groups sometimes had co-lab meetings, said Monika Hassel, a student in Berking’s lab around this time, and during them Chica often made “derogatory and snippy comments” that were “hard to stand.”

To make matters worse, Müller never believed in the head activator. And David told me that since Müller was convinced that the head activator didn’t exist, he thought anybody who credited it was foolish.

Sometime around 1984, Chica and her co-author, the hydra researcher Sabine Hoffmeister, sent out a paper concerning a biochemical marker for foot differentiation in hydra. The journal, Roux’s Archives of Developmental Biology, sent the paper for review to Müller, given his experience as a hydra researcher. Müller had a problem with a figure showing the concentration of head and foot inhibitors in parts of the hydra. When Chica saw his comments, she asked to have him removed as a reviewer, then redid the experiment herself.4 She turned in the new results to the editor, who published the paper.

Meanwhile, Chica applied for professorship positions in Karlsruhe and Regensburg, but didn’t get them. She turned down an offer in Bochum and also in Braunschweig; what she really wanted was a position in Heidelberg, which would keep her close to her husband. In 1988, an offer was finally on the table for a professorship in ZMBH (Center for Molecular Biology) at the University of Heidelberg. David wrote her a strong letter of support, calling her “one of Heidelberg's most distinguished scientists.”

Yet Chica did not get the position. The reason, from what I can gather, was Müller, who once told Hassel that, in his hands, the head activator “never worked” as described in Chica's publications, and because of this felt it was “not appropriate” for Chica to “become a professor in Heidelberg.”

And at some point during Chica’s review process for the Heidelberg professorship, David told me, there was “an attempt by [Müller] to prove that she had falsified her data.”

This accusation caused an explosion. The University Senate was called in. The subsequent inquest was conducted in English, not German, Hassel said, because English is more broadly understood in the scientific community. This decision benefited Chica, who had studied English and lived in the U.S. Müller, however, struggled to communicate as clearly in English. While this may have swung the senate in Chica’s favor, the underlying accusation of falsified data likely proved more important. David said he was asked to serve as one of the external referees and discern whether Chica had done so, but Müller’s accusation “simply wasn’t true,” he said.

In the end, the University Senate found for Chica. Müller, Hassel told me, was fined 40,000 Deutschmarks (~$22,760) — a damaging sum. “He had a young family, and he didn't have any money in the bank,” she said. “So it was terrible.”

It had all become “extremely ugly,” David told me. Müller had been shamed and fined, but the mess had somewhat tarred Chica, too. In the end, David said, “Chica had no choice. She couldn’t stay in Heidelberg,” and in 1991, she took a full professor position at the Institute for Molecular Neurobiology in Hamburg instead.

Moving On

By the ‘90s, interest in the head activator was waning. “So many people tried to repeat Chica’s experiments,” Berking said. “It was frustrating. A few effects were there, and if you tried again, it was no more. People lost patience to study the head activator.”

Science marched onward, and in the years following, new discoveries undermined the head activator. In 1997, a group of researchers in Japan, working with David, Bode, and Thomas Bosch, isolated 286 peptides from Hydra vulgaris (called Hydra magnipapillata at the time), and tentatively determined the amino acid sequences of 95 of them — none of which were the head activator. Because the group did not identify all peptides in hydra, it was possible that the head activator still lurked somewhere in the animal, but its absence from the data further damaged the credibility of Chica’s peptide.

Then, in 2000, a group of researchers published a paper suggesting that the Wnt-signaling pathway was behind head regeneration in hydra. The pathway appears across species, and includes a network of proteins that control cell differentiation and tissue and organ formation in embryonic development. The pathway molecules Wnt and Tcf are expressed in the top of the hydra, near the mouth and tentacles, and the authors, led by Thomas Holstein, wrote that the hydra Wnt signaling pathway was involved in “local self-activation in the hydra head organizer.”

The work was enough to convince David that “the Wnt-signaling pathway is the activator” in the Gierer-Meinhardt model for hydra head morphogenesis, he told me. It dealt another blow to Chica’s head activator, though it was still possible that the peptide she had championed was a component upstream of the Wnt pathway in hydra.

Conclusive evidence against the head activator emerged in 2010, however, when the hydra genome was sequenced at the J. Craig Venter Institute. The work was done by Venter, Steele, Bode, David, and 70 other researchers from around the world. The genome came from Hydra magnipapillata, and the authors estimated that “the hydra genome contains ~20,000 bona fide protein-coding genes.” But the “head activator peptide sequence is not encoded as such in the hydra genome sequence,” the authors wrote, noting that “the origin of the Head Activator peptide remains unresolved.”

The sequenced hydra genome was “the final nail in the coffin” for Chica’s head activator, Steele said. The peptide simply wasn’t encoded in the hydra genome, so whatever Chica had been experimenting with could not have come from the animal itself.

By then, Chica had mostly moved on, too. After taking the professorship in Hamburg, she opened a new chapter in her life, focusing on G Protein-Coupled Receptors, which are found on the surface of cells and respond to extracellular signals. She and Schaller also shifted their focus to philanthropy. Schaller had been a founding member of the biotech company Biogen in 1978, and by the 1990s, his shares had turned him into a millionaire. He and Chica reportedly put three million euros into The Chica and Heinz Schaller Foundation, which has funded basic biomedical research since 2000 and given out prize money to Heidelberg-based young scientists since 2005.

Schaller died on April 10, 2010, at 78, after a “short period of severe illness.” Chica herself was in her 70s by then and seemed to grow wistful. She began working on a book about her personal and professional life with Schaller. She found herself revisiting hydra and the head activator.

In October 2015, Chica emailed Steele to ask about a “multiheaded mutant” from the Chlorohydra viridissima strain, which had been created in 1961. Chica had worked with the mutant in the ‘70s and wanted to know what genomic analysis might reveal about the mutant’s head formation. Chica seemed to be asking Steele if he’d do the sequencing, he told me, but Steele “had absolutely zero interest” in throwing any money or time at the head activator.

Chica also told Steele that the head activator sequence was derived from a substance also found in sea anemone and rat intestine.5 The rat genome had been sequenced in 2004, and Chica admitted that the head activator “sequence is not present.”

“Conclusion: we must have a sequence error” in the original head activator sequence, she wrote. The methods they had used at the time were “crazy, adventurous,” and in the end, she felt “we were close, but not correct.”

Her book came out in 2016, a self-published autobiography, titled (translated): Chica and Heinz Schaller, Life and Science. She is listed as the author, though she also credits a journalist with helping her interview and write.

I ordered a copy and spent a few days using Google Translate to convert it to English. I hoped it would tell me more about who Chica was, and I also wanted to see if she mentioned Müller. I found that the book supplied, with great candor, deep backstories for both her and Schaller. The book revealed that Chica’s mother had gotten pregnant out of wedlock and that she wanted to abort the child, but her father had threatened suicide if she did. She wrote that Schaller used to distill alcohol in the lab and distribute it to his colleague, and that Chica had once been in love with Klaus herself.

It also shockingly revealed that Klaus and AnnMarie married, and that Klaus later killed AnnMarie, their two children, and himself. It disclosed that Schaller had some sort of affair, that Chica had left him for a time, and that Chica and Schaller tried to have children, but could not. It confessed that Chica had fallen in love with other men during her marriage, and finally, that Chica and Schaller had once grown marijuana in their garden.

These details — save for the murder-suicide of AnnMarie and her family — are not all that shocking. A little home-distilled alcohol, a little marijuana, the ups and downs of a very long and seemingly successful marriage, a failure to have children: these are the things that make up many normal lives. But to someone like Müller, conservative as he appeared to be, these details might have appeared scandalous, as was her choice to publish them.

Her book also includes the history of her hydra work and her failed pursuit of a position in Heidelberg, though it does not mention the ugly university senate hearing. Müller is barely mentioned, except, notably, earlier in the narrative, when she is remembering her ascent in the developmental biology field. She writes: “Chica’s successes bring her not only invitations and an unfaithful husband, but also hostility. The latter escalates to accusations of fraud. They come from Werner Müller’s chair.”

That’s it, the only glimpse at what happened between the two of them in Heidelberg from her perspective.

Werner the Writer

Müller also turned toward writing as he aged. He published a book based on his life in 2021, roughly translated as Self-liberation from the Shackles of Church Religion, that provides insight into his background. Written under the nom de plume Frank Beiderbeck (the author biography notes that Frank Beiderbeck is actually “a professor emeritus at the University of Heidelberg” who has the real name “W.A.M.”), the book’s plot centers around Müller’s brother, who died young of leukemia.6

It is in his second book, published in January 2022, that Müller turned to the story that had been on his mind for decades. Entitled: The Price of Research, the book appears under the same pen name, Frank Beiderbeck, and contains what can be described as a crime story based on true events from a university institute in Heidelberg. The book’s biography likewise says the author was a professor of biological sciences at the University of Heidelberg and names his other books, including the “Self Liberation” book about Paul, directing readers to Müller’s Wikipedia page for more information.

What follows, if read as crime fiction, is poorly written. Character motivation is unclear, violence arrives out of nowhere, and the book has a confused chronology. But read as thinly veiled history — as it’s clearly meant to be — it’s fascinating.

Müller begins by writing that it should not be “too difficult for those interested to find out the real names of the protagonists of this story, especially since several known personalities, who were not entangled in the affair, are mentioned without pseudonyms.” Indeed, the name Alfred Gierer appears in the pages, as does Hans Meinhardt.

The book is narrated by a fictional journalist, telling the story of the university professor Michael Walter — an avatar for Müller. Amidst poisonings from lab-distilled alcohol and homegrown marijuana (echoes from Chica’s book), and copied laboratory protocols and the dead bodies that prop up the crime thriller plot, Walter is served with a letter “from the Ministry of State,” in which “a ministerial director announced that a disciplinary enquiry has been opened against him.” Walter is threatened with the loss of his position without benefits, and a fine of 40,000 euros, unless he declares in writing to “never again to remark publicly that Frau Dr Franziska Jansen had exhibited scientific misconduct and presumably committed fraud.”

Franziska Jansen, of course, is meant to be Chica.

The novel also tackles what transpired over the years for Gierer and Meinhardt, using their actual names, and also Jansen and various colleagues working on the activators and inhibitors of hydra generation. The book mounts a lengthy attack on the veracity of the head activator, using figures from Müller’s own work. There are chapters dedicated to nerve growth factors and the organizer discovery by Hans Spemann. There is a discussion of the Wnt pathway and a section where Michael Walter uses the head activator “synthetic product” bought from Bachem, and it “had absolutely no effect on his own animals.”

It also includes a description of Walter being asked to review a paper by Jansen; he criticizes the conclusion, and when the paper is resubmitted, the conclusion is not changed. The book includes scenes of an official hearing before a Senate, conducted in English, during which Walter struggles to communicate. Jansen (a “former translator”) has no problem.

The book is Müller’s version of the entire head activator story, protected behind a curtain of fiction. Near its end, Müller declares that “the truth had to be worked out in the laboratories of the world.”

Perhaps this has been done for Chica’s head activator. Steele told me he recently went to a hydra meeting in Germany. Not a single talk or poster at the gathering mentioned Chica’s peptide, he said. Head activation in hydra is still discussed in the community, but now in the context of the Wnt pathway. Science has shown that Chica’s head activator “is not encoded by a gene in a standard manner in hydra. That is clear, if it’s just not in the genome,” Steele said. So if Chica’s substance is somehow made in hydra, “it’s produced by some non-canonical method that I have a hard time conceiving of.”

However, this leaves open the question of what was really sequenced by Bodenmüller in the 1981 paper. It’s possible the substance came from bacteria that somehow contaminated Chica’s experiment. Perhaps that’s why the head activator was also found in mammals. But “it’s clearly not in anything that’s in GenBank, so it’s not in some common bacterium that contaminates lots of things,” Steele said.

Regardless, Steele knew Bodenmüller to be a careful protein biochemist who was “not just making this stuff up.” Steele said. The sample he used had proteinaceous material in it, and they got a sequence.

“That's the real puzzle to me,” Steele said. “How did they get that, or what it was that they sequenced, where it originated? And what organism makes it? It leaves you at the end with a feeling of … Is this something that’s ever going to make sense?”

At War and Peace

I once interviewed the great Eve Marder, a National Medal of Science winner and professor of Neuroscience at Brandeis University. She’s in her 70s now, but told me that when she was coming up in science in the late 1960s and ‘70s, she was often the only woman in a room full of men. She realized there were two ways women could handle this disparity. One was to be unfailingly polite, a lady at all times. The other, she said, was to constantly assert yourself and be combative. If you didn’t do that, you simply would not be heard.

It is difficult not to interpret Chica’s behavior accordingly. She came up in science when there weren’t many other women around. She’d been one of three girls in her high school class, among 30 boys. She’d followed Schaller around, the wife to his scientist, until she got a PhD herself. And she was the only woman in the Gierer lab.

That may have had something to do with Chica often being described as angry, dismissive of others, or unpleasant. She constantly had to kick down doors just to be in the room, and then had to raise her voice to be heard. Her biography includes passages aimed at the sexism she felt she’d endured, and she helped set up the Chica and Heinz Schaller Foundation in part to support young female scientists.

Steele met Chica in person just once or twice, but he confirmed this. “She was a woman fighting for space in the biological research sphere at a time when women in Germany were not taken very seriously in academics,” he told me. Yet as a young doctoral student in a lab full of more accomplished men, she’d performed a tedious, intensive experiment to isolate a substance that — in the moment — seemed to build a bridge between the worlds of developmental biology and modern molecular biology.

This is undoubtedly part of her story. The other part, however, remains her scientific legacy itself: her work on the head activator vexed many people in the field. I went looking for Cok Grimmelikhuijzen, the Dutchman who had been Chica’s postdoc. After failing to reach him, I finally emailed Frank Hauser, who had published papers with Cok. He told me Cok passed away in 2024, but Hauser remembered Cok calling the head activator an “unscientific fabrication.” Perhaps Cok had been “overly critical,” Hauser said, but those were his words.

Then there is Doug Fisher. He worked under Bode at UC-Irvine, and he did “everything one could imagine doing” to clone the head activator, he said, “and nothing worked.” The group at Irvine had a journal club that would discuss papers. Every so often, they’d read a paper that confused them, one where they didn’t understand the design, the controls, or the results, and then “everything would grind to a halt,” he told me. This happened enough times with papers from Chica’s group that Fisher began not to “believe anything that came from her lab” during that time.

That leaves Müller, her fiercest critic — should we believe him? Steele knew Müller, too, and once had dinner at his house. This was in 1993, when both were attending a hydra conference in Günzburg, Germany. Afterward, Steele and a couple of colleagues headed to Heidelberg. Müller drove them there and invited the group — along with Monical Hassel — over for dinner. Müller’s wife joined them, and the group had a “carefully orchestrated meal,” Steele said, of Zwiebelkuchen and Federweißer: onion cake and young wine from the fall harvest. The night was enjoyable, if “a little bit stilted.”

It’s possible that Müller simply disliked Chica and wanted to hurt her career. But it’s also possible that he was a quiet, somewhat stiff person who had replaced religious dogma with research. And because of this, perhaps he felt he had to stand up for the purity of science.7

Berking told me that Müller “was hurt by [Chica],” and “tried to digest” their horrid interaction for years. “Eventually, he wrote this book for himself,” Berking said. “It was for him to write down his side of the history.”

Berking told me Müller didn’t show him the book until sometime after he had self-published it. “That was strange for me, that he gave it to me not immediately,” Berking said. “I was involved, too, in this problem.”

It’s that image, more than any other, that sums up the great drama of the head activator for me. More than 30 years after the head activator made its scientific splash, decades after Müller had been called in front of the university senate, and more than fifteen years post-retirement from Heidelberg, he was still thinking about it. Müller, writing up his story even after Chica’s death and not all that far from his own, in September 2022. Müller, handing this thinly veiled fiction over to Berking as if to say:

“Remember what happened back then, with the hydra? I want you to read this.”

{{divider}}

Correction: A prior version of this article stated that Stefan Berking was a student in Chica Schaller’s laboratory. We have corrected this error.

Brady Huggett is the features editor at The Transmitter, and a contributing editor at Asimov Press. He is also the writer and producer of the limited series podcast, Hope Lies in Dreams.

Thank you to Andrea Weaver for translating The Price of Research book, and Nicholas Huggett for help with additional German-to-English translations. The header image was made by Ella Watkins-Dulaney.

Cite: Huggett, B. “Mystery of the Head Activator.” Asimov Press (2026). DOI: 10.62211/28kw-72nq

Further Reading:

- Chica und Heinz Schaller — Leben und Wissenschaft. By Chica Schaller. Copyright 2016, Chica Schaller.

- Hydra and the birth of Experimental Biology — 1744. Abraham Trembley’s memoirs concerning the natural history of a type of freshwater polyp with arms shaped like horns. Sylvia G. Lenhoff and Howard M. Lenhoff. Copyright 1986 by the Boxwood Press.

- Selbst-Befreiung aus den Fessein der kirchlichen Religion. Erzählung. Frank Beiderbeck. Copyright NOEL-Verlag.

Footnotes

- This involved inserting bits of hydra into other hydra and monitoring their growth.

- The two papers of MacWilliams, who passed away in 2011, are still considered “landmarks” in developmental biology, Steele said. And the Gierer-Meinhardt model is still a valid theory for morphogenesis. Only the head activator compound came under fire.

- The U.S. patent also calls for beginning with chopped pieces of the cnidarian Anthopleura elegantissima.

- Source: Chica’s biography.

- Work on both organisms had been done in parallel. In 1974, she published that the rat brain contains a “peptide with similar or identical biological and chemical properties as the head activator from the hydra.” In 1981, she published that the head activator peptide sequence was isolated from the human hypothalamus, bovine hypothalamus, and rat intestine.

- I ordered this book too, and translated it, hoping it would tell me more about Müller’s background. It reveals that Müller and his brother were born into a large, devoutly Catholic family living in a small railway guard’s house. The boys shared a bed, and sometimes went barefoot in the summer to preserve their shoes for winter. His brother went to a Catholic boarding school and then into a monastery before throwing off religion and discovering science. It is possible that Müller went through a similar spiritual journey on his way to a life in the lab. Either way, his childhood can be starkly contrasted against Chica’s more bourgeois early life. Perhaps a fact that added an extra layer of animosity.

- I’m also struck by the size of his fine: 40,000 deutschmarks would be valued at about $125,000 today — a fine I certainly could not pay.

Always free. No ads. Richly storied.

Always free. No ads. Richly storied.

Always free. No ads. Richly storied.